The rise of Angkor and the Khmer Empire

At the time of Jayavarman II’s return, Chenla was under the control of the Shailendra, a dynasty of foreign kings from Java.

Chenla or Zhenla is the name used by scholars who study Cambodian history to describe the political state that preceded the Khmer Empire. There is debate whether Chenla was a unified kingdom or a loose alliance of separate states.

In 781, Jayavarman II declared the independence of Chenla from the Shailendra kings. He swiftly built a power and support base by conquering and uniting the patchwork of petty kingdoms and domains in Chenla.

By 790, he had declared himself king of Kambuja. Jayavarman II continued his consolidation of the region through military conquest and political negotiations.

There is debate amongst scholars who study the history of Cambodia around the translation of ‘Java’ in relation to Jayavarman II’s exile.

A translation from the Sdok Kok Thom temple (now located in modern-day Thailand) states that ‘His Majesty came from Java in order to rule in Indrapura’; however, the distance from Indrapura to Central Java in Indonesia is vast.

This has caused some scholars to suggest that ‘Java’ may refer to some part of the Malay Peninsula or Sumatra, while others even suggest ‘Java’ is a mistranslation and Jayavarman II’s exile was to the east of Angkor among the Cham.

Regardless of where ‘Java’ was, what is agreed is that it was an aggressive power from which Jayavarman II was determined to free his country.

An inscription from the temple at Sdok Kok Thom recounts the story of a ritual that occurred in 802 on top of the sacred mountain Mahendraparvata.

In this ceremony, Jayavarman II was proclaimed a chakravartin, Lord of the Universe, and took on the title devaraja, God-king. His successors would continue to use these titles and draw on them to cement their power and authority as absolute rulers ordained by the gods. Jayavarman II’s ascension as devaraja marks the beginning of the Khmer Empire.

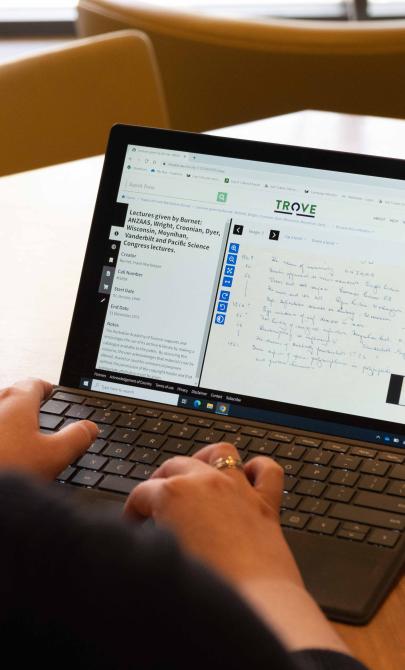

Yves Coffin, [Angkor Wat, royal parade reliefs, officer on elephant, stone carvings], nla.gov.au/nla.obj-140370956

Yves Coffin, [Angkor Wat, royal parade reliefs, officer on elephant, stone carvings], nla.gov.au/nla.obj-140370956

For part of his reign, Jayavarman II ruled from the city of Hariharalaya. It was here that he died in 835. The city grew under the reign of one of Jayavarman II’s successors, Indravarman I (877–886). The new king shaped the city and built great temples and palaces in an extensive building campaign. He was also responsible for the first of the characteristic hydrological works that are synonymous with Khmer cities and temple complexes. More information about the hydrological works of the Khmer Empire can be found in the ‘Building Angkor’ module

Sometime between 889 and 900, Indravarman I’s son and successor, Yasovarman I, moved the capital city of the Khmer Empire from Hariharalaya to the plains around 20 kilometres to the north-west. He founded a new city and named it Yasodharapura (the City that MaintainsGlory); the city is also known as Angkor (Capital City). The new capital was linked to the old capital by a causeway. Yasovarman finished the construction of a large reservoir, known as the Eastern Baray.

The city of Angkor was both the empire’s political capital and the centre of spiritual and cultural power. The city was located an equal distance from the great lake of Tonlé Sap and the mountains, and had easy access to flat fertile land which supported the growing population with food. Angkor would become a powerful city that, according to recent research and archaeological exploration, may have sustained upwards of one million inhabitants at its peak. The city, except for a few episodes, would be the capital of the Khmer Empire until end of the Angkor period in 1431.

The Angkorian kings proved themselves to be skilled builders and politicians. They built grand monuments to the gods, their ancestors and themselves. This ambitious building program, together with the cult of the devaraja that surrounded the king, helped to cement in the minds of the population that the king was irreproachable in his rule and that his word was law.

Despite their divine status, Angkorian kings still had to pay for their building projects and general administration of the kingdom. There is debate among those who study the history of the Khmer Empire over how each king paid for and built the temples and palaces of Angkor and the surrounding regions. It is generally agreed that as supreme ruler, the kings of Angkor could levy taxes and manpower, both for construction and military service, as they saw fit or had need. The administration of the kingdom was reformed several times by different monarchs.

This helped them to better extract taxes and service from the population, especially those distant from the capital. In some administrations, provincial officers were given increased power and responsibilities to ensure the king’s will was followed and dues were paid. In others, the role of the provincial officials was reduced, and a more centralised approach was taken.

The Khmer Empire did not use a currency-based system. As such, taxes were typically paid in goods, predominantly rice, but often oil and cloth.

In creating a new administration, the king was able to not only better regulate the inflow of wealth, but he could use it to political advantage by conferring high-ranking positions, such as the Chief of Elephants, and coveted status symbols, such as the White Parasol, on those close to him or with whom he needed to gain favour.

Similarly, he could strip titles and land from those seen as being disloyal, strengthening his position.

Yves Coffin, [Bayon, Angkor Wat, reliefs outer gallery, stone carvings], nla.gov.au/nla.obj-140371101

Yves Coffin, [Bayon, Angkor Wat, reliefs outer gallery, stone carvings], nla.gov.au/nla.obj-140371101

Learning activities

- Many cultures have an origin story or legend describing their creation or beginning. Some describe the creation of the Earth or the people, while others describe how a people or individual established the nation. Why do you think these stories are prevalent in almost every culture or country? Consider the role these stories play in forming a national identity.

- Cities and large settlements thrive in a range of locations around the world. What conditions are required to sustain a large and successful city? Compile a list of things people and cities need to survive. Students should be thinking of things like food availability/area for cultivation, fresh water, raw resources, ease of connection to other places, ease of defence etc. Using an atlas or online map service, find a location that meets your criteria. Plan a tenth century city.

- Jayavarman II declared himself devaraja, God-king. Discuss how this title would have helped Jayavarman II and his successors to better rule the Empire. What image comes to mind when you hear the title God-king? Research the concept of the Imperial Cult and see if other societies have claimed their rulers to be divine.