Due to scheduled maintenance, the National Library’s online services will be unavailable between 8pm on Saturday 7 December and 11am on Sunday 8 December (AEDT). Find out more.

In most homes in Australia, you will find a bookcase, a mantelpiece or a shelf with a display of family photographs. These small intimate galleries chronicle the individuals, both young and old, who populate the family tree. Sometimes the images reach back two or three generations, depicting siblings, parents and grandparents.

One of them may be of a relative who embarked on a long and difficult journey to Australia. This treasured portrait testifies to how that journey helped make possible the life the family has today. When you look at the picture of an ancestor, someone who may have spoken a different language, eaten different food and worn different clothes, it invites you to wonder why they decided to leave their home, and what it was like for them to arrive in a strange new country. What were the hopes and fears that motivated them to recast their lives in such a dramatic way?

Stories of migration are very much part of our national experience. The most recent Australian Census, conducted in 2021, tells us that more than half of Australians have at least one parent born overseas or were themselves born overseas. Coming from all parts of the globe, these migrants help make Australia one of the most diverse nations in the world. Today it is a favourite pastime for Australians to compare their backgrounds and celebrate their connection to a country or continent far away.

On this page:

- Never ceded

- The colonies

- Gold and exploration

- An outpost of the British race

- Becoming Australian

- Refugees

Never ceded

Exploring the history of migration to Australia starts with an important fact. First Australians have lived on this continent for at least 65,000 years. They did not cede the land that the British claimed, and they continue to assert their sovereignty. When Governor Arthur Phillip arrived on Gadigal Country with the First Fleet of 11 ships on 26 January 1788, he did not have the permission of the Gadigal people, that of any other peoples of the Eora Nation, to build a settlement at Sydney Cove.

The process of colonisation, which has unfolded ever since, resulted in the dispossession of the Traditional Owners from their land. First Australians resisted the British, but in most instances they were pushed off their Country. Disease, violence and coercion, and competition for resources wrought terrible damage, but Indigenous nations survived to reclaim lands and waterways, and today their cultures and languages are often resurgent.

The colonies

The British occupation of Australia was part of a larger pattern of European colonisation across the globe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The European powers were searching for new territory to exploit, and the reports of explorers, especially James Cook following his expedition along the east coast of Australia in 1770, indicated that this was a land that might be successfully occupied.

The first convicts, sailors and soldiers who came to Australia had little choice in the matter. After the rebellion of British colonies in nNorth America, the imperial government sought to address the problem of overflowing prisons at home, and to stake a strategic claim in the Pacific region, by establishing a colony at Botany Bay. When Phillip arrived with the First Fleet in January 1788, he preferred Port Jackson — soon to become known as Sydney — as a more suitable site. As the colony grew, and profits from trade within the British Empire accrued, more people came.

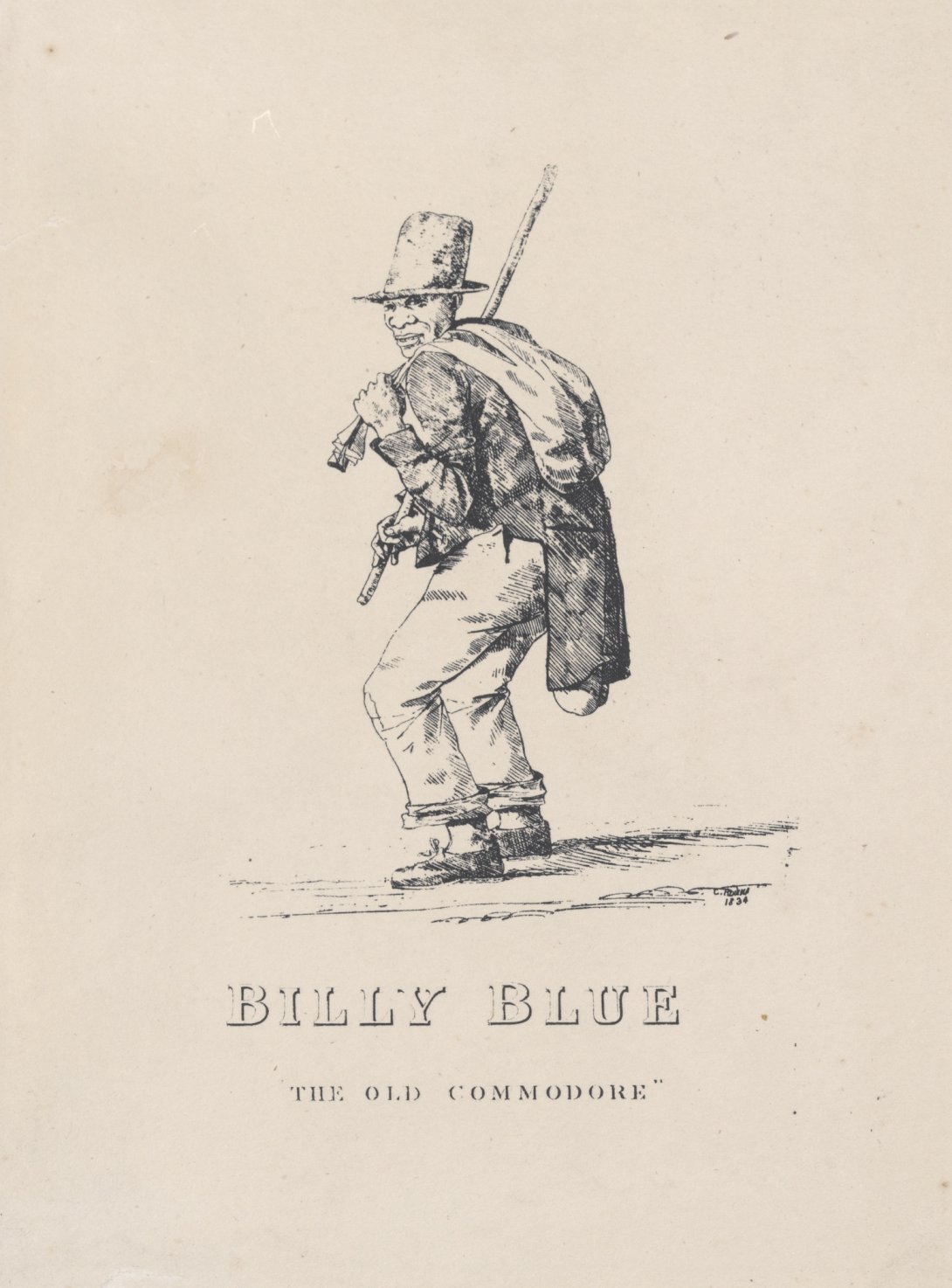

The convicts, and the guards and officials who accompanied them, were predominantly British, but there were exceptions, such as William Blue, an African -American originally from New York. Blue was transported to Sydney in 1801 for stealing raw sugar. After finishing his sentence, he worked as a waterman, and in 1811 Governor Lachlan Macquarie appointed him harbour watchman and constable. Blue eventually became a well-known Sydney identity, nicknamed ‘the Old Commodore’. His journey from convict to valued member of the community was a story that was not uncommon in early Sydney. Many convicts eventually made the transition from prisoner of the Crown to landowning settler or entrepreneur.

As such, the Australian colonies became a place where there was potential for a new start. As the colony prospered, the convicts were followed by free settlers who came in search of cheap land and new economic opportunities. Charitable organisations sent young women from workhouses and children from orphanages. The unemployed could apply for assisted passages in the hope that the colonies would provide them with a better future.

Wealthy British investors, with ready access to capital and political influence, were able to take advantage of the opportunities on offer. Products such as whale oil, seal skins and wool offered the promise of rich returns.

In 1840 the end of convict transportation to eastern mainland Australia posed a challenge, as cheap labour was required to exploit the land which had become available. To fill this gap, indentured labour was imported from India and China. Pacific islanders were brought in — sometimes without their consent — to work on plantations in the tropical north, mainly growing sugar.

Gold and exploration

The goldrushes of the 1850s led to a population explosion as people migrated to south-eastern Australia from all over the globe, lured by the prospect of wealth. This set the scene for further unrest, based on class, race and access to land, just when the colonies were beginning to govern themselves. Unrest erupted on the Ballarat goldfields in what famously became known as the Eureka Stockade uprising of 3 December 1854. Anti-Chinese violence occurred on the goldfields in New South Wales and Victoria.

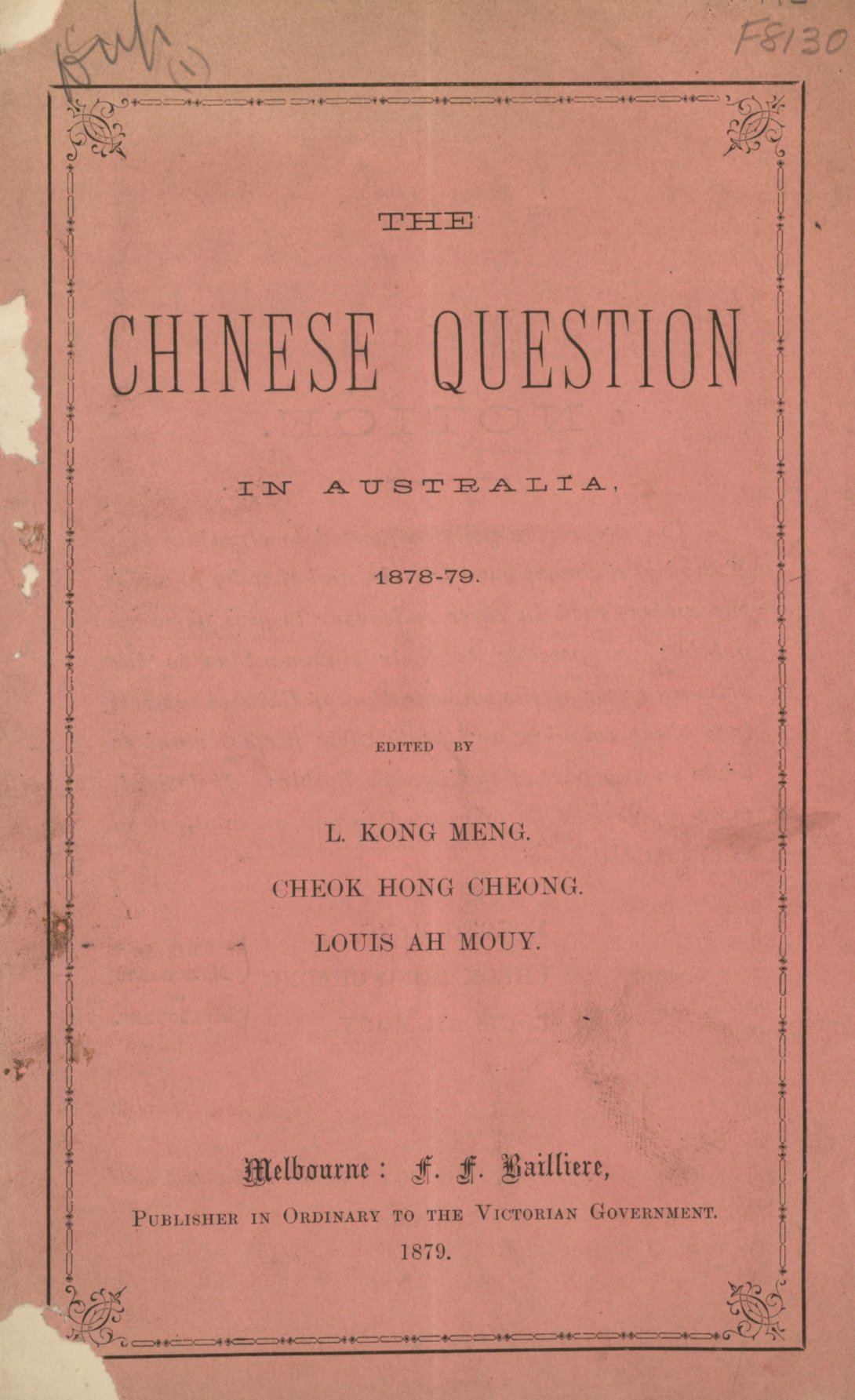

Colonial governments imposed various anti-Chinese laws, including the immigration poll tax introduced in Victoria (1855), South Australia (1857) and NSW (1861) and the Chinese residence tax in Victoria (1857). Chinese miners protested the laws via petitions and sustained avoidance of the taxes and, by 1867, they had all been repealed.;

South Asians (referred to as ‘Afghans’), with their expertise as cameleers, migrated to assist in opening up the centre of the continent to more Europeans from the 1860s, thereby further contributing to the dispossession of the First Australians.

An outpost of the British empire

There was a revival of anti-Chinese sentiment and legislation in 1878, in response to Chinese migration to the Palmer River goldfields in northern Queensland, the presence of Chinese labour on merchant shipping and campaigning by politicians and union leaders. The motivation for anti-Chinese agitation was both racial, with widespread fear and prejudice against ‘coloured’ people, and economic, with miners and unions wanting to protect jobs and working conditions.

With the coming of Federation in 1901, this desire for a British Australia was expressed in the ‘White Australia policy’, which was implemented through legislation such as the Immigration Restriction Act 1901, which created the machinery for an arbitrary dictation test. Between 1901 and 1958, migrants could be asked to write 50 words in any European language, as dictated by an immigration officer. After 1905, the officer could choose any language. This made it easy to fail an applicant if they were from an ‘undesirable’ country, had a criminal record, medical issues or were thought to be ‘morally unfit’. The new federal parliament passed legislation that enforced the repatriation of Pacific islanders who had been brought to work on sugar plantations. The new Australian Constitution’s race powers excluded the making of laws for First Australians, responsibility for whom remained exclusively with the six states until the Northern Territory passed from South Australia to the Commonwealth in 1911.

The First World War temporarily halted the flow of migrants to Australia, but it soon regathered pace in the 1920s. Britain was again targeted for workers, particularly farmers, labourers and domestic servants. More than 300,000 migrants came during the decade, many of them taking advantage of the assisted passages scheme jointly funded by the British and Australian governments. William Hughes, who was prime minister from 1915 until 1923, emphasised Australia’s need to increase its British population to preserve its security; as health and repatriation minister in the 1930s, he popularised the slogan ‘populate or perish’.

In the lead-up to outbreak of the Second World War the Australian Government initially resisted taking Jewish refugees, but eventually relented. More than 5,000 Jewish refugees arrived in 1939.

Becoming Australian

During the Second World War the Australian Government began planning for an expanded immigration program and, in 1945, established the Department of Immigration with Arthur Calwell as its first minister. Calwell travelled to Europe in 1947 and met with the International Refugee Organization. Australia agreed to assist with the resettlement of the millions of people displaced after the war.

By 1954 more than 170,000 of these displaced persons, mainly from the Baltic states, Poland and Eastern Europe, had migrated to Australia. New migrants helped fill Australia’s factories and mines, and they worked on infrastructure projects such as the Snowy Mountains Hydro-electric Scheme.

While the migration intake had been expanded to take people from across Europe there was still a strong focus on attracting British migrants to Australia. In 1945 the Assisted Passage Migration Scheme, popularly known as the ‘Ten Pound Pom’ scheme, allowed British migrants to come to Australia for £10 provided they were under 45 and in good health. The scheme remained in place until 1959.

From the 1950s Australian governments began to slowly dismantle the legislative framework that underpinned the White Australia policy. The Immigration Restriction Act 1901 was superseded by the Migration Act 1958, under which the infamous dictation test was replaced with a system of visas. In 1966 a review of Australia’s migration policy recommended that the assessment of potential migrants focus on their qualifications and suitability to settle, rather than on their race or nationality. As a result, the government began to accept a small number of migrants from Asia.

In 1973 further changes were made, allowing migrants to apply for citizenship after three years of residence, regardless of race. Then immigration minister Al Grassby articulated a new vision of a multicultural Australia in which migrants from diverse cultural backgrounds would be celebrated for their contribution to Australian society. The migrant intake to Australia was becoming more diverse, but there was little Asian immigration until later in the 1970s.

Refugees

The acceptance of refugees has been part of Australia’s migration program since the 1950s. Migrants came from Hungary, after the Soviet repression of the Hungarian Revolution in 1956, and from Czechoslovakia, after the suppression of the ‘Prague Spring’ of 1968. They also came from Southeast Asia after the end of the Vietnam War in 1975. Political troubles and environmental factors like drought causing famines, in South America, Ethiopia and the Middle East also prompted refugees to seek protection in Australia.

Many Chinese students successfully applied to remain in Australia in the wake of the infamous ‘Tiananmen Square massacre’ in 1989. Conflict in the former state of Yugoslavia in the 1990s also led to more refugees being resettled.

Australia’s humanitarian program continues to the present with refugees arriving from Iraq, Syria, Iran, Myanmar, Afghanistan, Democratic Republic of Congo, Burundi, Somalia and Sudan. Today Australia is one of the main countries committed to resettling refugees.

During the 1980s concerns about the level of unemployment led to a reduction in Australia’s migration intake and a shift of focus away from assisted migration towards schemes specifically designed to attract skilled migrants to fill labour and skill shortages. Reuniting families, however, continued to be an important component of Australia’s migration intake.

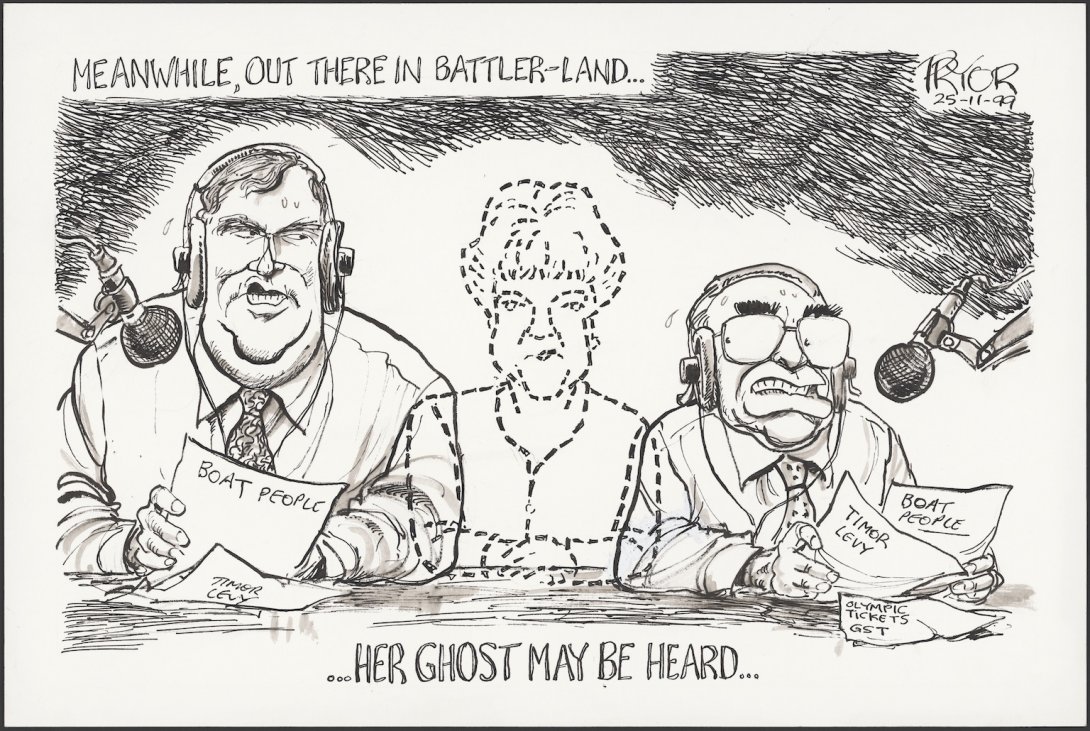

In the 1980s and 1990s migration became a hot political topic in Australia. Community anxiety about the impact of migration — specifically, non-European migration — on social harmony, employment and housing was reflected in increased anti-migrant rhetoric. The celebration of multicultural Australia, which had marked the 1970s, endured alongside debates about Asian and Muslim immigration and border control.

In 2015 the Department of Immigration and Border Protection and the Australian Customs and Border Protection Service were amalgamated. Migrants arriving in Australia today are met by officers of the Australia Border Force, a law enforcement agency.

The history of migration to Australia has been marked by fierce debates about who should come to this country, and who should be allowed to stay. It also comprises many individual stories of those who made the journey to Australia and of their struggle to start a new life. To understand this history, we need to interrogate the evidence that has survived from the past.

The Hopes and Fears exhibition showcases a fascinating selection of these many and varied records from Australia’s migration history, all of which are available at the National Library.