Freedoms and rights

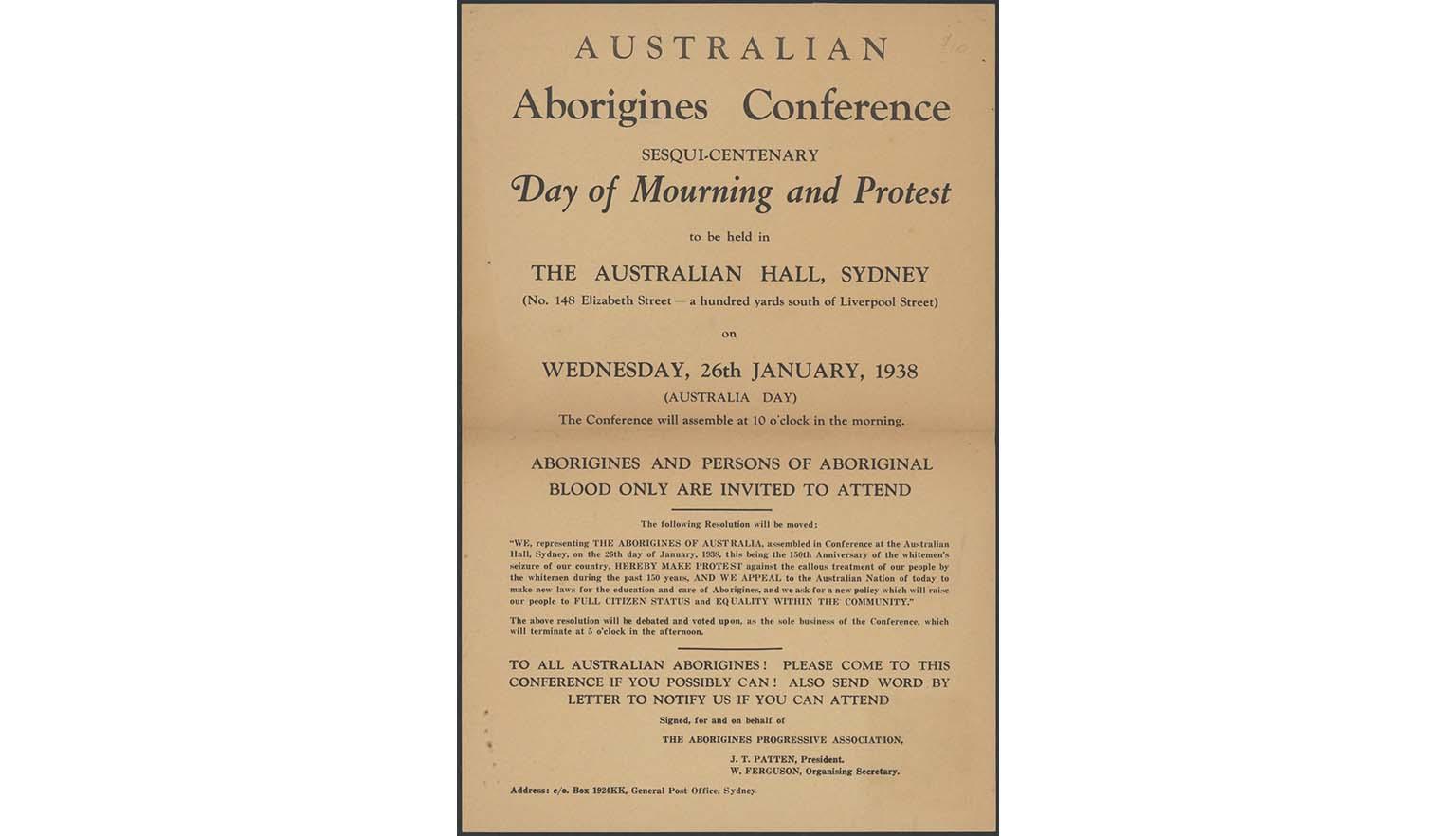

Since the Second World War, a growing need for international regulations regarding protections of human rights became apparent, leading to the establishment of intergovernmental organisations, such as the United Nations (UN), to promote global cooperation.

Freedom of opinion and expression:

The right to freedom of expression extends to any medium, including written and oral communications, the media, public protest, broadcasting, artistic works and commercial advertising. The right is not absolute. It carries with it special responsibilities, and may be restricted on several grounds. For example, restrictions could relate to filtering access to certain internet sites, the urging of violence or the classification of artistic material.

Freedom of association:

The right to freedom of association protects the right to form and join associations to pursue common goals.

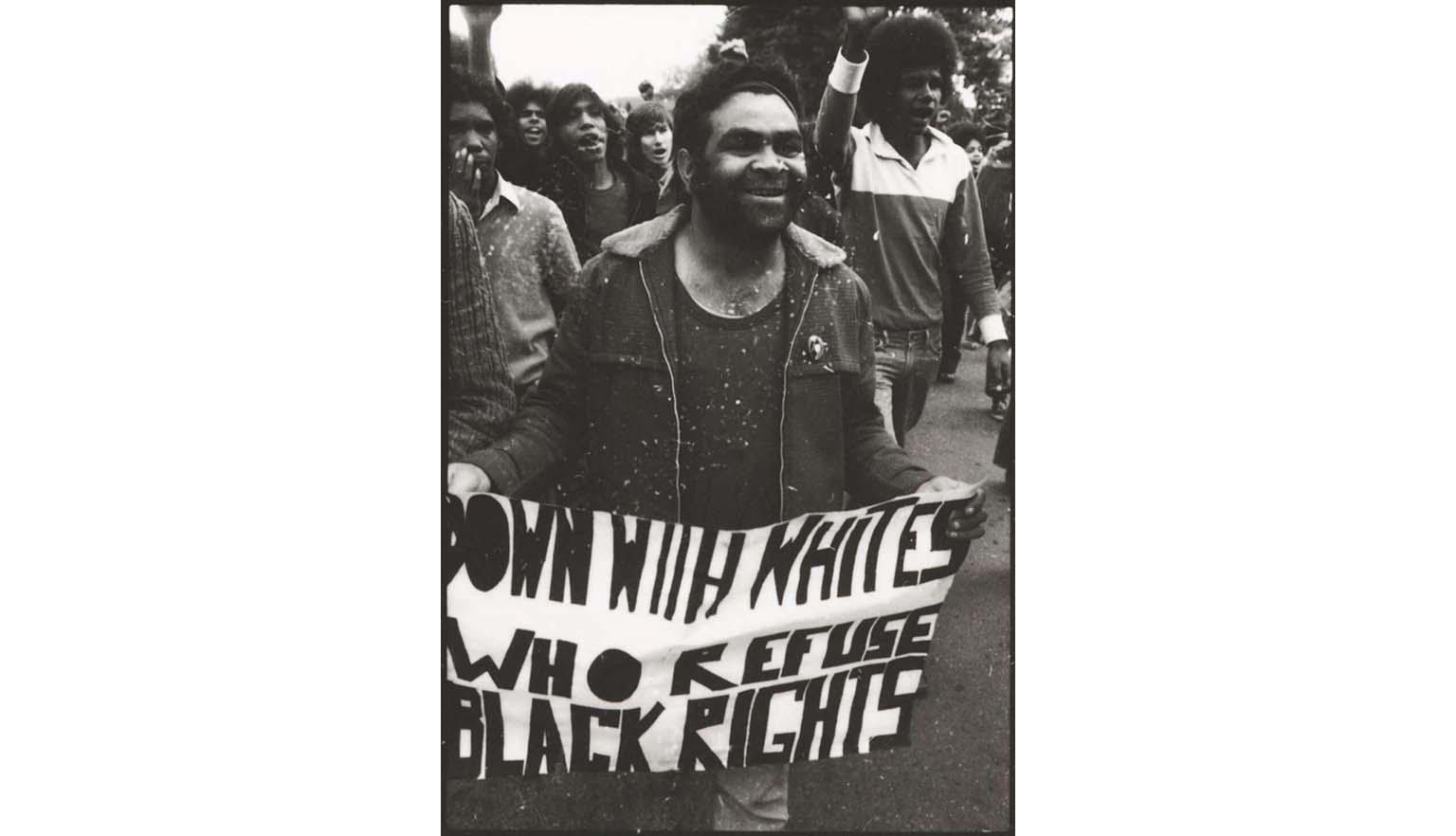

Freedom of assembly:

The right to peaceful assembly protects the right of individuals and groups to meet and to engage in peaceful protest.

Freedom of thought, conscience and religion or belief:

All persons have the right to think freely, and to entertain ideas and hold positions based on conscientious or religious or other beliefs. Subject to certain limitations, persons also have the right to demonstrate or manifest religious or other beliefs, by way of worship, observance, practice and teaching. Legislation, policies and programs must respect the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion or belief, unless they clearly fall within one of the permissible limitations discussed below.

Freedom of movement:

The right to freedom of movement includes the right to move freely within a country for those who are lawfully within the country, the right to leave any country and the right to enter a country of which you are a citizen. The right may be restricted in certain circumstances.

These definitions, set by the Australian Government Attorney-General’s Department, show how active participation in Australia’s democracy is encouraged. You can also see some of these definitions express limitations on these freedoms and rights; many of these rights are not absolute. Restrictions on forms of protest are an example of such limitations; these definitions include peaceful protests as being allowed, but no mention beyond this.

One fundamental UN treaty that relates to this resource is the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (1966), which aims to promote equal civil and political rights for all, including freedoms of speech, assembly and electoral rights. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights also relates to this module, but as it is a declaration it is not bound by international law in the same way treaties, conventions, protocols and covenants might be.

However, even when the Australian Government agrees to international treaties, this does not mean the treaties are immediately incorporated into Australian law. New domestic legislation is not always established for ratified treaties, if an assessment shows these treaty commitments are already covered under the current legal system. Therefore, it is possible that freedoms and rights established in treaties will not be translated into domestic law exactly as outlined in the treaty.

For example, Australia is the only Western democracy without an established ‘Bill of Rights’ document, which means many basic rights are unprotected. Of the rights that have been legislated, many are mentioned inconsistently in common law, Acts of Parliament or the Constitution. The problem with only brief mentions in legislation is that these freedoms can be hard to justify, and the lawfulness of these freedoms can be open to interpretation. This was the case when determining the legal freedom of ‘political communication’. On multiple occasions, the High Court of Australia ruled that the Australian Constitution holds an implied freedom of political communication, in order to allow for a true representative democracy.

Learning activities

- Think of some cases in Australia where freedoms of speech, association, assembly, religion, or movement have come into conflict with Australian law. What happened in each instance?

- Ask your students to create their own Bill of Rights. They should draw inspiration from existing human rights documents (such as the United States Bill of Rights, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights or France’s Declaration of the Rights of the Man and the Citizen (PDF, 134KB)), or include other rights that these past documents have left out.