Due to scheduled maintenance, the National Library’s online services will be unavailable between 8pm Friday 29 November and 11am Saturday 30 November. Find out more.

The National Library has a large collection of sculptures built into and around the building, and beautiful tapestries hanging in our foyer.

Lintel Sculpture

Tom Bass (1916-2010), Lintel Sculpture 1968, beaten copper bas-relief, above the Library entrance

The Lintel Sculpture is spread in monumental proportions above the exterior of the Library’s front doors. Comprising over 3 tonnes of copper, the sculpture was transported in 3 trucks to the Library, where the pieces were welded together on site.

The work is based on allegorical symbols based on ancient Sumerian and Akkadian seals dating back to 3000 BC. At the centre is the winged sun, symbolising enlightenment and inspired truth. On the right are spear-like tree branches representing the source root and continuous growth of knowledge. On the left is the curved ark of knowledge, referring to the Library’s place in collective memory and preservation of intellectual endeavour.

Bass was one of Australia’s most fervent advocates of public sculpture. Born in Lithgow, New South Wales, he first studied under the Italian-born sculptor Dattilo Rubbo (1870–1955). After graduating from art school in 1948, Bass embarked upon a series of stylised figurative sculptures, including Ethos (1961) located in Canberra’s Civic Square.

Knowledge

Arthur Robb (b. 1933), Knowledge (detail) 1967, seven copper panels, outside lakeside wall

Knowledge consists of seven panels that run along the outer lakeside wall of the Main Reading Room. They were designed by Arthur Robb, a young architect and draughtsman, with the building’s designers Bunning and Madden.

Bunning said the circles, diamonds, crosses and other shapes, with their rugged ‘Roman’ feel, were inspired by the decorations on gladiator shields. The geometric patterns also echo the motifs of Leonard French’s stained-glass windows.

The panels were fabricated from sheet copper and beaten into profile, probably over timber forms. The artisan was Z.S. Vesely, whose Sydney foundry also made works for Tom Bass. Vesely’s name is inscribed on the centre panel. To match the tone of Bass’ Lintel Sculpture, the panels were specially treated to appear aged.

Two Piece Reclining Figure No. 9

Henry Moore (1898-1986), Two Piece Reclining Figure No. 9 1969, cast bronze, Patrick White Terrace

Henry Moore's Two Piece Reclining Figure No. 9 sculpture can be found in the Library grounds near the front of the building, and has long been associated with the Library.

The work is one of nine two-piece sculptures Moore created, starting in 1959, and this is one of seven casts (the other six went to the United States). Originally, the sculpture was to be displayed on the Library’s front podium, however it was felt to be inappropriate for this location. Therefore, the sculpture was placed on the Library’s boundary on a plinth designed by Walter Bunning. Moore approved of the new location: ‘I think you are right in placing it the distance you have done from the building, for then the sculpture will take on its own scale’.

Moore believed that by dividing a figure in two (an upright torso and a thrusting leg) he could develop tensions within the body unachievable in a single unit. The sculpture’s shifting perspective creates a work full of surprises—at one moment suggesting the body of a woman, the next the shape of eroded rocks or a hill. Moore described the sculpture as being like a journey, in which the viewer travels around the piece and returns to a different view.

Moore was born in Castleford, Yorkshire, and studied sculpture at the Leeds School of Art and the Royal College of Art, London. He taught at the Royal College from 1924 to 1931 and later at the Chelsea School of Art, London. Moore is regarded as one of Britain’s most eminent modern sculptors.

Three Tapestries

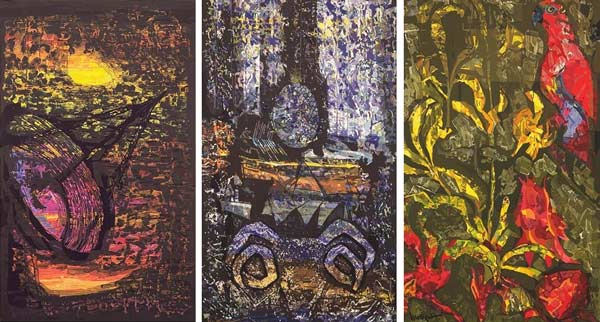

Mathieu Matégot (1910-2001), Three Tapestries 1968, Australian merino wool; 518 x 305cm (each), Library Foyer

The three large tapestries hanging in the Library’s foyer were conceived as harmonising with Leonard French’s stained-glass windows. Woven in Aubusson, France, the tapestries are bold in design and make forceful use of colour to anchor the foyer’s expanse of travertine marble.

Jean Lurcat (1892-1966) was originally commissioned to create the tapestries but he died before completing the designs. Mathieu Matégot, Professor of Art at the prestigious École des Beaux Arts in Nancy, France, was chosen to be Lurcat’s successor. Matégot began working on the tapestries in 1966 and they were installed in 1968. The works were designed to be best viewed from the mezzanine level.

The first tapestry depicts the radio telescope at Woomera, South Australia, representing the technological times in which the Library was built. Woomera was NASA’s first deep-space station located outside of the United States. It participated in a number of early important space missions.

The middle tapestry depicts Australian flora and fauna. The two-metre parrot represents ‘Terra Psittacorum’ or ‘Land of Parrots’—a name given to the Australian region in early navigational charts.

The third tapestry has a multitude of themes. Starting from the top, it shows a blue area symbolising the Great Barrier Reef. The pineapple evokes tropical Australia and the riverboat and the outline of the Sydney Opera House represent urban life. The ram’s head stands for wool, Australia’s major export at the time, with the brown area at the bottom representing the land.

Matégot was born in Hungary and lived in France. He initially worked in theatre design and also crafted furniture but he is best-known for his monumental tapestries.

Stained-glass Windows

Leonard French (1928-2017), Stained-glass Windows 1967, Belgian and French chunk glass and concrete, 345 x 130 x 5cm (each window), Bookshop and bookplate

The 16 stained-glass windows (six pairs and four singles) in the Library’s foyer are made of Belgian and French dalle de verre (faceted or chunk glass style). Embedded in concrete, the blocks are cut to maximise light refraction and create dazzling patterns of colour.

The windows include motifs of crosses, circles, suns, stars and mandalas in a palette of over 50 colours. The broader theme comes from the planets - Venus in tones of blue and Mars in red. Leonard French commented that the planet theme provided him ‘with a subject matter that has been the concern of artists from the beginning of time. The mystery and wonderment allows for a complete poetic interpretation’.

As well as being decorative, the windows originally served a more functional purpose, reducing the amount of outside light entering what was the Library’s foyer exhibition area. In the morning, the sun glows warmly through the glass—with a conversely cooler light filtering through in the afternoon. The windows were installed in 1967, before the development of the Library’s bookshop and café, which now incorporate them.

French was born in Melbourne and studied at the Melbourne Technical College (1944–1947). In the 1960s, he became internationally renowned for his semi-abstract paintings with crucifix-like forms that evoke Byzantine art. French likened himself to the Homeric voyager, the hero Odysseus. In 1968, The Sydney Morning Herald declared it ‘the year of Leonard French’. That same year, in addition to the Library’s windows, French’s ‘biggest stained-glass ceiling in the world’ became the highlight of the new National Gallery of Victoria building. Another of French’s chunk glass ceilings is on 24-hour view at the National Art Glass Gallery, Wagga Wagga.

Further reading

- A different view: the National Library and its building art 2004, Canberra: National Library of Australia, nla.gov.au/nla.cat-vn3083203

- National Library of Australia News August 2008 issue celebrated the 40th anniversary of the National Library building

- Blakeley-Carroll, Grace, Luminous Legacy : Grace Blakeley-Carroll looks at the techniques and inspiration behind Leonard French’s coloured glass windows at the Library ; Unbound