Dear Mutzi: Writing a life through letters, memories and imagination

Dear Mutzi is a story that has been with me for a long time. It came from a curiosity I had about my grandfather Harry, where he came from and how his early life shaped the man he was.

Harry (who was then Hermann Pollnow), known by his parents as Mutzi, c. 1923

Harry (who was then Hermann Pollnow), known by his parents as Mutzi, c. 1923

It also came from a deep yearning I felt to know my great-grandparents Max and Edith Pollnow, who perished during the Holocaust. Max was a prominent Berlin surgeon who served on the Western Front during the First World War and received an Iron Cross medal for this service. Edith worked as a nurse during the war, but gradually became incapacitated by an auto-immune disease and pernicious anemia. Whenever Harry spoke of his mother, it was about her illness, about how she never left bed. But I always knew there was much more to their story than the patchy recollections Harry occasionally revealed.

Left to right: Edith Pollnow, Heinz Veit-Simon (Harry’s uncle), Max Pollnow, Irmgard Veit-Simon (Harry’s aunt), undated

Left to right: Edith Pollnow, Heinz Veit-Simon (Harry’s uncle), Max Pollnow, Irmgard Veit-Simon (Harry’s aunt), undated

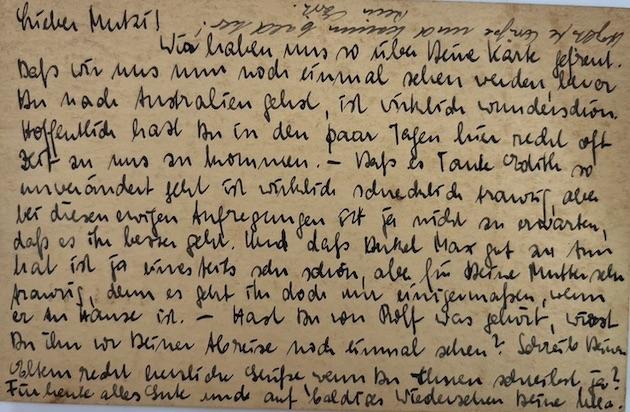

I knew little more than a few scant facts about Max and Edith until the day I found a box of their letters written to their son, my grandfather, who was known to his parents as Mutzi. This discovery was one I’ll never forget. They were hidden in plain sight, in a box in my mother’s study. I remember my heart racing as I scanned the wisp-thin papers, some type-written, some hand-written, all stained and weakened by time and, crucially, all written in German. I knew these letters contained important information—all written between 1938 and 1940—but I was yet to find out just how significant they would be. The process of translation was arduous, as many were written in an old German script, and many almost indecipherable because of damage to the paper and the faded ink.

Letter addressed to Mutzi (undated)

Letter addressed to Mutzi (undated)

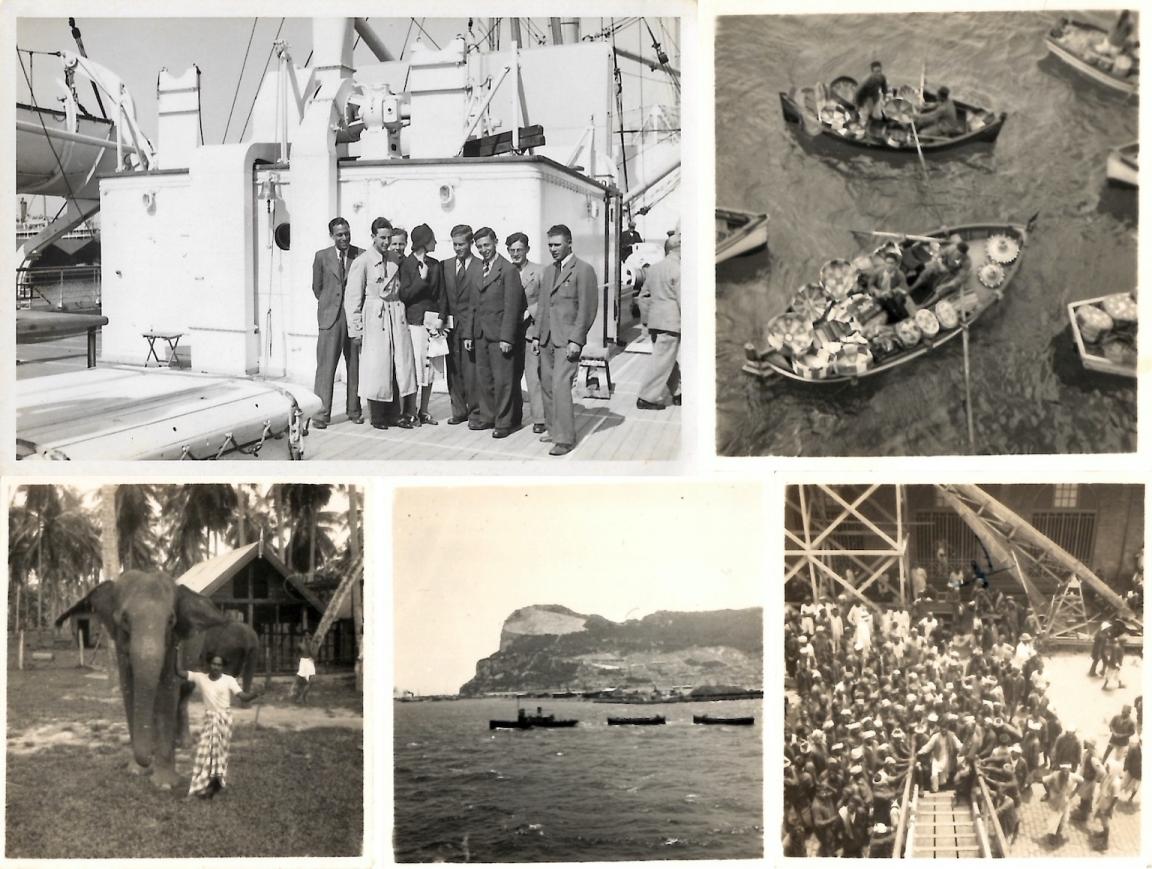

Each batch of new translations was a revelation, particularly the letters that were sent by Max and Edith to Harry during his emigration journey on board the S.S Strathallan. This was mid-1939, when the world was on the cusp of war. The insight into what daily life was like in Berlin during this time for Max and Edith was invaluable to the story, as were the photographs 18-year-old Harry took on his journey. He kept these photos close all his life, in a palm-sized brown leather picture album. When I first laid eyes on them my pulse quickened. The cliffs of Gibraltar; the cobblestoned alleys of Marseilles; the bustling port of Mumbai (then Bombay); elephants beneath the tall spindly palms of Sri Lanka (then Ceylon). What must an 18-year-old teen from Berlin have been thinking and feeling on this spectacular world tour, all the while knowing the perils he’d so narrowly escaped and the unknown fate of his parents?

Merchants at the wharf in Tangier, 1939; Crowd at the port of Mumbai (then Bombay), 1939; A Sri Lankan woman with elephant, 1939; The cliffs of Gibraltar, 1939; Harry (far right) and fellow migrants on board the S.S Strathallan, 1939

Merchants at the wharf in Tangier, 1939; Crowd at the port of Mumbai (then Bombay), 1939; A Sri Lankan woman with elephant, 1939; The cliffs of Gibraltar, 1939; Harry (far right) and fellow migrants on board the S.S Strathallan, 1939

When I undertook research in the National Library special collections, it became clear to me that Harry’s experience was shared by many migrants who fled persecution and found themselves in Australia. The Hay Internment Camp papers were particularly enlightening, as was the incredible ephemera about refugee and migrant employment schemes, of which Harry was a part. I even found a map of Kuitpo Colony, where Harry was first employed as a lumberjack in the Adelaide Hills.

Harry was a different man to many different people. To me he was an old man, doting and quick-witted, who for most of my childhood years gave me a pickle jar full of silver coins for my birthday, who wore his Canon DSLR around his neck at every family get together and was always interested in knowing about my life, even if he couldn’t quite remember who I was. He was beloved by his many colleagues and friends, a revered member of the medical community. Charming, fiercely intelligent, almost supernaturally fit. But in Harry I always sensed an old, secret despair for what happened to him and his parents all those years ago. His is a story lived countless times, of forced migration, loss and grief, and remarkable resilience despite the horrific start he endured in life.

Harry Peters, soldier in the Third Employment Company, c. 1942

Harry Peters, soldier in the Third Employment Company, c. 1942

I wrote Dear Mutzi as a way into the story of Harry’s early life, when he was a young boy growing up in Berlin in the early 1930s and was tragically caught up in the persecution of the Third Reich. While I was writing, Harry entered his 100th year of life. He remembered certain aspects of his early life with starting clarity, while other parts were erased. Ultimately, this book has been a way for me, as both writer and granddaughter, to convene with this history, these people, events and memories, and bring to light this part of my family’s story.