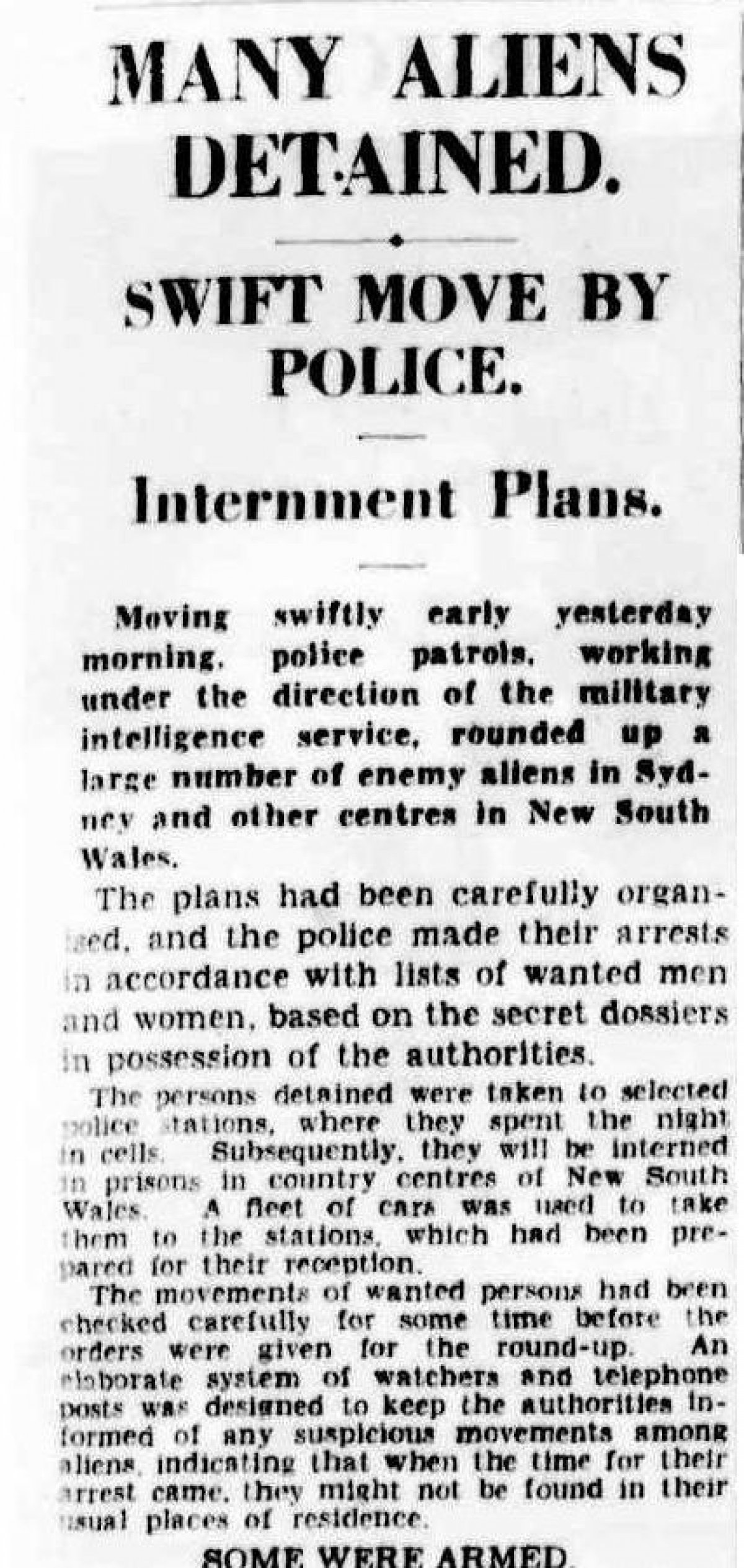

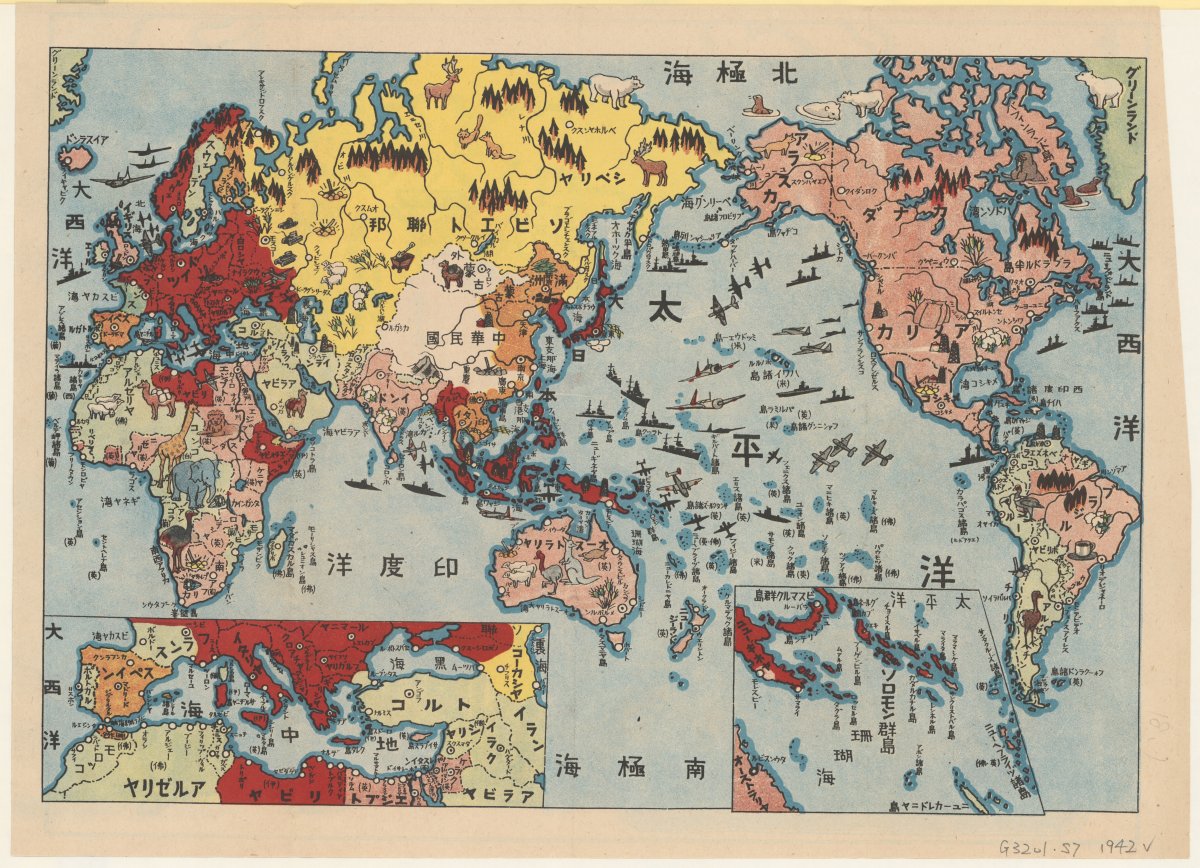

MANY ALIENS DETAINED. (1939, September 5). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 11. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article17631257

As the outbreak of war was announced, police forces around Australia moved swiftly to ensure there were no concerns about security at home. German ‘enemy aliens’—the same term as used in the previous war—were being rounded up, : those who were to be detained were identified from lists prepared before the announcement of the war. Within hours, 257 people had been taken from their homes. Many more would follow.

The Prime Minister’s announcement caused a lot of fear among German communities throughout Australia; the impact of the previous war was still raw in their memories. The early arrests were taken as a clear signal that they would not be given special treatment just because they lived in Australia. Others outside those communities gave voice to the concern that it was not in the national interest to embrace war hysteria and to persecute the innocent. The distinguished Melbourne lawyer and politician Maurice Blackburn was one who spoke out against the curtailment of liberties during World War I, and who now urged calm:

I warn Australians against being provoked into any discrimination against the vast number of people of German extraction in this country.

The legal basis for the internment of civilians in World War II was the National Security Act 1939. Passed by Parliament on 8 September, it came into force the next day. It gave the government of the day powers that were more extensive than those provided by the War Precautions Act 1914 in World War I, as it allowed the Government to issue a series of National Security Regulations that could take the form of internment or a range of other restrictions.

To begin with, at least, the Government resisted the temptation to carry out widespread internment. Pragmatism dictated that a workforce would be needed to keep the economy running, as young Australians followed in their parents’ footsteps and enlisted in the Second Australian Imperial Force (2nd AIF). A carefully targeted internment policy, it was believed, could convince everyone that issues of security were taken care of.

In other ways, too, the events that followed the outbreak of this war echoed the previous one. At first, the instructions issued to the military commands around the country were that internment was:

only to be resorted to when it was considered that other forms of control would not be adequate; there must be a reasonable case against an enemy before he was interned, but membership of Nazi or Fascist organisations was to be considered a prima facie ground for internment.

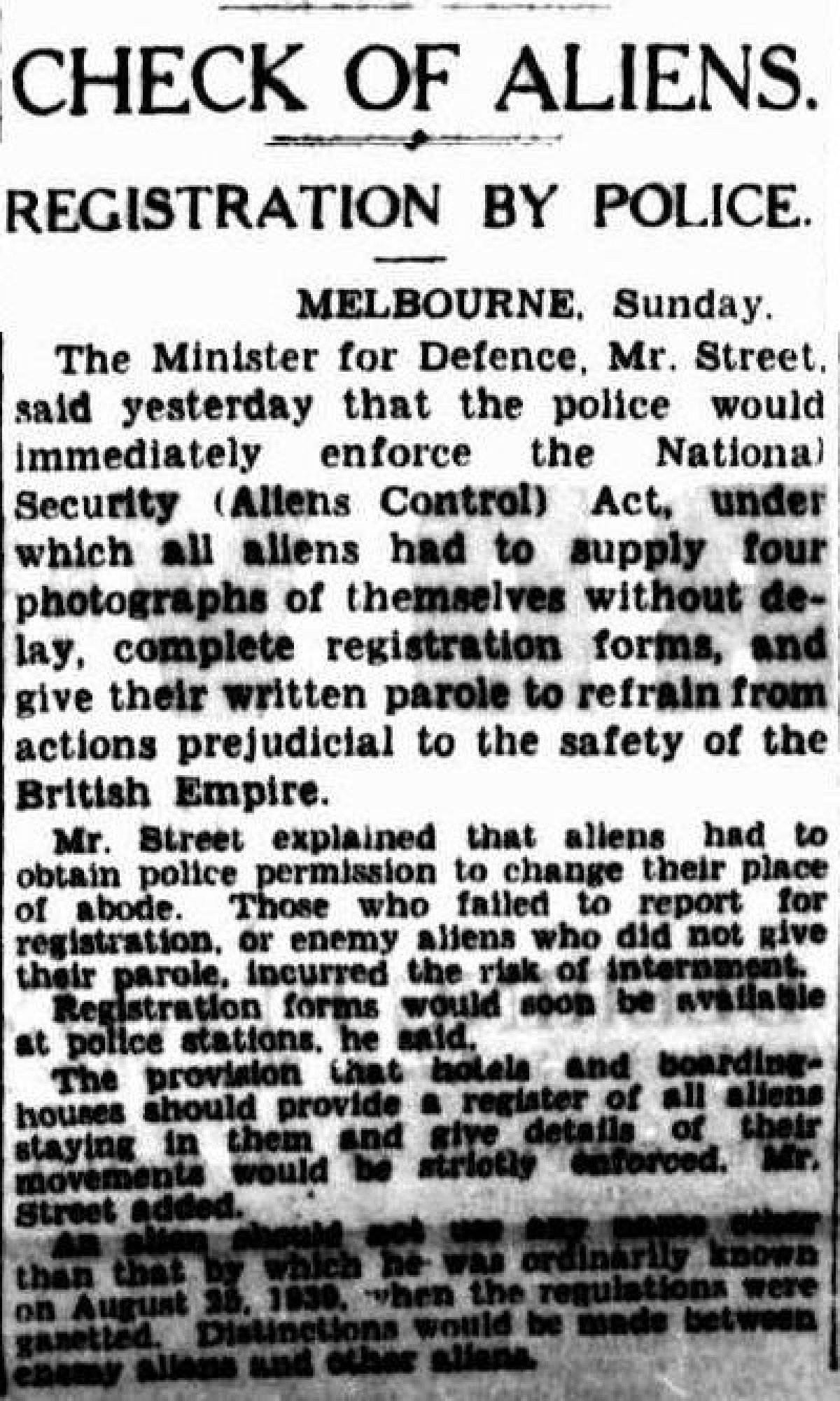

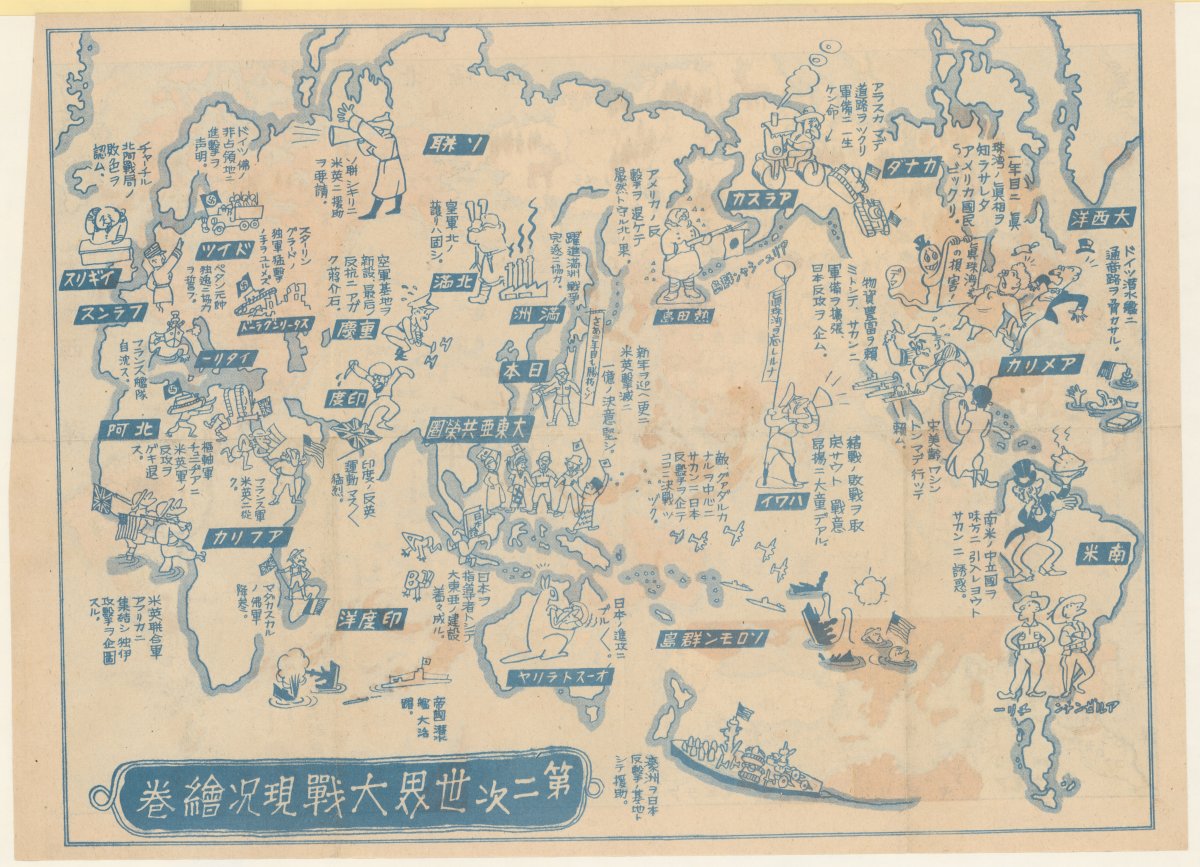

CHECK OF ALIENS. (1939, September 11). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 11. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article17644712

Registration, on the other hand, was widespread, just as it had been in World War I. At their local police stations, ‘aliens’ over the age of 16 had to submit the appropriate forms and agree to report regularly to the Aliens Registration Officers. Non-compliance, as for a generation earlier, could mean arrest or internment. Over time, in this war as in the previous one, restrictions that were applied to those who were not interned grew ever greater. Without a special permit, they could not possess a firearm, a camera, a car, a boat or even a carrier pigeon.

While there were numerous similarities with World War I, there were also some differences that shaped the way Australia approached the issue of domestic security. In World War I, both civilian internees and prisoners of war—members of enemy armed forces captured during or after battle—were labelled Prisoners of War (POWs). In this war, international law demanded that a clear distinction be drawn between the two groups. While the military authorities charged with the care of both populations were obliged to treat them humanely, they would be subjected to different regimes of detention and held in separate places.

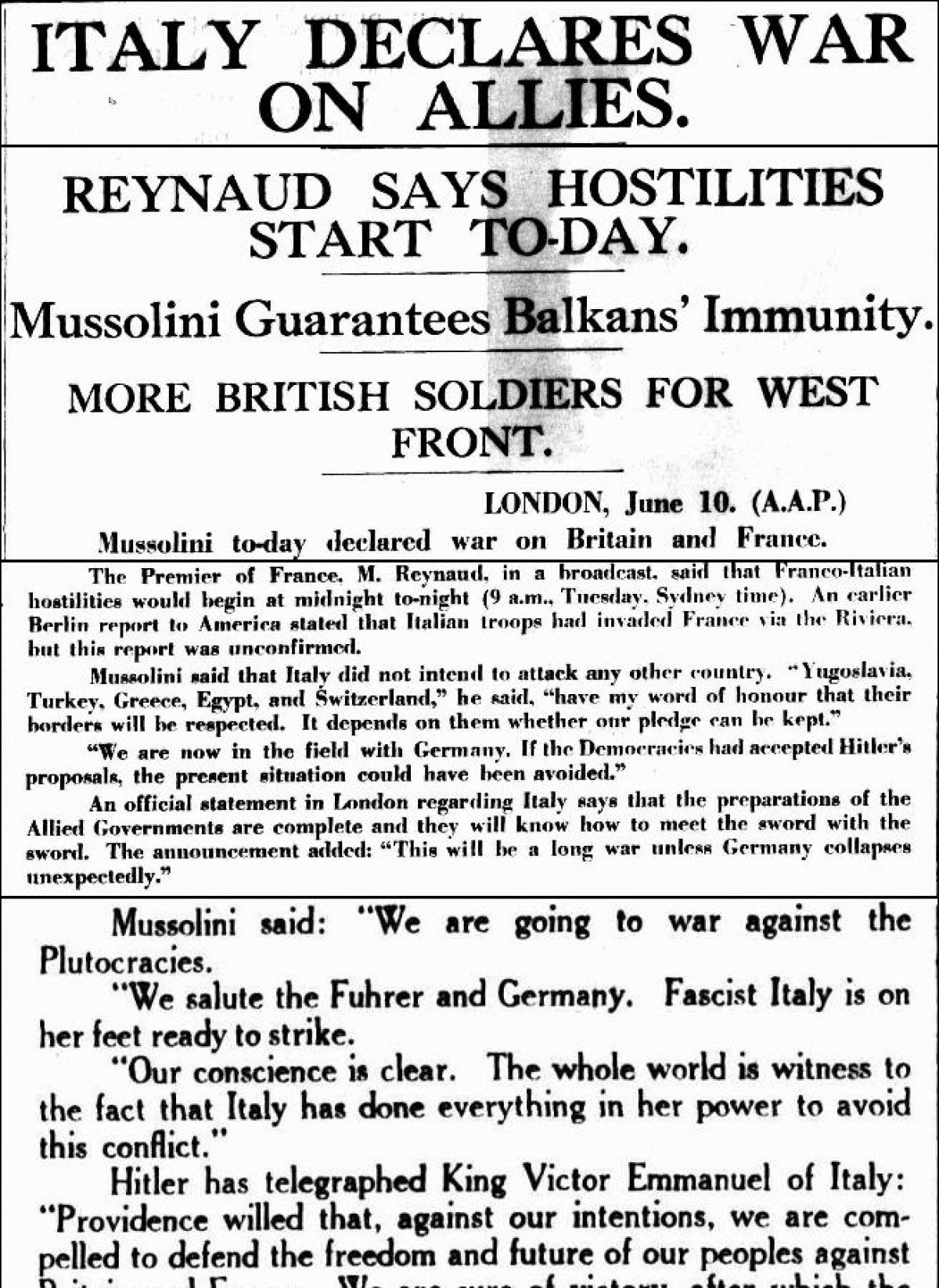

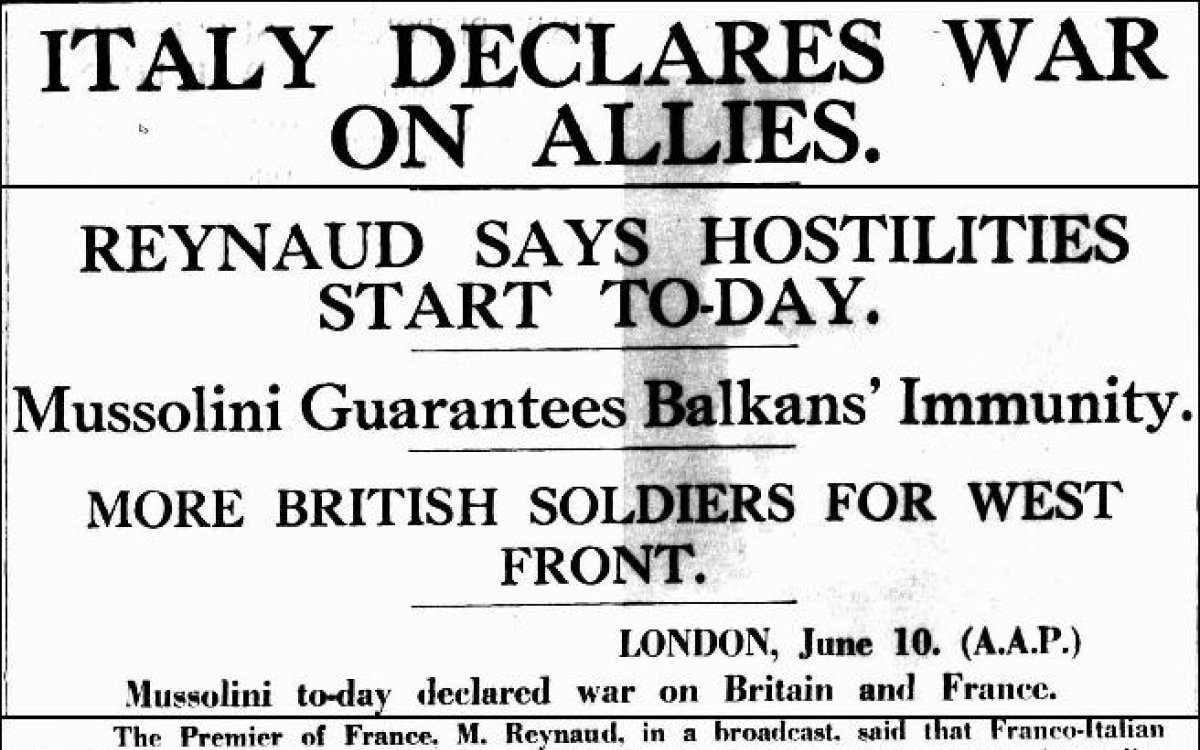

While the Government’s intention in 1939 was to limit internment to a select few, practices changed as the war progressed. Much like a generation earlier, enthusiasm to intern at home matched military fortunes abroad. After months of a Phoney War (when there was little fighting), hostilities exploded in April 1940, when German forces (the Wehrmacht) invaded Denmark and Norway. The following month, the Wehrmacht pushed through the Netherlands and Belgium; in June, France signed an armistice with Germany, and Italy entered the war on Hitler’s side. In Europe, the British seemed to stand alone in resisting the Nazis and, under their new Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, they braced for a battle for their very survival: it was a real and widely accepted prospect that Britain, too, would be invaded. On the other side of the world, rumours of the existence of a ‘fifth column’—a term used to describe people who, it was thought, were seeking to undermine Australia’s war effort, and consisting largely of ‘enemy aliens’ with malicious intent—reached their peak.

ITALY DECLARES WAR ON ALLIES. (1940, June 11). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 - 1954), p. 9. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article17679159

The numbers of Germans interned grew, but they were no longer alone. Mussolini’s entry into the war, on 10 June 1940, triggered the arrests of Italians, using lists prepared in advance by intelligence authorities. In Queensland alone, 103 men were arrested within a day of Italy’s declaration of war, and many more would follow, including women and children. People who thought that being British subjects—whether by birth or naturalisation—would protect them from internment, were disappointed.

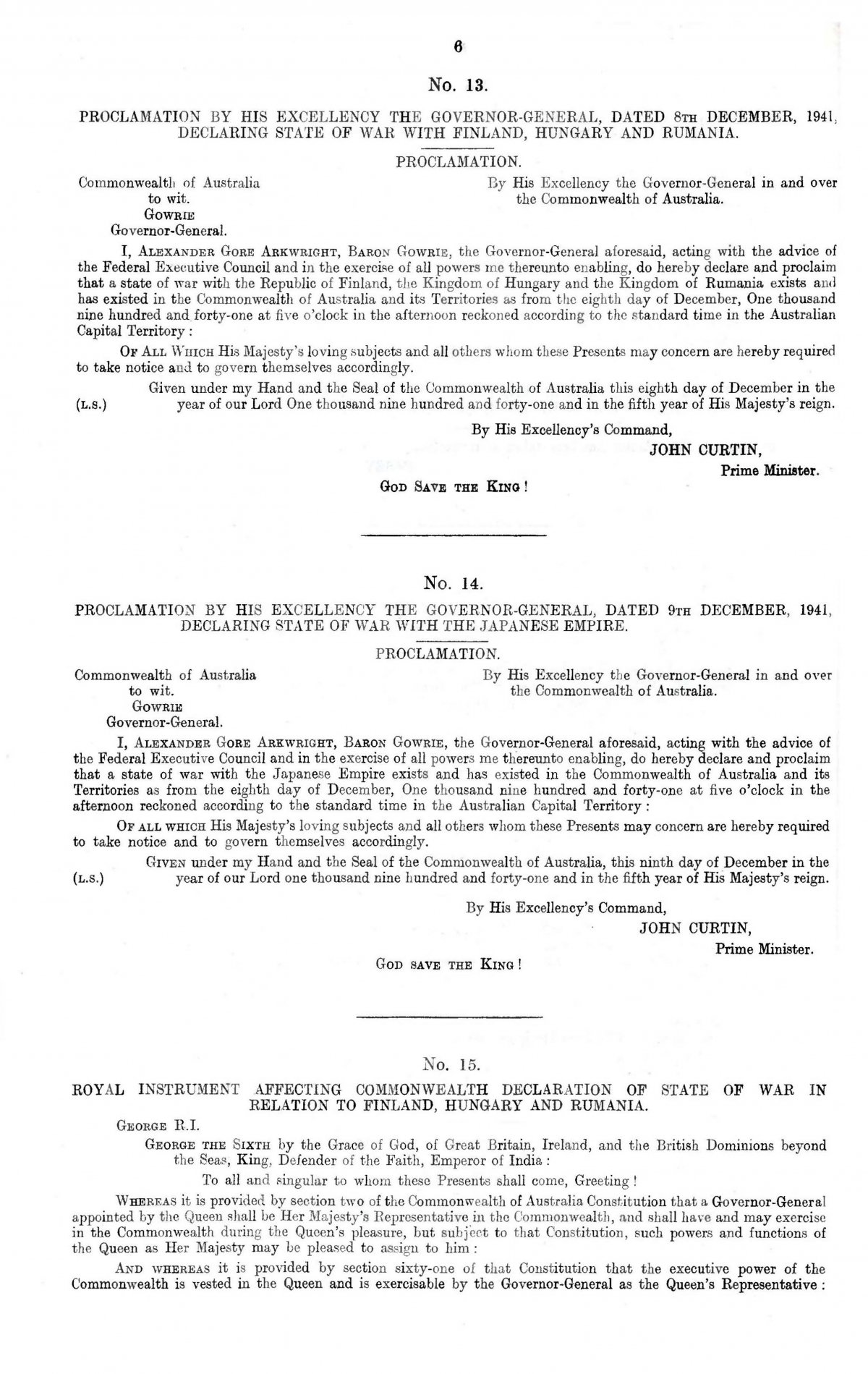

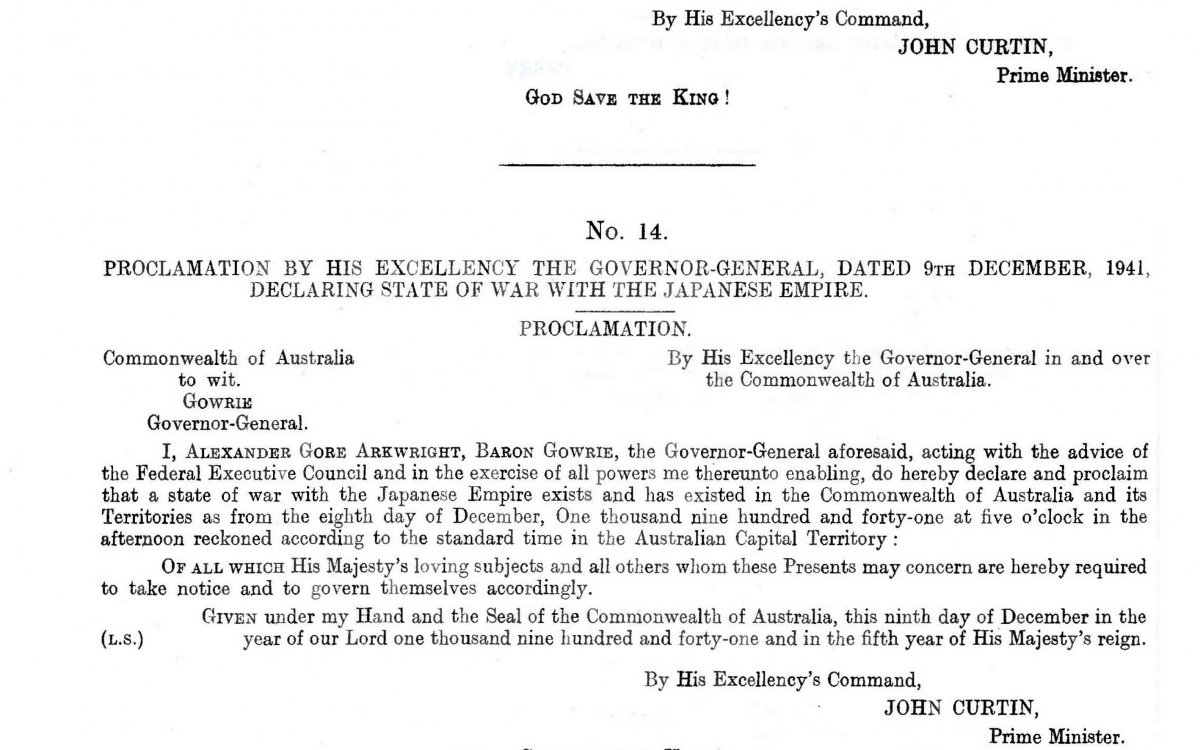

Australia. Parliament. (1941). Declaration of existence of state of war with Finland, Hungary, Rumania and Japan 8th December 1941 : documents relating to procedure of His Majesty's government in the Commonwealth of Australia. Canberra : Printed and published for the Government of the Commonwealth of Australia by L.F. Johnston, Government Printer https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-1928613644

Worse was to follow. While Britain stood firm and avoided a German invasion, the Axis powers—including not just Italy but also Hungary, Rumania (now spelled Romania), Bulgaria and Finland—gained control of the front line from Dunkirk in France to the outskirts of Moscow, and from the coastal plains of Libya to the ports of Norway. Then, with the bombing of Pearl Harbor by the Japanese in December 1941, Japan entered the fighting. A European war became a world war, and Australia felt threatened as never before. With the fall of Singapore in February 1942 and the bombing of Darwin just four days later, Australian anxieties reached fever pitch. Never had the pressure to intern people been so great. Before the war was over, some 12,000 people from many different backgrounds and from many parts of the world had experienced life inside an Australian internment camp.

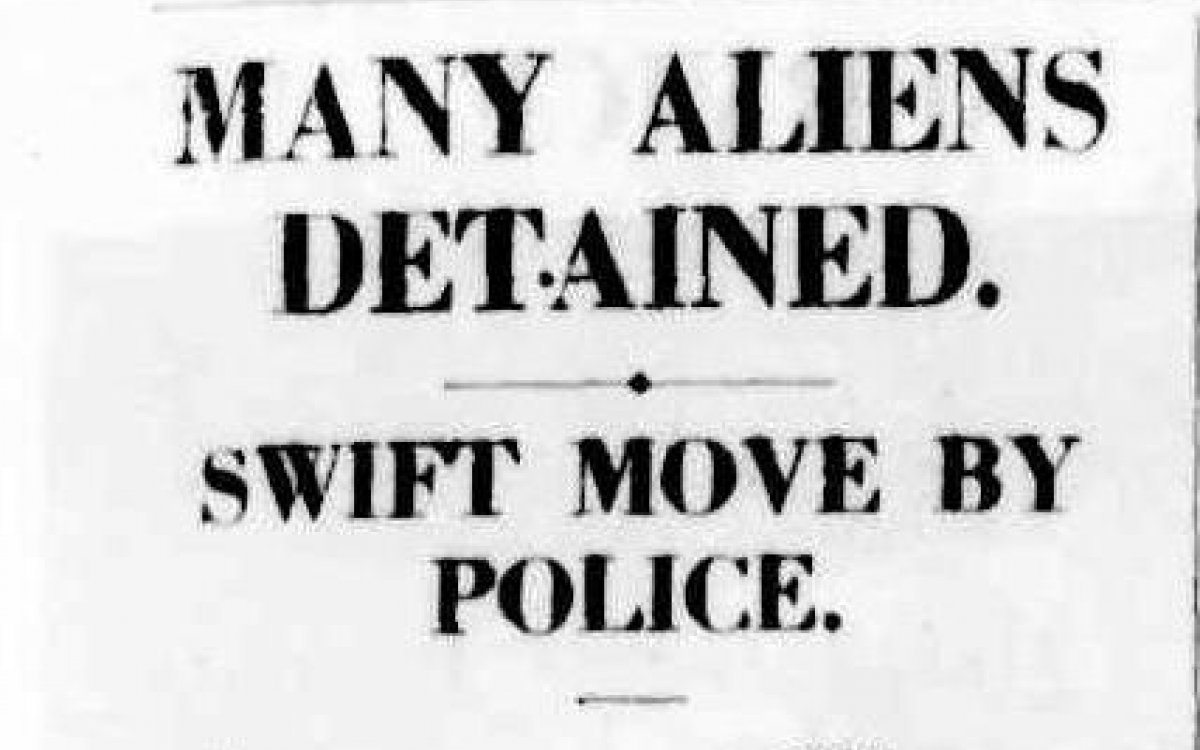

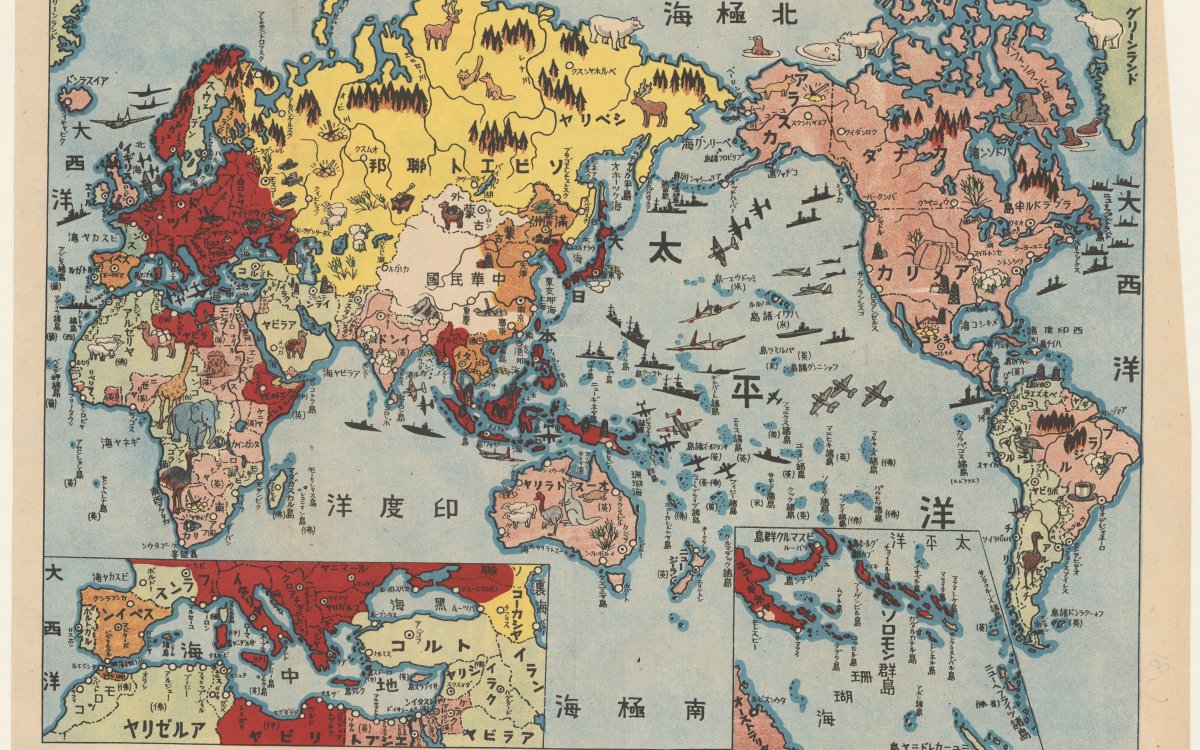

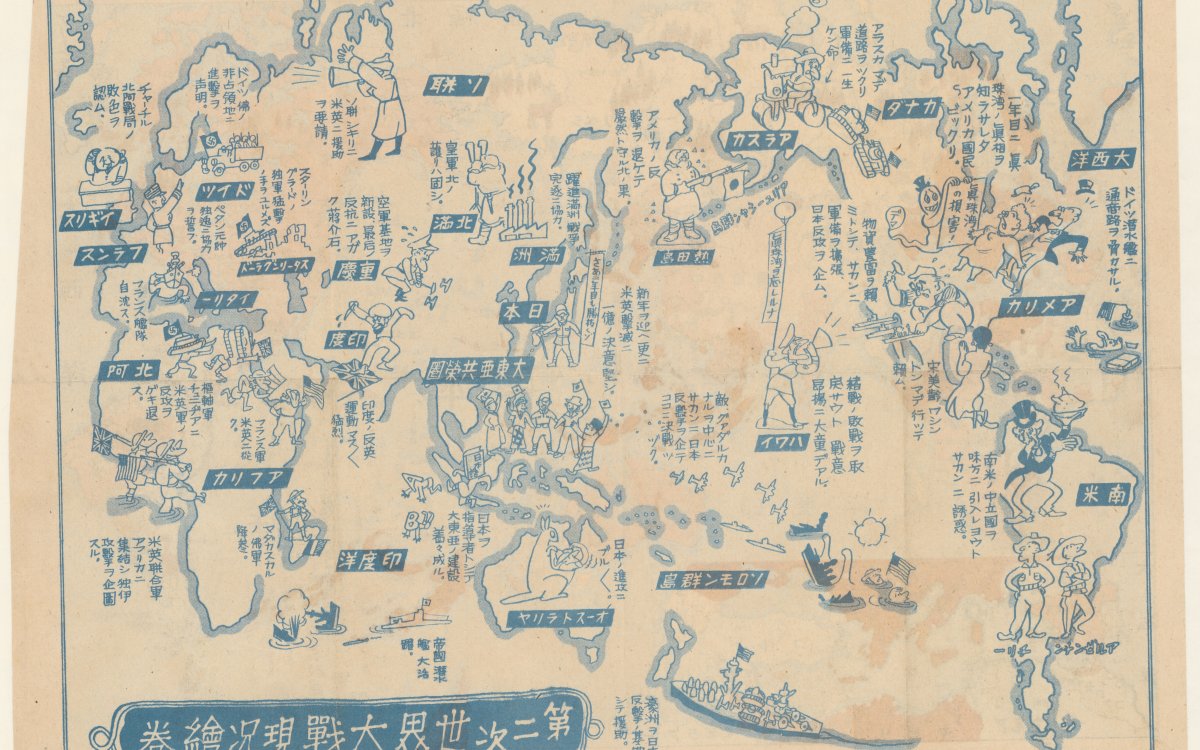

(1942). [Japanese map of World War ll]. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-234704475

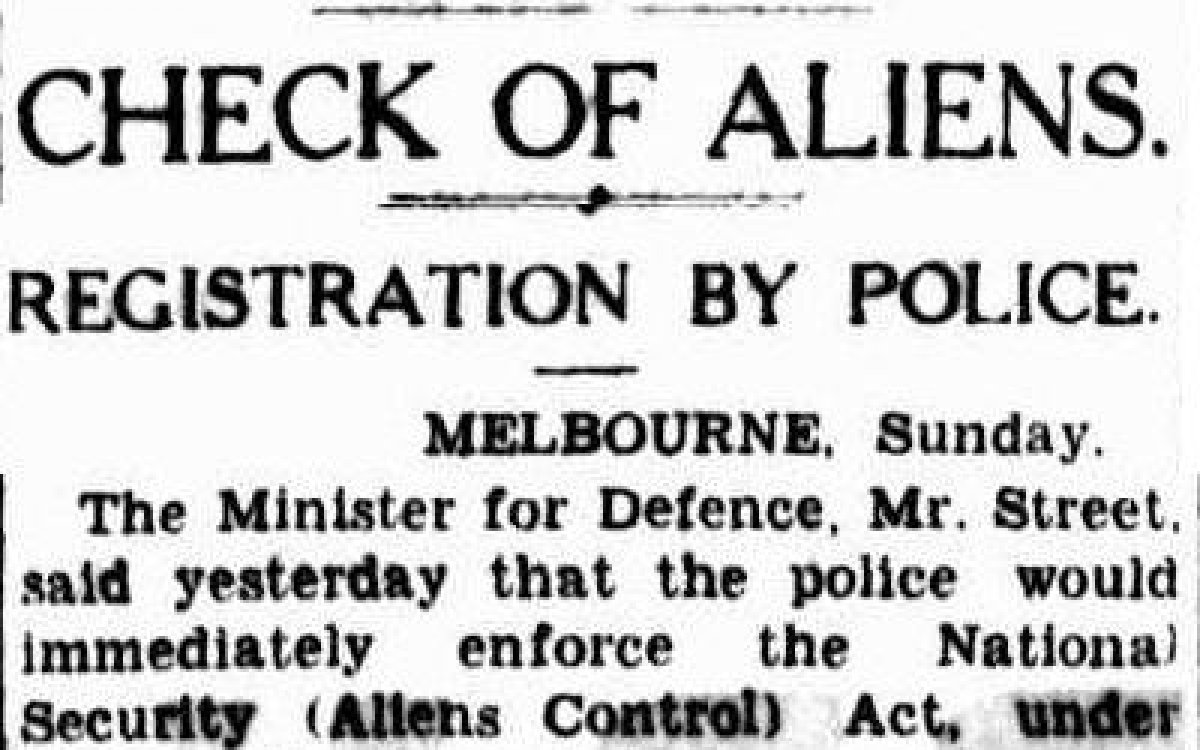

[Japanese map of World War ll]. War ll, Tōkyō: Nobarasha, 1942. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-234704590

Activities

- Ask students to consider the term ‘enemy alien’ or ‘alien’. What kind of imagery is conjured up? Do terms like this have any implications associated with them? Does this type of language help or hinder the spread of panic in the community?

- Looking at the coloured side of the Japanese map, what is the purpose of this map? Who is the intended audience for this map? How would someone in Australia in 1941 feel if they saw this map?

- How do the powers given to the government during World Wars I and II compare with powers given to the governments in Australia in other times of crisis or emergency since World War II?