Cathie Oates: Well, good evening everyone. A very warm welcome to the National Library of Australia and to this very special event, A Brief Affair: Alex Miller in conversation with Tom Griffiths. I'm Cathie Oates, the director of Communications and Marketing here at the National Library of Australia. As we begin, I would like to acknowledge Australia's First Nations peoples, the First Australians as the traditional owners and custodians of this land, and give my respects to their elders past and present and through them to all Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Thank you for attending this event, either in person or online. Coming to you from the National Library on beautiful Ngunnawal and Ngambri country.

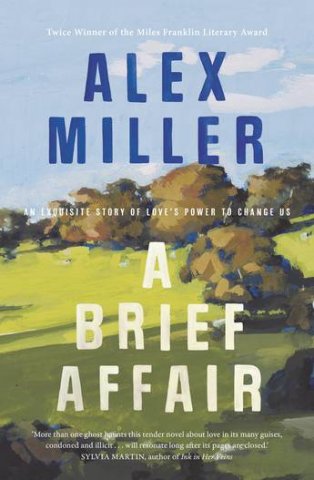

Tonight, Alex Miller and Tom Griffiths will discuss Alex's 15th book, A Brief Affair. It's the story of Dr. Francis Egan, a woman who has it all, a loving family and a fine career until a brief perfect affair reveals to her an imaginative dimension to her life that is wholly her own. Fran finds the courage and inspiration to risk everything and change her direction at the age of 42, so a mere spring chicken. I'm not going to give anything else away, but I spent some time with these characters on the weekend and it is just beautiful, wonderful writing and it was a joy and a pleasure. Thank you.

Alex Miller is the award-winning author of 13 novels, one biography and one collection of essays and stories that has been published both internationally and also widely in translation. Alex is a two-time winner of the Australia's premier literary prize, the Miles Franklin Literary Award, first in 1992 for the Ancestor Game, and again in 2003 for the Journey to the Stone Country.

Tom Griffith is an historian whose books and essays have won prizes in literature, history, science, politics, and journalism. His books include Hunters and Collectors, Forests of Ash: an Environmental History, Slicing the Silence: Voyaging to Antarctica, Living with Fire and The Art of Time Travel: Historians in their Craft, and I had to race through those because there was- I enjoyed saying all of them. He writes for Inside Story, Griffith Review, Meanjin and the Australian Book Review and is Emeritus Professor of History at the Australian National University. He has lived in the Macedon Ranges since 2018. Please join me in welcoming Alex Miller and Tom Griffiths to discuss A Brief Affair.

Tom Griffiths: Thanks very much for that warm introduction, Cathie, and we're delighted to be here in Canberra, aren't we? Alex? And we are delighted to be here with you and it's an honour for me to be in conversation with Alex about his new novel and we will probably take an excursion into some of his other writings as well as we discuss. But Alex is going to begin with a reading from the novel, so over to you Alex.

Alex Miller: Thanks Cathie, and thanks Tom. Cathie's disappeared, but did you sit down? There you are. Yeah, I mean we are here together because we're friends essentially, and we both read each other's work and talk about it, have lunch, drink, and stare at each other wordlessly sometimes, as you do. You can communicate more in the silence than you can with the words always. I'm going to start at the beginning. It's a very brief chapter and it's only a couple of pages, but it's where you begin when you read a book, isn't it? Usually, I mean, I usually begin at the beginning. I dunno. When I write a book, I begin at the beginning, even though sometimes the end is the thing that has lured me into trying to write the thing.

'Before she had a shower and still in her dressing gown, Fran sat on the edge of the bed and wrote in her diary. It was Wednesday, middle of her first week back already. Since China, she hadn't been able to find her old enthusiasm of the job in anyway, the new campus was haunted. She had the unsettling feeling of being unwelcome there. She didn't believe in the paranormal and ghosts or anything like that. Of course, but at the same time, the place was creepy. She wrote 'the sense of unease or even horror and a place where terrible things have happened is familiar to me'. She'd been meaning to make this note ever since she began working at the Sunbury campus. In fact, ever since she became an Australian probably, but for some reason she'd never quite got around to doing it. It had nagged at her. Now it was done, was on paper. She read over what she'd written. It would do. Her feeling was on the record, but her question remained, what is that residue of unease which is left behind like a stain on old wallpaper long after the deed? What does it speak of to us? What is it we know in our skin when we feel that chill?

Other people felt it too. Not everyone, not Carlos Skinder, the Dean of Studies. Carlos claimed to feel nothing, which was probably the truth. But some of her colleagues did enough of them to reassure Fran that it wasn't just her own fancy. She closed her diary and slipped it into her laptop case, and she stood up from the bed, took off her dressing gown, and looked at herself in the wardrobe mirror. She ran her hands over her belly and lightly touched the moon shaped scar on the inside of her left thigh. Until China, she'd always thought of the scar as her wound. She and her best friend Penny, when they were 10, clambering around on the roof of the abandoned house next door and the awful scream that came out of her as the roof collapsed under them. When her mother arrived, she gave her attention and sympathy to Penny who'd received only a small cut to her scalp and told Fran to get up and stop making such a fuss,

Watching her mother attending to Penny that day, the pieces of the puzzle came together for Fran. And she understood in a flash that her mother was not withholding her love but was unable to love her. Simply that. And she made what seemed to her then to be the first real decision of her life. She would cease begging for her mother's love and would rely on herself. The wound, after all was for life. Margie was singing in the kitchen.

Fran took a shower, then got dressed, she dreamed she gave birth to a male child was suddenly there, it lay asleep on her bed. When she looked at it, its eyes opened and it began to assess her coldly. Her secret life was open to it. She had no love for it. Seeing it there, made her nervous dressed for the day, a smart looking woman of 42. Her satchel on her shoulder, her laptop case in her left hand, Dr. Francis Egan came out the back door and headed for her car. The landscape of field and farm was at peace. The rusted tin roof of the old stone cottage down the hill, glistening with frost, a soft white mist lying along the creek flats below the house, the sound of the creek in the perfection of mourning stillness, Tom stood in the doorway behind her holding the fly wide door open. Watching her leave, he watched her walking away from him along the gravel drive towards the old stable where her yellow reno was parked. The touch of her lips still cool on his cheek. Little Tommy came and stood beside his father. He called 'bye Mum' at the boy's anxious cry. She turned and waved and called back to him a catch in her voice 'bye darling'.

They stood watching her leave the man and the boy, and when she stepped on a loose stone and appeared to stumble, they both flinched and would've run to her aid. But she recovered and went on her free hand pointing down at the offending stone. Then she was gone, but they still stood man and boy in the cold air as if a question remained with them, a pale dust in the stillness of the morning where she had been. They might've been watching the flight of galahs now that swerved across the lower paddock to settle and feed on the roots of the onion grass. She parked at the railway station and found a seat on the train. She didn't open her laptop, but sat looking out the window, watching the countryside sliding by. Grey clouds were banking up from the south and thickening the light. It was probably going to rain later. After all, despite the confident forecast of fine weather from the bureau, seeing the beauty of the glossy red cattle and the scatter of white sheep grazing on the vivid green winter grass with its glistening patches of frost, Fran was invaded by a familiar wave of sadness. The sob gathered in her throat and she closed her eyes. The shriek of the train's warning made her open her eyes again. A line of shining cars waited at the level crossing as the train thundered past its whistle howling the battle cry of a triumphant enemy who would scatter them all to hell. She closed her eyes again in the warm compartment of the speeding train. It was a reassurance and a terror to think of him. She didn't resist the memory. She couldn't resist it. It came vivid and unbidden into her head.' I'll stop there and if you want to know what the memory that came vivid and unbidden into her head was, you'd have to read on a bit.

Tom Griffiths: Thank you. Wonderful hearing you read your own work, Alex. I had the privilege of hearing you read from Landscape of Farewell here in the National Library many years ago, and I went straight up to the bookshop and bought it. I couldn't wait. I you

Alex Miller: Have to

Tom Griffiths: Do, just couldn't wait. Don't forget. It was a wonderful glimpse of the treasures within that book as indeed you've just given us there. It's such a richly satisfying novel, Alex. It's luminous. I wanted to linger in it. I wanted to dwell in it. I didn't want to let it go. I wanted to luxuriate in the vast spaces that opened up for reflection, for reflection about the people in the book and reflection about my own life. I think that's what good writing does. It really stirs - not only opens a new world, but I think it makes you think of your own world in new and different ways as well. So it does open up all those spaces for reflection and it made it, I didn't want to let it go. I wanted to stay in those pages. You, I mean, I think all of us readers are really intrigued by the magic of the novel and of the creative art, and I wonder if you could tell us what are some of the sources of this novel from your own life and from your writing in general?

Alex Miller: Yeah, it's a terrific question and it's one that I think writers ask themselves all the time at different levels. But the main answer comes from your great readers, the people who read your work and everybody reads their own story, and you see that if you can be bothered and you probably can't and I can't. But whenever I have read a spectrum of reviews, they've all read a different book. It's their own book they've read because they bring their life to it. And the life of reading is not the life of writing, but they're the same. They're linked together in that way that the underground of our own lives speaks to us in ways and in tongues that we're scarcely aware of and not able to really control or be self-conscious about. You might have a self-conscious reason in answering Tom's question that 'I wrote it because I wanted to do justice to blah, blah, whatever.' No. Okay. There are other layers always.

And I remember with a book called, I think it was my last novel before this one, before Max came out, The Passage of Love. And in that there's a woman prisoner at local prison, and this is a true story. Everything's a true story I suppose, but I mean this is true in a kind of factual reporting kind of way. And I was dreading it a bit because the novel that the prisoners had read, and they were all women and some of them have been sitting in there for seven years, was Coal Creek, which was set in a prison. And I've never been in prison. I haven't got the inside story on that stuff, literally. So I was a little bit anxious, very anxious. When I got there, there was already one woman in the audience in a it, it was like a seminar room at a university and she was sitting there and she had all my books arrayed there with stickers in them. I thought, oh Christ, I'm done this time. This is it. I might have to stay here. There were no handles on the doors. You had to have a special person to open the door. So it was a bit intimidating just being in there, let alone coming across somebody who then announced the fact that she'd read all my books.

She looked like an educated middle class woman to me. As a matter of fact, they all did that where were the sort of crazies, they weren't there. Where were the criminals? This book deals with what was once called lunatic asylum, and it's inmates and it's inmates were deemed to be crazy, nutcases, whatever these days. Of course we've changed the names. We don't call people by those crude names anymore. We call them minimal, refined way, unbalanced for some reason, or they've got this or that or other thing.They're not crazy though. They're not crazy. We are crazy.

And there is a little section in the book where the main character, Francis is going through a map that she saw of the building and there is such a building, such a map, and she sees that there were these wards and places for recalcitrant females and she thinks, what's that? Then we're all recalcitrant females today, we, it's happened, hasn't it? We've come out of the box, we've done it. And she's right of course, because insanity of one age is the sanity of another age. And in a sense it's got something to do with the question that Tom asked, which is that we don't really know what's going on. We think we do and we have motives that are opaque, aren't they? I mean, that woman who'd been in the prison revealed to me a motive about my writing that I was totally unaware of. I'd never touched on it. She said, I wonder if you could comment on a question I have about your work. I said, sure, of course. That's why I'm here. In my sort of dry voiced response, I was pretty scared actually. I said, she's going to bring me undone, this woman. But she said, why do you write about absent mothers?

Saying it is, I'm moved again. And now at the time I was so moved, I couldn't speak for a while. The theme she said in my silence, she took to be sort of hesitation. I was just incapable of talking to her because she'd touched on something fundamental in my life that I hadn't forgotten, but I'd never associated it with my writing. She said, there's several of these books here and I can show you the places where the mothers are absent, they're either dead or they've moved away or they're simply not there or they're not good mothers, they're absent in the sense of not being able to love. What was this girl here, Francis, when she was 10 years old, saying again, there it was. I didn't think about that, but there it was. And this prisoner woman asked the best question and the most revealing question I've ever been asked.

And it really struck me to the core. So there was a motivation there that I'd been unaware of all my life, a theme of the absent mother. And it snuck into here too. I hadn't realised that to be honest. Wow. So we dunno what we're doing. We think we're doing one thing and we're doing something else. On the surface I had other motives for writing this story. We were sitting after I'd finished Max, which was a sort of five year job and research travel learning German, which was an enormous challenge for Stephanie and I. And Stephanie was a hundred percent with me on the writing and research for that book, took us around the world eventually to Israel where we met Max as some people. And yeah, what was I saying?

Tom Griffiths: I think you're still reflecting on the sources of this novel and some of the sources of which you are conscious, I guess.

Alex Miller: Yeah, was I?

Tom Griffiths: Think so. Just go with it, Alex. This is fascinating itself, but well, can I suggest that part of what of what you are drawing on I think is certainly the environment in which you are living now, the landscape as in all of your novels, is very much a character, an agent that the gold fields is there in this novel. Also part of the context is academia, universities, and Fran of course the main character is coming to a decision about her future in the university. And that's one of the ways in which her life may change.

Alex Miller: But she sees the worst of it.

Tom Griffiths: Yes.

Alex Miller: I think, I mean it may well be that there is worse than she sees, but pretty much the worst of it, where teaching has been long subsumed under the need to do something about funding shortfalls. And that's the main concern.

Tom Griffiths: And it's a university which is in an old lunatic asylum. Absolutely. As they called it. And I think just to return to one of the things you said earlier, I feel the novel plays with this idea of madness and sanity. In fact, it inverts it throughout almost systematically. The people identified as mad seemed the most sane.

Alex Miller: And the mad woman in the attic, of course in literature of the 19th century was the mad woman in the attic of society in the attic of shut away. I mean so emblematic that to us it sort of screams in an obvious kind of way that it didn't though. Tom and I were talking about the past earlier, and I'm a great official and one of the reasons we are good friends is because we met through his work and I asked him a question that he answered with one word and I thought it was the best answer I've ever had. Mostly people don't like me now. I just rambled on for until the 40 minutes are done and then we just stop. But Tom and I met through Morag Fraser, who I see is here tonight, an old friend of both of ours. But Morag had asked me to come and speak and she'd also asked Tom and I was sitting in on Tom's address and I'd written a book called Landscape of Farewell, which he referred to just now.

And in that there's an account of, the massacre at Cullin-la-ringo, which is not a massacre of black people by white people, but is the other side of the war. Henry Reynolds and other historians have insisted for many years, and perhaps I say Henry, because he was a sort of leading voice in this, that there was a war. And at the same time, there's a sort of denial implicit in the lack of accounting for strategic intelligence in Aboriginal attacks. There are no strategically intelligent generals, leaders who organise things in a way that makes them enormously successful. And the sort of best example of that was the massacre at Cullin-la-ringo in the Central Highlands of Queensland. Why did I write about that? When I first came to Australia, I had a job on a property called Golans, on the headwaters of the Negoa River, Kona Creek.

And just down the road from us was Cullin-la-ringo, and of course the subject Cullin-la-ringo. That was back in the fifties, 53. I came here. It was a subject of discussion still among the old people, white people, black people weren't thought of as old people then. They weren't thought of much at all because this really important battle, not a battle, a massacre of white people took place there. It's scarcely mentioned at the back of that book, Landscape of Farewell. I give a bibliography. It's very, very brief and the reason for that is it hasn't been dealt with as a success on the part of the Aborigines. The first motive I had for writing it was that Frank Budby, who is the leader of - Frank, died a couple of years ago - that he was the leader of the Bararda Barna people in Central Highlands. And he asked me, you can do it mate.You can write the story of Cullin-la-ringo from the Aboriginal point of view. I said, well, of course I can't, not possible has to be a dream. He said, well, with you it would be a bloody dream, wouldn't it? And what he meant was a kind of dreaming. He also told me often where I got characters from and he would say, the old people give it to you, old mate. But what I would say is my unconscious gave it to me, and the same I would have the similar sort of meaning. The past, the deep past of our lives of our cultures gave it to me. And so my initial motive was to satisfy Frank's need to see. I mean, he could tell the story, but he couldn't write it. He'd tried plenty of times and I tried to encourage him to write it, but he said, no, no, you're the writer. You write about it.

And when I was in Hamburg, I met some people who were at that point of reclaiming some, of course it was in Germany and the old academics, the old 70 year old type, a lot of mainly men in dark suits were pretty much in denial amazingly about the Holocaust. And I thought, this is my chance. I've got to be ruthless and see what these people really think. And Max, of course, even then was of my mind and his life and how he ever survived that situation. And so I asked them straight out, what did your dad do during the war? You know, did you ever ask him? Some got seriously angry, especially when I persisted and I did. I was quite rude and I think I had to be, I felt I had to be to get to the bottom of it and not just let them be evasive. Others, the younger ones, the young PhD students and people like that were dead keen to talk about it. And also to talk about the dispossession in Australia. And they saw parallels and they wanted to talk about those two things and to learn something from me and I wanted to learn something from them. And it was really wonderful experience in the end being there.

And the wonderful professor who helped me, he drowned a couple of weeks after I left Unbelievably drowned in Hamburg. There's these two lakes and he was a good swimmer. I know he'd got cramped or something. But yeah. Anyway, my initial motive was to do it for Frank somehow find a way of doing it. And when I went to that, I still hadn't resolved the question in my mind, how on earth am I going to do this? When I went there, I was warned that one of the people at that conference is going to be

Somebody who is a gatekeeper, a very loud, aggressive, confident, demanding gatekeeper of Aboriginality at stories and its affairs. So watch yourself mate. And at that time Journey to the Stone Country had come out and yes, I was a little bit worried and I thought, so what? Fuck him. And anyway, got there and I got to this beautiful old library where they were having the conference. It was a beautiful old place. It had been a private library, and there was a woman in a Ceres coat with a flaming sort of scarf holding up Journey to the Stone Country standing in front of me with her back to me going, pay attention. This is the white fellow getting it right. I thought, that's her, that's the gatekeeper. And it was, we went out, met each other and she said, oh, she, oh God, it's you. I said, it's you. She says, I was scared. I was even more scared. I said, let's go and have a drink. You're talking to an Aborigines. I said, no, let's go and have a drink. So we went and had several drinks. I dunno, we didn't go back that day. But yeah.

Tom Griffiths: Can I ask, interrupt and say,

Alex Miller: Please do.

Tom Griffiths: Your love of history shines through all of your writings. And of course Max, your last book was history, and that was you writing a true story confined by the evidence available. And one of the lovely things about Max, I think as a book is the way in which you wrestle with the limitations and the opportunities of writing history. And you use the phrase, 'the magic of the simply true' as one of the liberating dimensions that you found in writing history. Can you say some more about that?

Alex Miller: Oh yeah, it was lovely. I mean, I had never attempted to write history or memoir before, but it was critical. I didn't want to ever fictionalise Max or my memory of him. He was such an important person to me. He'd become a mythic sort of stream in my life and he lived in me and still instructed me.

So when I came to write about him, I just wanted to get the facts. I wanted to get the things that he'd told me and that were kind of embalmed in my memory. Nothing was in writing. I wanted to unbind them and have a look at what they really were and what they represented. And my greatest fear was that maybe he'd made some of them up, maybe Max after all when I came to confront these questions was, and I remember this, I was in Berlin at the time when I decided to do this, and I remember having this fear. I thought, supposing I find that Max is the hero I've had, and he wasn't. So that was pretty confronting and thought, I still got to do it. So I did. And it took five years to make sense of it all.

Tom Griffiths: So was it a liberation to you to return to fiction after your five years of wrestling with history, or do you not see them as separate genres in that way?

Alex Miller: Well, I definitely don't see them as all that separate. I mean, I've read most of your books and you've reeducated me about writing in many ways and educated me about it for sure. Definitely about the forests. I mean, quite clearly have a different sense of the history of the great forests in Australia since reading his book on the Forests of Ash, what a title after Ash Wednesday and that. But yeah, I'm not going to attempt to say what the difference is. I mean, there's a poetic truth, I suppose, what people call a poetic truth. There's a truth in our hearts that may not match up to the facts, or it may do, it may illustrate the facts. But with Max, I wanted to get the ground. I mean, I was talking to Jim Davidson about this the other day. Jim's just published a really wonderful biography, double biography.

And in that he talked about leaving the ground of the facts on the trampoline as it were, and then, well, you've got to come back down again. And the trampoline had better be there in a sense. The metaphor being the trampoline is the facts. And that's the same for me and has always been the same for me with fiction, writing a book, most of which was- much of which was set in Paris and also then in Tunisia would've been pointless if in Tunisia people had said, what a load of rubbish that's not Tunisia or in Paris had said that. But both parties and with The Ancestor Game was published several times in translation in China and is still taught there, came out here in 92. But to me that's critical. And it can only be. So if the facts are important to you, I mean we are all human beings. That's all we ever are, any of us. The sooner we wake up to the fact, the better. As you know, it's not them and us, it's not people in wheelchairs and the rest of us. Is it? Wheelchairs supposed to be up the back trying to get in and all that sort of thing. And also all the other thems them and us. Let's get over it for God's sake. We're just people. We're human beings. We're all going to die. And the sooner the better. No

Tom Griffiths: Many of us. So with this novel A Brief Affair, I think you said that it was going to be a ghost story. Is that how it started? Because ghosts are throughout it, aren't they? Ghosts and spirits?

Alex Miller: Well, I think so, yeah. I mean, not in any sort of exor, exercising, ghosts type way.

Tom Griffiths: A place where Fran works is haunted. Her office is the old cell, 16 in the lunatic asylum now turned into the Sunbury campus of the university, the School of Management, no less. Did you have fun inventing a school of management,

Alex Miller: Alex? No, I just told the truth about it. Look, it was a school of humane management under my wife. It wasn't a school of managerialism at all. Quite the opposite, but, which of course is hard to, I mean, there are schools of management that are humane management, and Steph, who's sitting over there, knew all about that because that's what she was the School of Humane Management. Not that that was the official title of course, but when I'd finished Max, our daughter was visiting us from Berlin where she's a DJ or was she's just come home now and we're sitting around and she said, what are you going to do next Dad? Max had come out and we started for some reason, talking about the way in which Kate and I, our daughter and I are sort of easily haunted people. We think that was a creepy place. And we sort of clutch each other a bit. Steph sails through saying, what I'm going to do here as I'm going to bring this and that together, we say it was haunted mum. Sorry. So she wasn't a person who was sort of subject to haunting when she was working at Sunbury. She had to change her office because it was too haunted for her.

So when I went there walking the great old, beautiful, ugly, beautiful, terrifying flagstones of the flaws that echoed through the place, yes, immediately I felt it too. And I thought, gee, Kate, she wanted me to come in here. And that statement about the suffering and terror applies, it seems to me, to Australia too. Australia is haunted by. consciously and unconsciously, by what we've done here. And that's the case I think with all colonial countries and part of that history and the history of pretty Well, any country has these sorts of hauntings in it. You don't want to deal with it directly. I mean, what's the point? But you really don't want to forget it either. And when it occurs in the book, it seems to me that she's talking about that as much, talking about being an Australian as much as she's talking about anything else, even though I don't say that. But some people pick up things like that and some won't. It doesn't really matter. They read the book.

Yeah, what happened? Sorry, I know I do get off the point, don't I? But what happened was we thought, so Kate said, why don't you write? I said, I want to write something a bit light after Max, it's taken it out of me. It's been terrific journey. It's such a struggle to get to a point where it could be expressed and makes sense. And she said, why don't you write a ghost story? I said, alright, I will. But I couldn't, interested enough in the paranormal or ghosts for that to hold me. But what did hold me was the difference between the interior life of a person, which when I was young, I had pre novels that didn't get published. They weren't any good. And the reason now I know they weren't any good was because I tried to write about the interior life and I didn't have the skills to meld the interior life with the physicality of the story, the reality of it, the scenic effects of the story of how could I do it?

And I gradually, I mean in a sense, The Ancestor Game is a failure to do that too, because it moves from one thing to another rather than melding them all together. I look back at that now. I mean people, critics mistook it for postmodernism or something. I didn't even know what post-modernism was. They thought, oh well this guy's you right and postmodernism mate, it must be good stuff. But it was actually because I wasn't able to bring the two together into a single story, which is of course what they are. And to get back briefly to my mother, it's what she knew and always told me, there's no difference between the spirit and the body. It's the same thing. You just have to accept it. It's a continuum. And of course she's right. Gipsies know it. Aborigines know it. Lots of people know it and individuals know it. The Irish have a tendency to know these things. I dunno, whatever started me off on that, I can't-

Tom Griffiths: You've obviously mastered, you grappled that, but you felt that you mastered it with books like the Sitters and Conditions of Faith. Conditions of Faith is one of my absolute favourites of your novels and highly recommend that book all of them. But you felt in a way that's when you mastered this cohesion between the current place of the narrative and the interior lives. To me, this glows with the interior lives. And we begin at a moment when Fran is knocked out of kilter by a massive emotional event in her life which follows, which explained just at the end of the chapter that you read, she returns to her life in Victoria. Nothing feels the same. She's living on a farm near Newstead in the gold fields, Victorian gold fields. She has her husband, her two children, and we learn about, as she is reflecting on how she sees her life in you as she goes to cell 16 and sees everything there differently, we are living her life with her aren't we? As her interior life is churning away. And that's so charismatic, I think about the novel and your ability as a writer to bring that to the fore, not in any way that is rushing us. We have time we to think with her through that.

Alex Miller: Yeah, I mean the event you're talking to, it's talking about is that event that many of us have had, which is of becoming aware of our creative lives. That it's not just that there is a whole space that's not been explored by us. I mean, that's what she understands, that she sees that there's another her a bigger well, nothing really belongs to her. It belongs to- her family is very demanding. I mean, I've seen that with Steph working at a university, being in charge of a department and of having two children growing up. So okay, there's a good model. Strangely enough, it was a management department, so I don't know the coincidences, they're massive. And it was at this same place but still. It's all made up. And we don't make anything up accurate. Observation is the source of all we write. It better be if it's not, you can feel it. You can feel when it's inauthentic. But she senses something new that belongs just to her. She becomes aware of her creative inner life. And the title actually of the story, it comes towards the very end of the book when a woman who helps her, a woman who becomes her close friend, who to some extent is based on Sylvia Martin's hero, heroine, whatever, in that book of Sylvia's Ink In Her Veins. And when I read it, I wrote about it and then Sylvia wrote to me, and then we developed this terrific friendship and the daughter of, what was her name?

Tom Griffiths: Valerie Summers?

Alex Miller: Yeah, that's in the book. That's the fictional person. Yeah, Valerie. But what's the name of the real person?

Tom Griffiths: Oh, you are thinking of Eileen Palmer.

Alex Miller: Eileen Palmer, the daughter of Netty and Vance Palmer. They had a daughter who spent quite a lot of her time in lunatic asylums, wasn't actually called lunatic asylum in her time. It was called something gentler. And again, it was this sort of gentling of the situation. Did it change anything? Ask someone who was there. It's like when I go overseas and give a talk, so somebody say in China, someone always likes to ask the question, is Australia still racist after the you know? And I said,don't ask me. I'm a member of the ruling culture. I'm a white man. I wouldn't know whether it's racist or not. Ask my Chinese friends, ask my Aboriginal friends. They'll tell you. No question. Fully racist. Yes. And it is racist, sexist, ageist.

Wait till you get to ageing, you get to the ageist stuff. Ageism doesn't need to be apologised for. We haven't kind of acknowledged that yet. But you do cop at 86 now. So that's age, isn't it? I'm old and being old is fine by me. When I turned 80, I said, now I'm in the death zone. But people didn't like that so much. I thought it was a bit in your face. Well, I said, look, this is when we die. We die in our eighties. Most of us. A few people sneak over into 90, but they're not much good. Really? Are they? There's, there's the odd one who's still got like Kissinger. He's on a book tour at the moment. He's 99. And it's a good book. My son read it and said it was a good book. So I stopped calling it the death zone and called it the last chapter. But that was just a bit too almost biblical, isn't it?

Tom Griffiths: We're going to invite some questions from the audience in a moment. I just wanted to say that to me, the book resolves in a very satisfying way. There's a lot of, there are pulses of joy in this book. There's contentment, there's intensity of feeling both of concern but also of pleasure. And it felt to me a happy book in the end, which surprised me. Do you think it's a happy book?

Alex Miller: Surprised me too. Some of my endings have been invented by Stephanie. Don't kill the girl. I said I'm not killing her. I'm trying to explore this subject, the stuff, it's not me. I've got to find the right. Just don't kill her. And

Tom Griffiths: We should go to questions. I know we don't have a lot of time left, but should we invite some questions from the audience? We have some roving mics. And if you can wait till you've got the microphone to ask your question.

Alex Miller: And if you haven't got any questions, make one up. Is your washing machine working okay this week, how to fix it is a question.

Audience member 1: Hello. Thank you very much Alex and Tom for a very interesting discussion. You might've almost answered my question just now, but anyway, at the beginning of the talk you said something about that you want to head to your, it's a journey to the ending. So my question is about the crafting. Do you know where you're going or do the characters lead you? A lot of authors say that they don't have a lot of control about the characters. They sort of really become something that you are just writing their voice. So do you know where they're going?

Alex Miller: No. I mean, yeah, occasionally you do. And maybe that's sort of why you wrote the book to get to that point. And then you wonder, can I ever get to that point with these people? And you discover that yes, you can or you can't. I mean it's kind of a discovery in a way, isn't it? And I don't plot books because I feel plotting is sort of blocking off. I'm probably a bit of a nutcase myself really. I should be put away or will be soon. Don't worry. And it's kind of closing off other options that you haven't thought of. In a sense. If you're having a plot that's going to turn the thing there because you want to get to there and to get to there, you've got to go to there to get there type of thing. So I don't do that because it seems to me to be- Okay, so it's reassuring I suppose if you just want to get to there, but that's not really what I want to do.

I remember my very first book was the Tillington Knot. It didn't get published first, but it was my first book. And I remember coming out of the study where I was working and that was to be a big double ended book. The second half was going to be set in Australia, but it didn't get written. It got half written, but it didn't in the end get written because I'm sitting there writing and I suddenly realised this story, this is finished, this story is ended, just ended then. And I went out to the kitchen where Steph was working at cooking or something like that, or ironing or something before I took over my own ironing. Well, I used to iron before I met her and I said, it's finished. And she said, no, it's not. What about the other half? And I said, the other half doesn't exist, it's finished.

She said, what nonsense. She'd learned a bit since then about writing and I have too. But you know it's making, getting the story together, finding out what it was and being surprised and excited. I know I should go go for walk and you're walking up a hill somewhere, bit out of breath or something like that and you suddenly stop and go, 'I know' you can't wait to get home in case you forget the resolution of something has occurred and you can see it there and you're not going to reject it. You're going to keep it. You're going to deal with it. This is just as true of fiction and nonfiction that overlap what you're talking about. I mean your book on Slicing the Silence, the Antarctic, it's full of that sort of, you've never been there before. I mean you've read about it, you've done your work, but there's a photo of you sitting on the ice actually grinning. And I see you sitting there grinning with the fact that you've realised this is what this is all about, going to the ice. And it's that kind of realisation, which is such a huge delight. It doesn't last that long. Of course, about as long as a really good whiskey lasts if you enjoy that kind of thing and are prepared to put up with a tummy ache afterwards as some of us are.

Tom Griffiths: I think you're right. I think fiction and history share a great deal. And one of them is one, the things they share is this feeling that you are exploring a story and you don't necessarily know the end of it. Historians don't always know how it turned out because there's much there that remains to be discovered. And your characters have a power as well. They do. They wielded over you. Yeah. Are there other questions? Yes.

Audience member 2: Thanks Alex. Thanks Alex. And thanks Tom. Alex, your novels are always so visually evocative, the landscapes, the facts. You can see things. I'm just intrigued that for this novel, the cover is not, thank God, a Getty's image. It's painting by an Australian painter who lives in the same area as you do. And since David moved up into gold fields, I think his landscape painting has changed. It's darker in many ways. I'm just wondering why you chose a painting by that particular painter. Because the goldfields landscape in Victoria, for people that dunno but is a deeply disrupted landscape. It's got all sorts of evidence of movement and human interference, and it's a haunting land haunted landscape in some ways. I was wondering why you chose David Moore's painting and whether that landscape that you now live in or drive through a lot has actually come into the writing of this particular book.

Alex Miller: Thanks, Marick. My publisher sends a few examples of what they've been talking about as a possible cover. The areas they're thinking about, we think about maybe we'll do something this, something like this. And she sent two, Annette Barlows, my publisher, thank God. Over 22, 23 years we've been together, which is unusual in Australia and anywhere in the world as a matter of fact. So we have a great friendship. And I will answer your question. What was it? Oh right. Sorry. Sorry. The artist is David Moore and we know him, Stephen and I know him, know him well. Marick knows him. Tom knows him. We all know him. It's just a coincident thing. We didn't try and organise it, but she sent us a couple of examples of what they might do. One of them was that painting and we both said straight away, yeah, that's it.

And then we looked at her, isn't it David Moore is very much like him. And then she said, you may know this artist. So she in a sense chose it, 50% of it because we could have chosen the other one. We actually, the other one was also by David Moore, but it was a sort of orangey one. And I know it just didn't feel right. So it chose us. And then very generously and wonderfully, which is the kind of thing Alan and Unwin have done for me. We've had a wonderful relationship and that is they bought the painting and gave it to us. So we hung it up at home. And David's,-

Audience member 3:

The landscape affect you to some degree. It certainly does. David,

Alex Miller: Did it affect me? Infect me. You want me to say yes? Landscape does, yeah, affect us and infect, I suppose. What do you mean infect? Infect should associate with disease. Isn't it?

Audience member 3: Something you can't get rid of.

Alex Miller: Something you can't get rid of. Like bunions. Yeah, yeah. Okay. Yeah. Yeah.

Tom Griffiths: Another kind of haunting. Well, I mean I think the farm where Fran and Tom and Little Tommy and Margie live is vividly evoked, very deathly evoked. And it's full of the spirits of the ancient springs. You can see the creek running the pool of water where Fran goes to bathe and to reflect literally about things where Tommy plays the neighbour on the ridge. Who-

Alex Miller: Old lady on the ridge. Yeah.

Tom Griffiths: I mean, yes. Who becomes an important character even though she doesn't drift into the centre of the narrative often. She's a very powerful figure. But yes, it seemed to be creatures of the landscape. She's born there. She knows no other landscape. She will not leave that place. Young Tommy age 10 decides he's going to inherit her farm. She seems happy with this one. Gets a strong feeling. I think as in all your novels, that the landscape is there working in mysterious ways. It's one of those hauntings, one of those sources of spirits. And those ancient volcanic springs seem to be coming out to the surface. Well, they are

Alex Miller: All sorts. I mean they are

Tom Griffiths: Surprising ways

Alex Miller: That particular creek its origins are in. So I was told beneath the volcanoes, which draw water up, and you might know, and I'm sure you do, probably more immediately than I do, but say for example, if you go to a big hill like that, that's where you're lucky to find water up on the top of the hill. I dunno how it occurs, but there's some sort of convection goes on and the springs tend to be there rather than down the bottom. You'd think they'd be down the bottom, but they tend to have their origins up here somewhere. And I think it's something to do with the sort of pressure, isn't it? Is it any hydrologists here would know? Yes. It's actually the pressure from beneath the water. It's called convection actually.

Tom Griffiths: Yes. But I think one of the things about where the farm is situated is it's a kind of meeting place between the volcanic country of the western plains and the upside down country of the alluvial minds. And you seem to evoke that transition zone. I feel beautifully in the novel.

Alex Miller: You bring a lot of that to it, I think. Well,

Tom Griffiths: You provide the means. That's the thing. That's the beauty of a novel, isn't it? That where I began by saying, you create these spaces for reflection, but you provide the sources upon which we can make these connections. And that's the delicacy with which you do that. The softness, the gentleness with which you provide these little bits of evidence, stories, characters, a bit of detail, a sacred detail, which you're such a wonderful custodian of bringing it together for us to find what we want to find to some extent.

Alex Miller: Put that in writing. We'll have in the record then. Thanks, Tom. You're a wonderful reader though. That's the thing, isn't it? We make our own books when we read them to, some people read War and Peace and think, what was that about? And others fortunately don't.

Tom Griffiths: Well, we have to draw to a close. And so I know we all want to thank you for your wonderful writing as a whole, Alex. And we've journeyed through a number of your other earlier novels, but we are very happy to be with you here today in the wonderful National Library of Australia, which we adore and here in Canberra to celebrate.

Alex Miller: He said earlier that when he was off guard, that this building makes living in Canberra possible.

Tom Griffiths: If I might amend that slightly

Alex Miller: Slightly.

Tom Griffiths: It's a reason alone to live in Canberra. Okay.

Alex Miller: That's it. Yeah. It's a reason alone.

Tom Griffiths: And I stand absolutely by that. There is so many other reasons to live in Canberra, but this alone, this place alone, is reason enough to live in Canberra. That's, I lived here for 22 years. I've now moved back to Victoria. But I always felt this was the heart. It is the heart of the national capital. And we are so lucky to meet here and we really, it's a great pleasure to celebrate this new novel of yours, Alex. Congratulations.

Alex Miller: Thanks Tom, thank you very much. Thank you.

Cathie Oates: I have to say, that's going to be an incredibly hard act to follow. You're here on a very special day though for the library. I hope you realise we're having our valves replaced on the roof and the copper has arrived today. So that's auspicious, isn't it? I'm personally, I'm never going to forget the idea of the trampoline of and for ideas. Thank you for such a wonderful conversation that took us to the heart and the spirit, the mind, and the landscape. I hope you can all join us now in the foyer where the presenters have kindly offered to sign some of their books. And please join me again in actually thanking Alex Miller and Tom Griffiths. Thank you very much.

In a discussion facilitated by Tom Griffiths, Alex Miller will be talking about his latest book, A Brief Affair.

Described as 'hauntingly beautiful', A Brief Affair is a novel about storytelling, truths and love. From the bustling streets of China, to the ominous Cell 16 in an old asylum building, to the familiar sounds and sight of galahs flying over a Victorian farm, A Brief Affair is a tender love story.

Content warning: this episode contains mild coarse language.

About the Book

On the face of it, Dr Frances Egan is a woman who has it all - a loving family and a fine career - until a brief, perfect affair reveals to her an imaginative dimension to her life that is wholly her own.

Fran finds the courage and the inspiration to risk everything and change her direction at the age of 42. This newfound understanding of herself is fortified by the discovery of a long-forgotten diary from the asylum and the story it reveals.

Written with humour, sensitivity and the wisdom for which Miller's work is famous, this exquisitely compassionate novel explores the interior life and the dangerous navigation of love in all its forms.

About Alex Miller

Alex Miller was born in South London. As a boy he worked in the west country of England before travelling alone to Australia at age 16. He studied history and literature at Melbourne University. A Brief Affair is his fifteenth book. He is the award-winning author of 13 novels, one biography and one collection of essays and stories and has been published internationally and widely in translation. He is twice winner of Australia’s premier literary prize, the Miles Franklin Literary Award, first in 1992 for The Ancestor Game and again in 2003 for Journey to the Stone Country.

About Tom Griffiths

Tom Griffiths is a historian whose books and essays have won prizes in literature, history, science, politics and journalism. His books include Hunters and Collectors, Forests of Ash: An Environmental History, Slicing the Silence: Voyaging to Antarctica, Living with Fire and The Art of Time Travel: Historians and their Craft. He writes for Inside Story, Griffith Review, Meanjin and Australian Book Review, and is Emeritus Professor of History at the Australian National University. He has lived in the Macedon Ranges since 2018.