About copyright

What is copyright?

Copyright is a legal right that gives copyright owners the right to control certain activities with their works. These activities include copying and re-use, such as publication, performance, adaptation and communicating the work to the public (for example, by making it available online).

If you are not the owner of copyright, you risk infringing copyright if you perform one of these exclusive acts without obtaining the permission of the copyright owner. You must consider copyright when you obtain or create copies of items from the Library's collection to re-use them in some public way.

The period of copyright protection in Australia is generally 70 years, but when this starts depends on the details of the work. The duration of copyright depends on whether or not:

- the creator is known

- the work was made public during the creator's lifetime.

Once this is ascertained, copyright duration is calculated based on either the death date of the creator, the date of the work's creation, or the date the work was first made public, depending on the circumstances.

When the duration of copyright ends, a work is referred to as 'out of copyright' or 'in the public domain'.

Why do we have a copyright system?

There are a number of explanations for why we have a copyright system, including that it:

- provides an important incentive for the creation and distribution of intellectual and creative works

- rewards creators for their efforts.

What types of works does copyright cover?

Copyright applies to many different types of works in library collections, including:

- architectural plans

- art works

- books, newspapers and periodicals

- broadcasts (both sound and television)

- choreography

- compilations and databases

- computer games

- design drawings and plans

- diaries and letters

- films

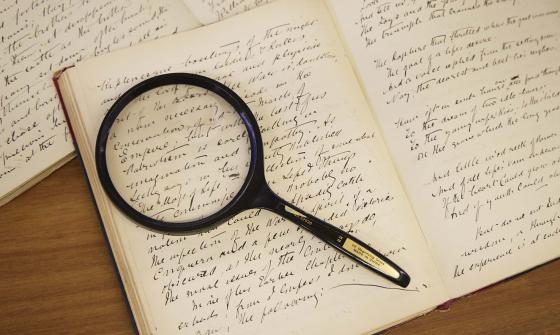

- manuscripts

- maps

- musical scores

- photographs

- plays

- published editions

- screenplays and scripts

- software

- song lyrics

- sound recordings

- websites.

In Australia, copyright applies to both published and unpublished works, and protection is automatic as long as certain basic requirements are met. There is no copyright registration process and an individual does not need to claim copyright by including the copyright symbol and their name on a work (such as © Author Name 2015). Copyright is not dependent on aesthetic or literary merit and protects materials that are utilitarian, short or mundane.

Which copyright law applies?

Australian copyright law is set out in the Copyright Act 1968 (Commonwealth), including all amendments.

Australian copyright law applies to any copying or re-use performed in Australia, even if the owner of copyright in the work you are copying is a citizen of another country. There are reciprocal arrangements between countries which mean that copyright in foreign works is also recognised in Australia (and vice versa).

If you are not located in Australia and you are copying digitised content from the Library's website, you must follow the copyright law of the country in which you reside.

Who owns copyright?

The default rule in the Copyright Act is that copyright in a work is owned by its creator or maker. However, this basic position can be changed in various ways. Copyright owners can transfer their copyright, for example where an author assigns copyright to a publisher. If a creator made the work as part of their job, the employer will generally own copyright. Similarly, for some commissioned items, the commissioner is deemed to be the copyright owner. If a copyright owner dies, their copyright forms part of their estate and can be bequeathed by will. If no specific provision is made in a will for copyright it forms part of the residuary estate.

The relevant government owns copyright in works made by, or under the direction or control of, an Australian federal or state government agency.

Because copyright ownership is distinct from physical ownership, the Library does not own copyright in most of the material in its collections. Even though the Library may own a manuscript or a drawing, for example, it does not necessarily have the right to provide you with a copy or authorise its re-use.

In some cases the copyright owner will assign copyright to the Library at the time of donation or on a specified later date. In other cases the copyright owner will grant an open licence to their work, such as a Creative Commons licence which specifies how the work may be used without seeking the owner's permission.

It is possible for more than one copyright to exist in a single item. For example in a music CD, the composer may own copyright in the music, the lyricist in the words, a photographer in a photo used on the cover, and a production company in the way the music was recorded. It is also possible to have more than one owner of a single copyright, for instance when two or more individuals act as co-authors of a book.

The Library can sometimes provide information that may help you contact a copyright owner to arrange permissions to copy and use material.

What are moral rights?

Australian copyright law sets out a separate and additional set of rights called moral rights. Moral rights give certain creators and performers the right:

- to have their authorship or performership attributed to them

- not to have their work falsely attributed to someone else

- not to have their work treated in a derogatory way.

Moral rights should always be considered if you are re-using and altering works (for example, through editing, cropping or colourising) and you should ensure that attributions are clear and reasonably prominent. See How to acknowledge the Library in your publication for more information on attribution.

Moral rights generally last until the copyright in the work expires. Moral rights cannot be transferred or waived, although creators can provide written consents to acts that would otherwise infringe their moral rights. Furthermore, there are defences to moral rights infringement, for instance, where the infringing act is reasonable in all the circumstances.

Useful resources

- Copyright Act 1968 (Commonwealth) - The current version of the Copyright Act includes all changes made by amending legislation, such as the:

- Copyright Amendment (Moral Rights) Act 2000

- Copyright Amendment (Digital Agenda) Act 2000

- relevant parts of the US Free Trade Agreement Implementation Act 2004

- Copyright Amendment Act 2006

- Copyright Amendment (Disability Access and Other Measures) Act 2017.

- For an overview of the Copyright Act see A short guide to copyright issued by the Australian Government.

- Arts Law Centre of Australia

- Australian Copyright Council

- Australian Digital Alliance (ADA)

- Australian Libraries Copyright Committee (ALCC)

- Centre for Media and Communications Law, University of Melbourne

- Creative Commons Australia

- Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts

- Intellectual Property Research Institute of Australia

- IP Australia

- Resale Royalty Rights