Life under the Shoguns

Life during the era of the shoguns in Japan was highly structured and class-based, with clear divisions between social classes based on economic or political roles. This system was structured into 3 main classes:

- The ruling elite

- The warrior classes

- The peasant classes

In this feudal society, each class provided loyalty to those above them in return for protection, food, and work rights.

Understanding life under the shoguns provides insight into the complexities of Japanese society during this era. The relationships between various classes, the political structure, and the historical context reveal a nuanced picture of feudal Japan, where loyalty and social hierarchy played crucial roles in everyday life.

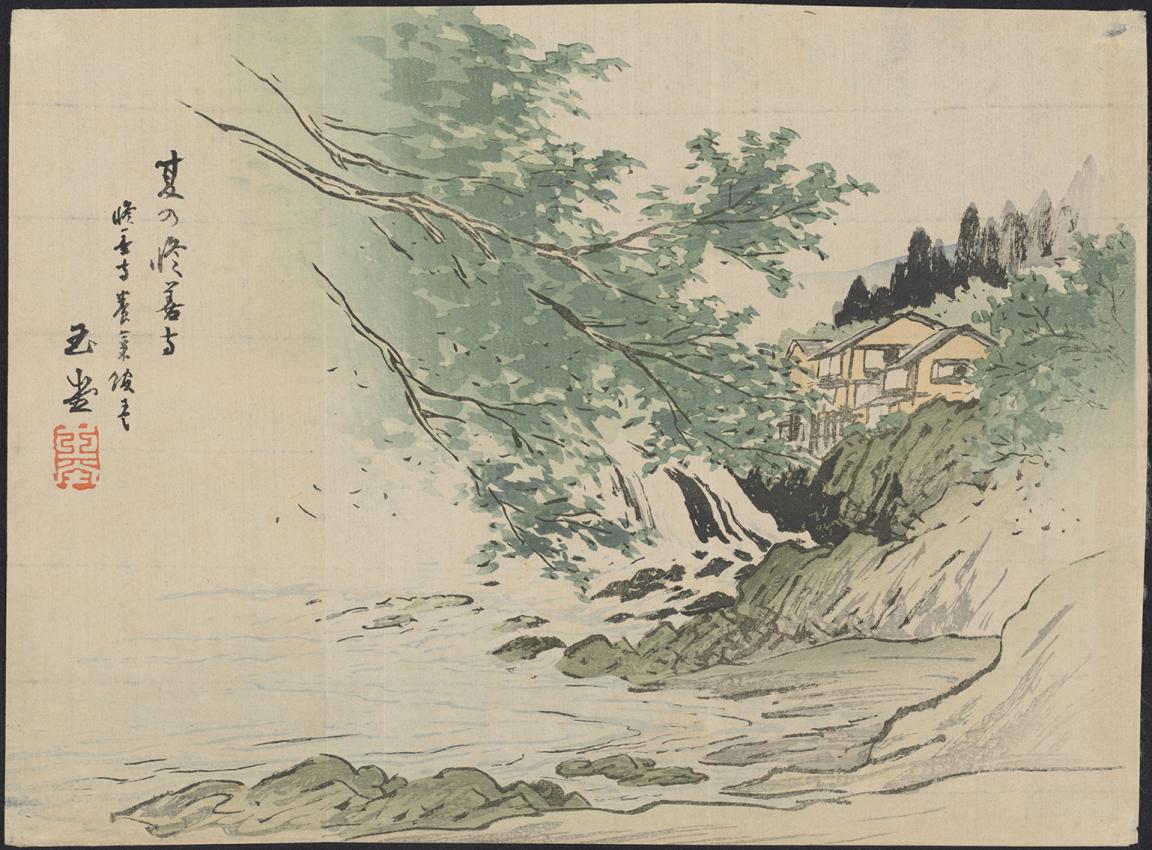

Gyokudō Kawai and 川合玉堂, Seiryū Hakubunkan, Tōkyō, 1908, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-152432945

Gyokudō Kawai and 川合玉堂, Seiryū Hakubunkan, Tōkyō, 1908, nla.gov.au/nla.obj-152432945

Peasant classes

Making up around 90% of the population, the peasant class had a challenging existence, focused on daily survival, paying taxes, and coping with frequent social unrest. This class was further divided by specific roles.

Primary producers

- Farmers and Fishermen: Held the highest rank within the peasant class as they were essential to Japan’s economy, supplying food like rice and fish and resources like timber for construction.

Artisans

- Craftspeople: Artisans were skilled in creating everyday items and tools, as well as items used in warfare. Some artisans became famous for their expertise, such as sword makers and potters.

Merchants

- Traders: Positioned at the lowest rank, merchants were often viewed negatively for making a profit without producing anything themselves. Despite this, markets became vital to communities, offering income to local authorities through taxes.

Hinin – "Non-people"

- A class considered "outside" society, the hinin (非人, "non-people") or eta (穢多, "filthy ones") performed jobs seen as impure or undesirable. They worked as actors, butchers, tanners, undertakers, and fertiliser collectors—roles essential but viewed as unclean.

Activity 1: Life in a class of society

Have the students research a class of Japanese society in the Kamakura, Ashikaga or Tokugawa Shogunates.

- What was life like for these people?

- Who did they pay their taxes to?

- Could they move up in society?

- Could they move down?

- What was their life expectancy and diet like?

Have the students compose a creative writing piece about a fictional person from that level of society. Encourage the students to use some Japanese terminology throughout their story.

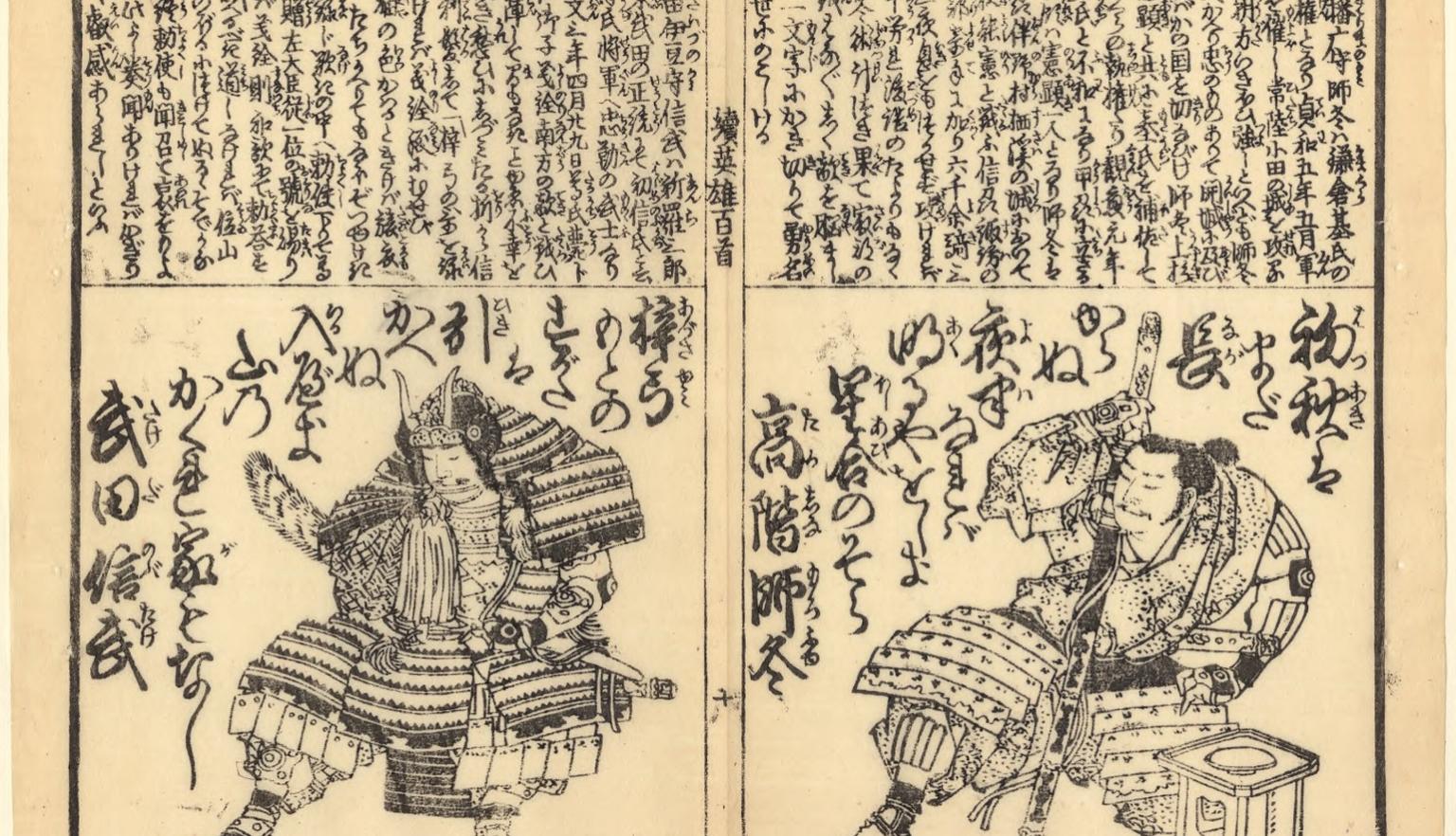

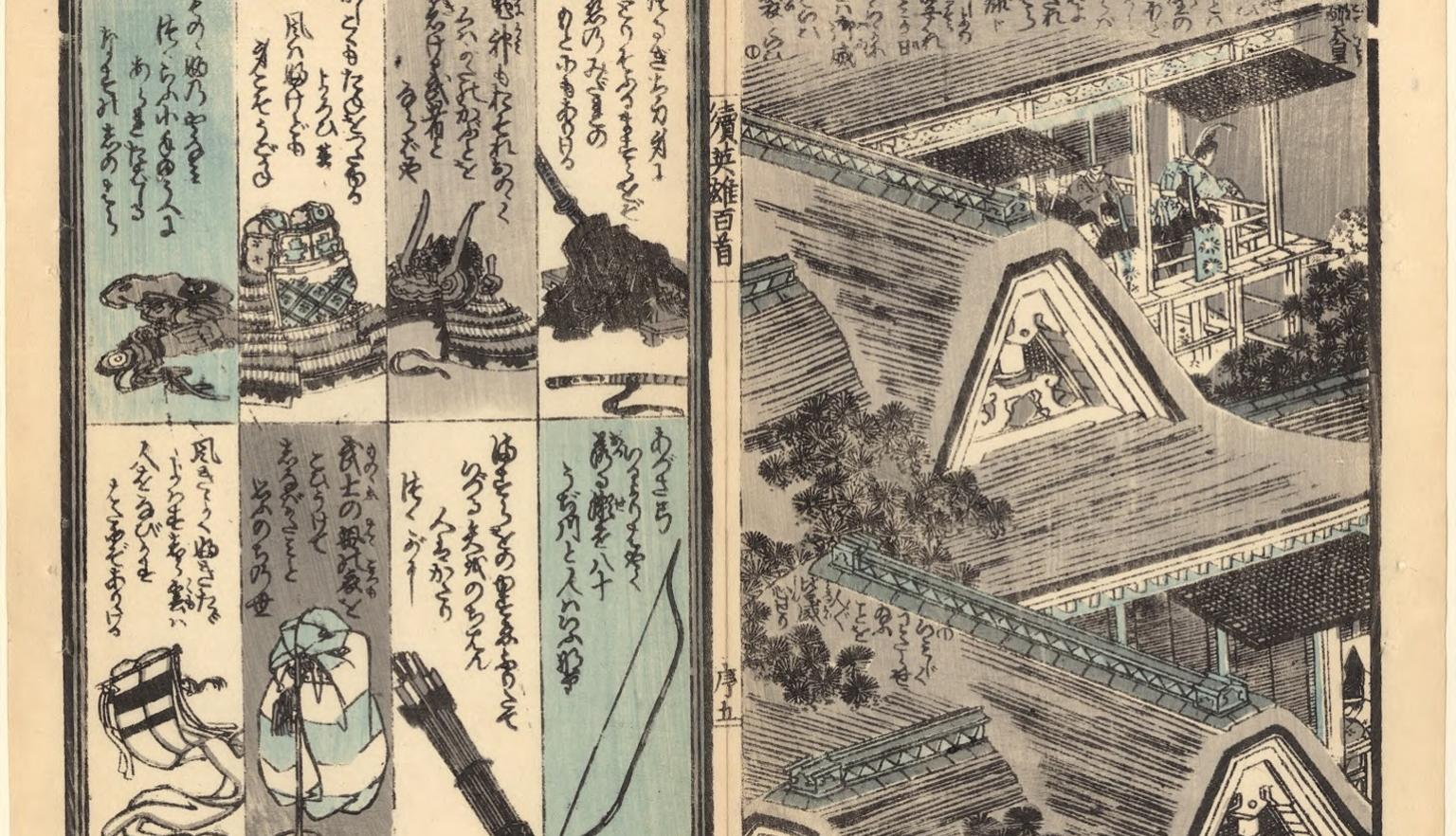

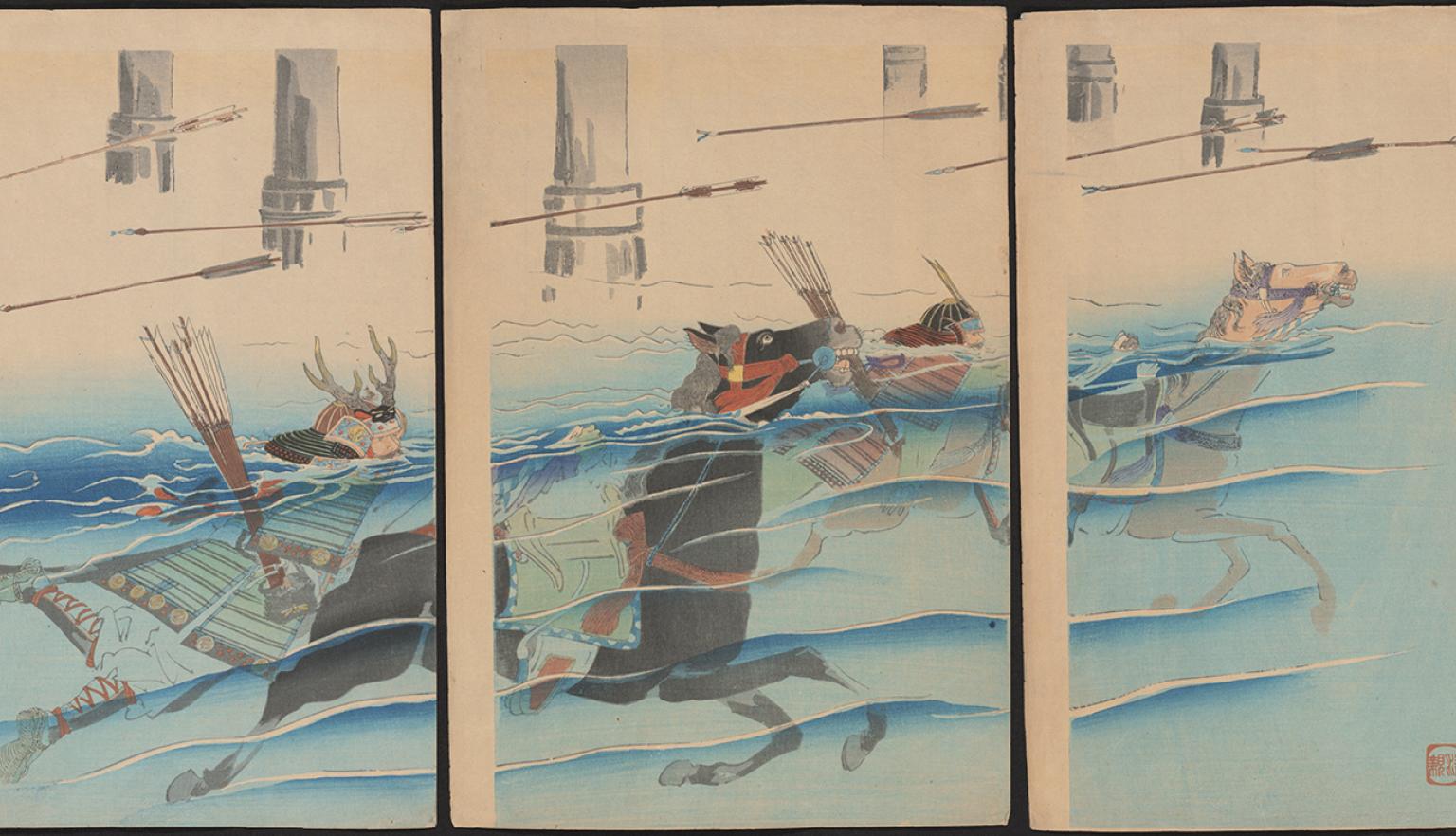

Warrior classes

Above the peasant class was the warrior class, consisting of Japan's military force from foot soldiers to high-ranking warlords.

Soldiers

- Foot Soldiers (Ashigaru): Drawn from the peasant class, they made up the bulk of the military, with archers, riflemen, and artillery units later added. They received wages from their daimyo (local warlord).

Ronin

- Masterless Samurai: Ronin were samurai without a lord. With no master to serve, they often sought work as mercenaries or bodyguards, sometimes turning to activities like gambling and extortion for survival.

Samurai

- Elite Warriors: Samurai were loyal warriors serving a master and held higher status than the ronin. Samurai received land or wages and often commanded military forces. Over time, many samurai became involved in political and administrative roles, although they maintained warrior traditions.

Daimyo

- Regional Warlords: Powerful hereditary leaders called daimyo ruled over large areas (han, 藩). Although technically under the shogun’s authority, daimyos managed their territories independently, controlling taxes, infrastructure, and military forces.

Activity 2: Inter-class relationships

Ask students to compare the relationship between the emperor and the shoguns to a modern constitutional monarchy. What are the differences and similarities?

The ruling elite

Shoguns

The shogun (Sei-i Taishōgun, 征夷大将軍) was the supreme military and political leader of Japan, ruling for nearly 700 years. While the emperor remained the nominal ruler, the shoguns held actual power. By claiming their authority stemmed from the emperor, shoguns legitimised their rule. This role was not elected; succession typically passed within families.

The Emperor

At the top of the social order was the emperor, a hereditary position with limited power under the shoguns, focusing mainly on religious and ceremonial duties. The emperor's influence in politics varied over time and peaked only after the Boshin War in 1868–1869, when the emperor was restored to full authority.