By Peter Crowley, author of Townsend of the Ranges

When I tell people that I wrote a book about a colonial surveyor called Townsend, and that I spent almost seven years researching it, I am usually met with quizzical looks—it is rare for anyone to immediately recognise the name—followed by many questions. Are you a professional historian, or perhaps a surveyor? Definitely not. Was he your ancestor? Well, no. Why choose him? Why indeed. What would possess a medical doctor to pursue the ghost of an obscure government officer across the landscape of Australia’s south-east?

My response begins with the observation that my subject, Surveyor Thomas Scott Townsend, whose career extended from 1831 to 1854, was far from unimportant. His name was given to Australia’s second highest mountain, next to Mt Kosciuszko in the Snowy Mountains of New South Wales. He was, in fact, the first European to traverse the crest of the Main Range that includes both peaks (although Mt Townsend is not, strictly speaking, part of the crest of the watershed between the Murray and Snowy Rivers).

Not only that, but he was the first European known with complete certainty—not with elements of speculation, or by weighing probability—to have stood on the summit of Mt Kosciuszko. In February 1847 he took his survey line right over the top of it and placed it on an official survey map. He was also the first colonist known to have identified the springs that were the source of the Murray River nearest to Cape Howe on the Great Dividing Range, fixing the inland end of the straight-line eastern border between Victoria and New South Wales (known today as the Black-Allan line).

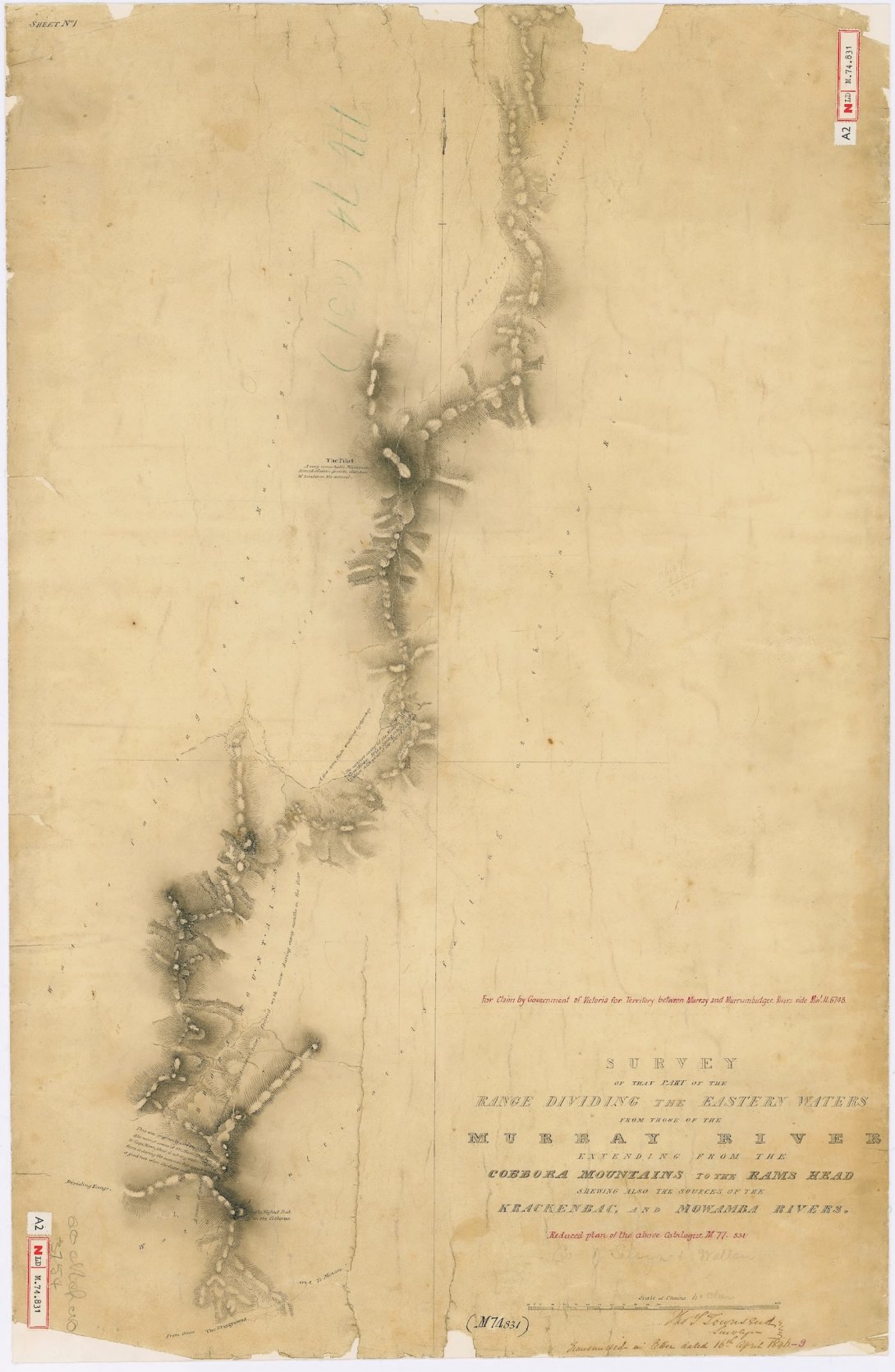

Townsend’s maps were a foundation of my research, just as important as the many hundreds of pages of professional letters he left behind. These stunning drawings were in many instances the first survey department maps of the regions he charted. My favourites were those of the Snowy River catchment, a product of his pioneering surveys of 1842 and 1846. A map of the Snowy River’s bend in the mountains of southern New South Wales graces the back cover of my book, with the waters of the river-coloured blue by Townsend’s careful hand. It is a fine example of his craft. Lacking contour lines, hachures are used with striking effect to evoke the drama of this country in a way that modern maps do not. In many cases, he drew his maps in truly wretched conditions, sitting in a cold and lonely tent in the wilderness.

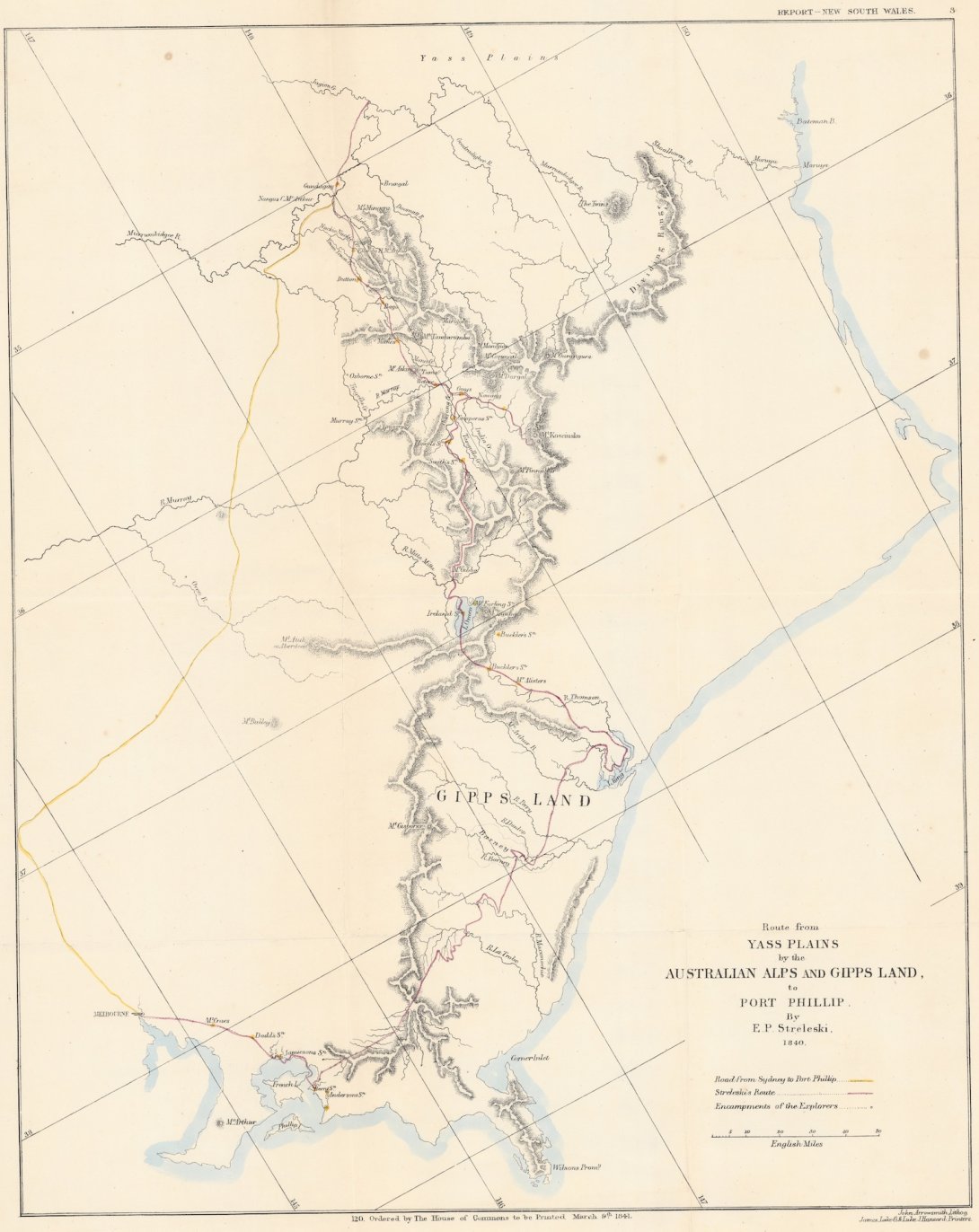

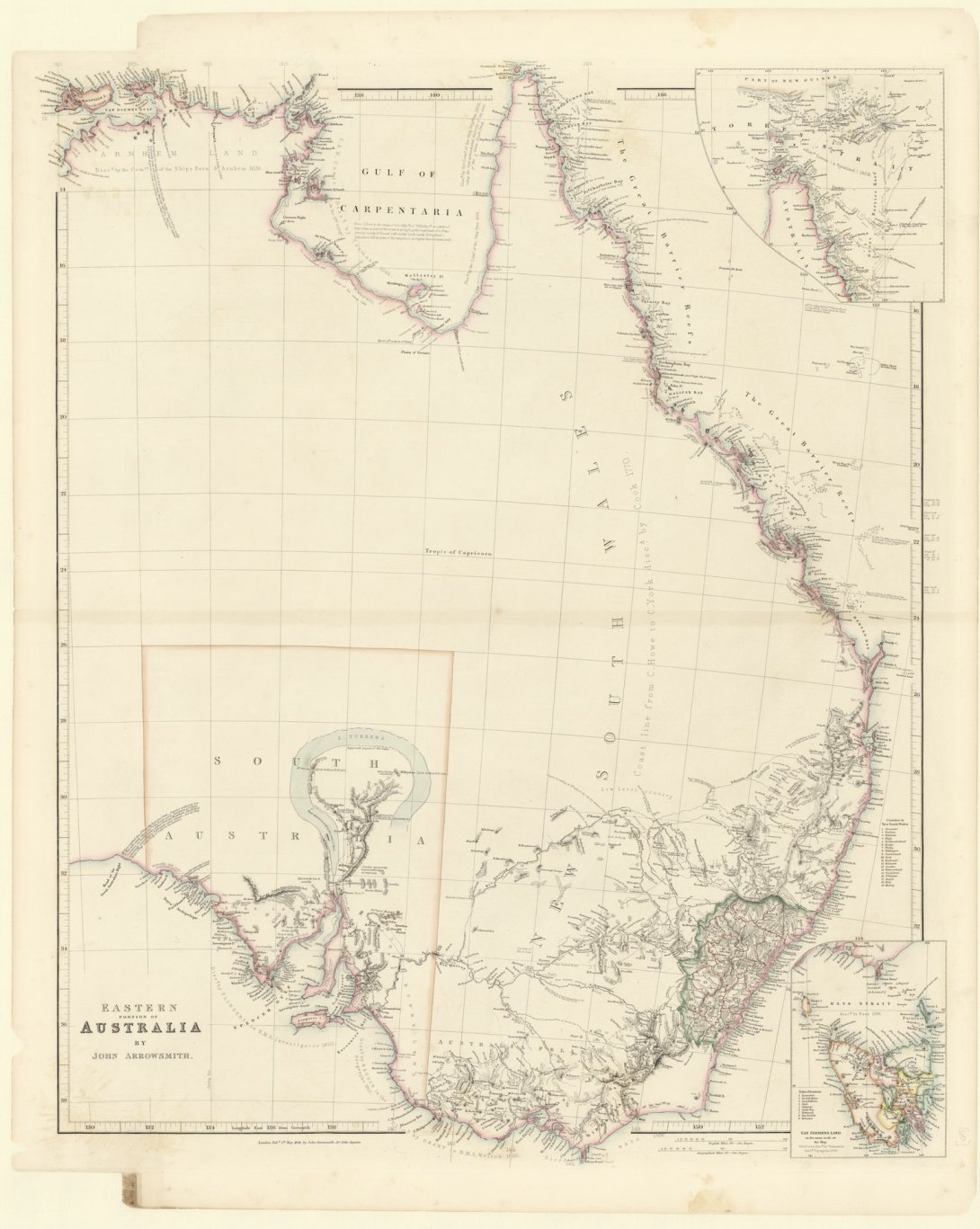

These drawings made a deep impact on me. I was familiar with the early maps of the Australian Alps and Gippsland drawn shortly before Townsend’s surveys were undertaken, but these could not hold a candle to the maps Townsend created. The National Library of Australia has a version of Strzelecki’s famous map of 1840 showing his route from the upper Murray to Westernport, and the stockman Stewart Ryrie drew maps of his journeys across the mountains from Monaro to Gippsland’s far east. But valuable as these were at the time, they were the rough sketches of explorers, and they did not compare to the meticulously measured maps plotted by Townsend. These were the charts that formed the official record of the country’s geography, as they deserved to be, and you could use them to navigate even today.

The south-east Australian terrain of rivers, ranges and watersheds is bewilderingly complicated, particularly in the alps, and the essential topographic information took a long time to stick in my mind. I needed to do a great deal of repetitive study to chart Townsend’s movements across the landscape precisely, and to appreciate the place of his surveys in the growth of the European understanding of the land. I also needed a sense of how the growth of European map knowledge developed over time. What territories were already surveyed when Townsend began his work in the 1830s, at the threshold of the squatter age, and what work remained to be done? How were these land acquisitions—in reality, seizures from the Traditional Owners—divided up according to the conventions of British system of land tenure?

This was, in essence, another way of asking the question: how did colonisation spread beyond Sydney, and give rise to the profusion of counties (the major administrative division of land), and the villages, towns and cities that were established in the wake of pastoral expansion?

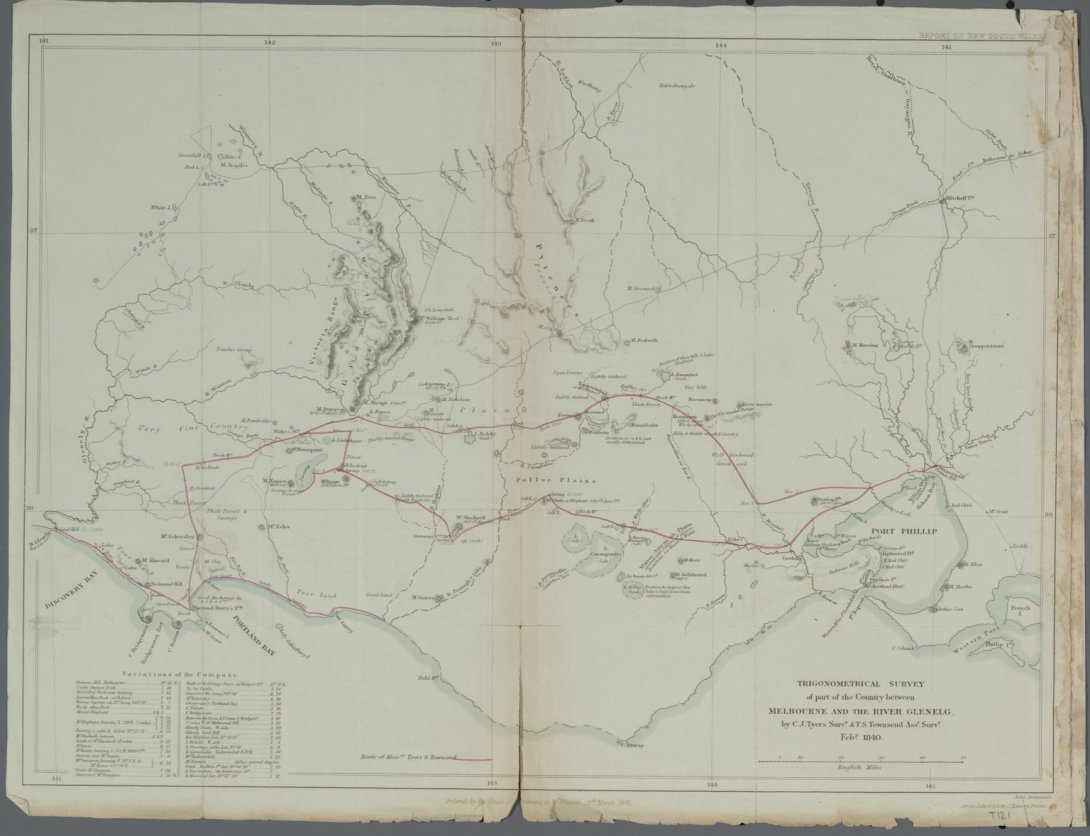

It turned out that Townsend was deeply involved in this phase of European occupation, over a huge extent of territory. As I point out in my introduction, if you live in the south-east, there is a good chance that your town or district was influenced by his work. My geographic baseline of pre-Townsend colonisation came from prolonged mulling over the rich collection of historical maps held by the National Library, available online, including many early parish and county maps. Important maps from this resource are included in the book, including the beautiful map created by Charles Tyers and Thomas Townsend on their survey from Melbourne to Portland Bay and the Glenelg River in the summer of 1839-1840, one objective of which was to establish the position of the border between Victoria and South Australia.

Other treasures in the National Library collection were essential for the creation of Townsend of the Ranges. One was simply a family letter written in 1862. I did not know of its existence until I’d almost finished writing the manuscript, and I owe a debt to members of the Canberra local historical community for alerting me to its survival. Without giving away details of the plot, this letter was written by Jane Davis, the mother of Townsend’s wife Francis Emily Davis, to her brother in England. It narrated the origin of the events that led to Townsend’s departure from Australia, just after his appointment as acting Deputy Surveyor General of New South Wales in 1854. It was a priceless primary source that took me into the story more deeply than the newspaper accounts published during court proceedings of the early 1870s, when Townsend’s will was disputed. It was also a rather emotional read for me, and still is. The final chapter of Townsend of the Ranges is richer, more complete, and more heart-rending, because of its preservation.

Apart from maps, readers of the book will notice among the illustrations another National Library gem. The Llibrary holds (and has digitised) the photographic materials of the Australian Inland Mission. A large number of these images were taken by the Rev. John Flynn, including lantern slides from his missionary days in Gippsland in the first decade of the 20th century. Among them were haunting images of Gippsland’s Snowy River country. They were the perfect companions when I came to write about Townsend’s experiences surveying in the mountains, capturing as they did the brooding, isolated character of the rugged borderland which can unsettle even the sturdiest mind after long exposure.

For me, two images in particular evoked the creeping darkness and solomn tone of this part of Townsend’s story as he toiled in forbidding remoteness in a growing state of exhaustion. One was a slide of a stockmen’s hut on the Deddick River (Townsend’s ‘Jingalala’, a name regrettably lost on later maps) while the other was a view from Mt. Tingy Ringy on the Black-Allan line toward a snow-capped Mt Kosciuszko.

Both of these echoed the uncanniness and disquiet I have often felt in the Snow Country, the awareness in your bones that the high places barely tolerate your presence. Many of us, I suspect, have this intuition, and no amount of European control over the mountains will ever manage to vanquish it from our imaginations.