Due to scheduled maintenance, the National Library’s online services will be unavailable between 8pm on Saturday 7 December and 11am on Sunday 8 December (AEDT). Find out more.

This theme supports the following Content Descriptions for History 7-10 – Year 8 : Medieval Europe and the modern world.

AC9HH8K02

- The roles and relationships of different groups in Medieval, Renaissance, or pre-modern Europe

AC9HH8K03

- A significant event, development, turning point or challenge that contributed to continuity and change in Medieval, Renaissance, or pre-modern Europe

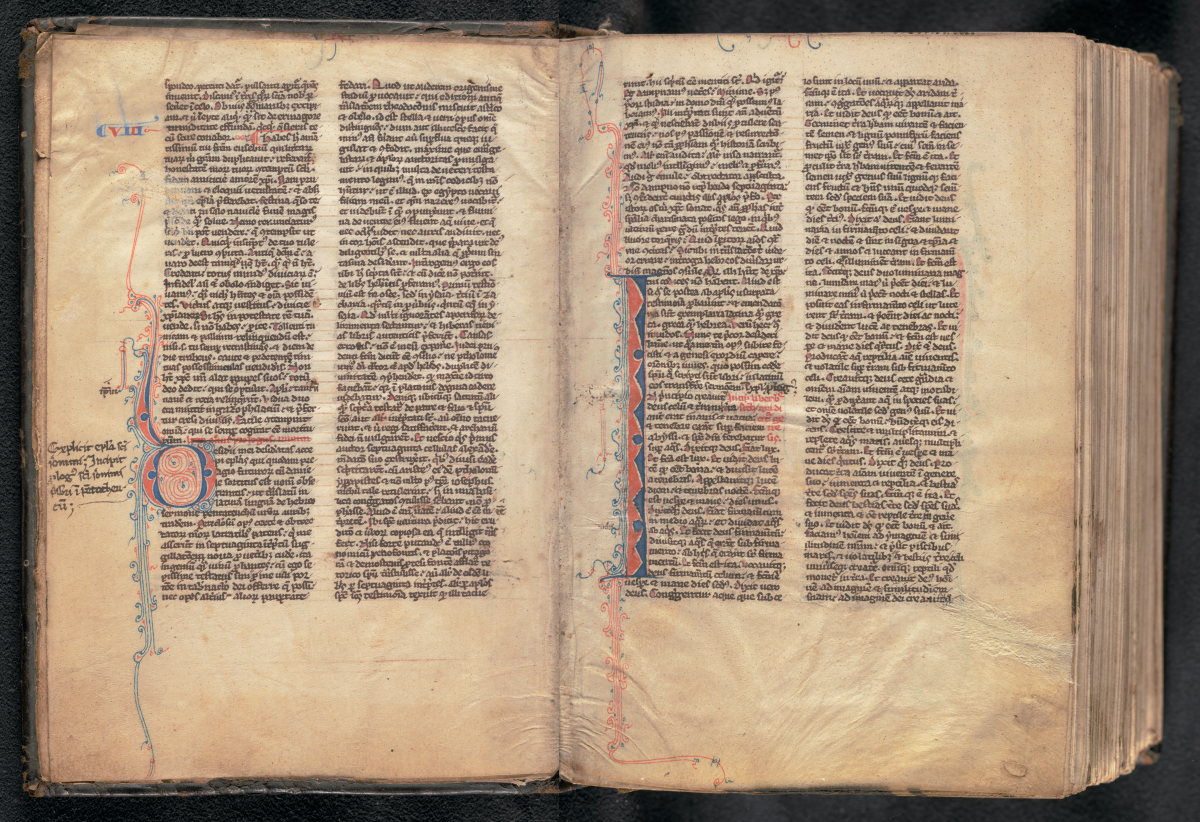

Detail from (1330). Illuminated Psalter, 1330-1350 [manuscript]. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-182166477

(1330). Illuminated Psalter, 1330-1350 [manuscript]. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-182166477

For most of human history beyond living memory, the main way we know what life was like during the Medieval period is from documentary evidence that remains available to us. Documentary evidence includes things like:

- Diaries

- Newspapers

- Official documents

- Letters

- Contracts

- Wills

- Drawings

- Paintings

In modern times:

- Photographs

- Film

These sources can give us a first-hand account of what life was like, what people were doing, what they were thinking or what problems they or their communities faced. It can also tell us things about the society such as the wealth of communities or individuals, the political or social structure and the health of the people.

Throughout most of human history, literacy levels (the ability to read and write) has been very low. Some estimates place Medieval western European literacy levels below 20 per cent of the population; that is, fewer than two people in every ten could read or write. Those who could write were usually those of the upper classes, royalty or the church. This means that there is generally more documentary material relating to the lives of the upper classes, while the lives of everyday people often go unwritten. Historians can piece together information about everyday life, however, through documents like contracts, receipts, church records and even court documents.

Throughout most of human history, literacy levels (the ability to read and write) has been very low. Some estimates place Medieval western European literacy levels below 20 per cent of the population; that is, fewer than two people in every ten could read or write. Those who could write were usually those of the upper classes, royalty or the church. This means that there is generally more documentary material relating to the lives of the upper classes, while the lives of everyday people often go unwritten. Historians can piece together information about everyday life, however, through documents like contracts, receipts, church records and even court documents.

The National Library of Australia holds a rich collection of Medieval manuscripts and early books, both religious and secular, dating from the eleventh century CE through to the Renaissance era. These documents have made their way into the Library’s collection through donations, bequests and purchases. They include items that document political, judicial, religious and economic happenings, mainly in England, but also some from continental Europe.

From these documents we can see snapshots of moments from the lives of people who lived almost a thousand years ago.

A faithful history

The oldest item in the Library’s collection is a small fragment from a book of prayers or a breviary. It was used by someone who was part of the church, perhaps a priest. It dates from the tenth century and is from England. It is only a very small portion of the whole text, but the text is readable with music notes visible. The text is a section of the Bible, taken from the Book of John chapter 8 verses 21–29. Jesus speaks to the people and predicts his own death and says that his actions are the work of God. The musical notation is a gradual, a sung section of a Catholic mass.

MS 4052-Medieval manuscripts and documents from the Nan Kivell calligraphy collection, circa 10th century-1819/Series 2/Item 16/Recto 16. Musico-litergical documents/ Fragment from a missal. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-214214193

As a religious or liturgical text, this document can help us learn what a typical religious service may have been like and how people’s experience of faith has changed since this time.

This document, from about two or three hundred years after the breviary fragment, is also written in Latin. This is another gradual or missal, a guide to performing a religious service. It shows a range of musical chants that would be performed throughout a service. Today, Latin is still an official language of the Vatican City and many Catholic Church services are delivered in Latin or with parts spoken in Latin. With its beginnings in ancient Rome, Latin remained the main language of official documentation and the church in Medieval Europe for many centuries after the fall of Rome. However, the language was gradually changing.

Composite of nla.obj-77869915 and nla.obj-77870458

MS 1097-Clifford collection of manuscripts mainly relating to Roman Catholicism, circa 1250-1915 [manuscript]./Item 3/Folio recto 4., Latin Bible, and Remigius, Interpretationes Nomium Hebraicorum., https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-77870458

MS 1097-Clifford collection of manuscripts mainly relating to Roman Catholicism, circa 1250-1915 [manuscript]./Item 3/Folio verso 3., Latin Bible, and Remigius, Interpretationes Nomium Hebraicorum., https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-77869915

This example from the early sixteenth century in England shows evidence of language change. It is the text or script for a wedding ceremony. The text is mostly written in Latin, but some of the responses, the parts read by the people getting married, are written in early English. The passage is one that is still familiar today in many Christian wedding ceremonies. It reads:

With this ring I thee wed and this gold and silver I thee give: and with my body I thee worship: and with all my worldly catel [chattels] I thee honour.

Nan Kivell, Rex. (1819). Medieval manuscripts and documents from the Nan Kivell calligraphy collection,Series 3/Item 36/Verso 36 Religious Text, https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-229328970

This is an early form of English, but it is still understandable to most English-speaking people today. The spelling is unusual and inconsistent by modern standards, but until the late nineteenth century there were no rules about spelling. Words were written phonetically (how they sound). This plays an important part in learning about people of the past: from the way they spelled words, we can guess how their accent may have sounded.

The use of “Y” instead of “I” is common in early English written text. This can be seen in the original text: “Wyth thys rynge”. However, in the Latin text, there are no Ys. The letter Y was initially only added to the Latin alphabet to write words of Greek origin, but Latin does not contain any native words with the letter Y. Today we still have English words in them with “Y” as an “I”: for example, myth, system, byte.

This is an early form of English, but it is still understandable to most English-speaking people today. The spelling is unusual and inconsistent by modern standards, but until the late nineteenth century there were no rules about spelling. Words were written phonetically (how they sound). This plays an important part in learning about people of the past: from the way they spelled words, we can guess how their accent may have sounded.

The use of “Y” instead of “I” is common in early English written text. This can be seen in the original text: “Wyth thys rynge”. However, in the Latin text, there are no Ys. The letter Y was initially only added to the Latin alphabet to write words of Greek origin, but Latin does not contain any native words with the letter Y. Today we still have English words in them with “Y” as an “I”: for example, myth, system, byte.

Administration of the land

Laws help those in power to rule effectively. Laws set out expectations of every person (even the monarch) and set out what will happen if a law is broken. The legal system in Medieval times was complex, with laws, policies and decrees being written down and distributed to all parts of the kingdom. As most of the population could not read, a herald would read aloud the new law or decree in a public place.

A robust economy relied on trade and a complex web of industries. Keeping track of contracts, debts, indentures and business deals was important to the smooth functioning of the economy. As farming and production was the major employer of the ordinary people of Medieval society, economic or legal documents can give us more of a glimpse into the lives of ordinary people.

One of the great administrative documents of Medieval England was the Domesday Book (also written as the Doomsday Book). It was commissioned by William the Conqueror in 1086 CE as a survey of land and landowners in England and parts of Wales. As well as being a record of who owned what land, it was also used to calculate land taxes and other fees that could be owed to the Crown.

The National Library holds a copy of a page of the Domesday Book, printed in around 1861 CE. While not from the Medieval era, it is a fair approximation of the original. This page is a list of landholders and their properties in the county of Surrey (Sudrie), as written in red at the top of the page.

MS 4052-Medieval manuscripts and documents from the Nan Kivell calligraphy collection, circa 10th century-1819 [manuscript]./Series 1/Item 1/Recto 1. Legal Documents/Facsimile copy from the 'Domesday Book'. https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-204244712

Detail from: MS 4052-Medieval manuscripts and documents from the Nan Kivell calligraphy collection, circa 10th century-1819 [manuscript]./Series 1/Item 1/Recto 1. Legal Documents/Facsimile copy from the 'Domesday Book'. https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-204244712

Throughout the original document the initials T.R.E. can be seen. This is the abbreviation of the Latin Tempore Regis Edwardii – in the time of King Edward. This marking is used to compare land value and the land’s owners before the Norman Conquest of England, when many people lost their lands and property.

King Edward the Confessor died without an heir in January 1066. Many people claimed their right to the throne, including Harold Godwinson, Earl of Wessex, an English nobleman; Harald Hardrada, King of Norway; and William, Duke of Normandy, a French nobleman. Harold Godwinson was crowned King, but William and Harald contested Harold’s rule and invaded England, which led to the Battle of Stamford Bridge in September 1066, where Harald Hardrada was killed, and the Battle of Hastings in October 1066 where Harold Godwinson was killed. William of Normandy became King of England in December 1066. This was known as the Norman Conquest of England. William is usually known by the name William the Conqueror.

Throughout the original document the initials T.R.E. can be seen. This is the abbreviation of the Latin Tempore Regis Edwardii – in the time of King Edward. This marking is used to compare land value and the land’s owners before the Norman Conquest of England, when many people lost their lands and property.

King Edward the Confessor died without an heir in January 1066. Many people claimed their right to the throne, including Harold Godwinson, Earl of Wessex, an English nobleman; Harald Hardrada, King of Norway; and William, Duke of Normandy, a French nobleman. Harold Godwinson was crowned King, but William and Harald contested Harold’s rule and invaded England, which led to the Battle of Stamford Bridge in September 1066, where Harald Hardrada was killed, and the Battle of Hastings in October 1066 where Harold Godwinson was killed. William of Normandy became King of England in December 1066. This was known as the Norman Conquest of England. William is usually known by the name William the Conqueror.

The list in the upper left column comprises the main landholders in the county of Surrey, with King William (Rex Willelmus) at the top of the list. The list also includes the Archbishop of Canterbury, abbots, counts, countesses, earls and estates. The first paragraph outlines how much land the King owns in the county:

In Woking Hundred,

In Guildford, King William has 75 sites, whereon dwell 175 men.

Before 1066 they paid 18 0s 3d; now they are valued

at 30; however, they pay 32.

The rest of the document records how much land each person holds, how many people live there and how much tax they pay. From this document historians can map population density of an area (how many people lived in a certain area), what industries were present and even methods of production, as the property lists include how many ploughs and tools were present at each estate. In some cases, it indicated how the current owner came to own the property:

Ranulf the sheriff holds one site which he held hitherto from

the Bishop of Bayeux. But the men [of the County] testify

that it is not included in any manor, but that before 1066 its

holder granted it to Tovi, the town reeve, in payment of one

of his fines.

The Domesday Book measures land area in ways that are unfamiliar today:

Hundred – a subdivision of a shire or county. In Australia we have councils or shires. This is similar.

Hide – A ‘hundred’ was broken into several hides, each with different owners. A hide was the standard unit of measurement for tax purposes. One hide equals approximately 50 hectares in modern measurements.

Virgate – A smaller division of land. For every one hide there were four virgates.

It also documents the dues each estate must pay. It is clear to see that after 1066, the taxes and dues requested of some estates grew substantially:

In Wallington Hundred,

Archbishop Lanfranc holds Croydon in lordship. Before 1066 it

answered for 80 hides; now for 16 hides and 1 virgate.

Land for 20 ploughs. In lordship 4 ploughs;

48 villagers and 25 smallholders with 34 ploughs. A church.

A mill at 5s; meadow, 8 acres; woodland at 200 pigs.

Restold holds 7 hides of the land of this manor from the

Archbishop; Ralph, 1 hide. They have 7 8s in tribute from it.

Total value before 1066 and later 12; now 27 to the

Archbishop; to his men 10 10s.

Despite a system that preferenced men, it was possible for women to hold and manage property in their own names.

In Elmbridge,

Aldgyth of Elmbridge, a woman, holds 1 virgate from the King. Value 3s.

-------

The Bishop also has 1 further hide there. A widow holds it and

held it before 1066; she could go where she would. Then it

answered for 1 hide; now for nothing. Value 10s.

The University of Hull has an English transcription of the Domesday Book available on their website: https://hydra.hull.ac.uk/assets/hull:461/content

Indentured service

One of the major features of the Medieval European feudal system was the use of indentured service.

The word ‘indenture’ means a deed, contract or sealed agreement between two or more parties, in which one person is bound to serve another. Initially, indentures were used to describe a master-and-apprentice agreement. The term then evolved to include any system where one person was bound to work for someone else with little or no choice.

The word comes from the Middle English word “endenture” which is from the Old French word “endenteure”; from the jagged edges of these documents. These jagged edges were used to authenticate copies of the contract. Only the originals would fit perfectly together.

Watch Dr. Susannah Helman talk more about one of these documents [video].

The documents shown below are a set of indentures between Thomas Elliot the younger and his Father, Thomas Elliot thelder (the elder) and are dated 26 December 1587, during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I. Father and son would have received one of these each. At the bottom right of each document the names of each Thomas can be seen, the contract with the long seal tag attached is signed “by me Thomas Elliot”. The contract without the seal is signed “X Ellyott Senioris” (Elliot Senior).

They are written in English and many words are readable; however, the old style of handwriting makes it very difficult to decipher. The documents are made of parchment, a writing surface made from the specially prepared skins of sheep or goats.

The contract reads:

Thomas Elliot the yonger the sonne of Thomas Elliot thelder of the cittie of New Sarum, in the countie of Wiltes, 'tayler', to Thomas Elliott thelder, his father of the city and county aforesaid.

MS 4052-Medieval manuscripts and documents from the Nan Kivell calligraphy collection, circa 10th century-1819 [manuscript]./Series 1/Item 30/Recto 30. Legal documents/ Bond of apprenticeship, http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-208201467

Detail from: MS 4052-Medieval manuscripts and documents from the Nan Kivell calligraphy collection, circa 10th century-1819 [manuscript]./Series 1/Item 30/Recto 30. Legal documents/ Bond of apprenticeship, http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-208201467

MS 4052-Medieval manuscripts and documents from the Nan Kivell calligraphy collection, circa 10th century-1819 [manuscript]./Series 1/Item 30/Recto 29. Legal documents/ Bond of apprenticeship, https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-201696118

The places mentioned in the document still exist “the cittie of New Sarum, in the countie of Wiltes” is the modern city of Salisbury in the county of Wiltshire.

The places mentioned in the document still exist “the cittie of New Sarum, in the countie of Wiltes” is the modern city of Salisbury in the county of Wiltshire.

Thomas the younger entered a contract of indenture to his father to become a tailor. He would be his father’s apprentice for a period of seven years.

A modern transcription of the terms of the indenture are set out below:

Thomas Elliot the Younger promises:

- to serve his master well and faithfully,

- to keep his secrets,

- to do his lawful and honest commandments,

- to do no fornication in his master's house or elsewhere,

- to do no hurt to his master or suffer any to be done, but shall lett or warn his master thereof,

- not to haunt taverns,

- not to waste his master's goods, nor lend them to any man without his master's licence,

- not to contract matrimony within the said term,

- not to absent himself from the service of his said master by day or night, and to bear himself as a true and faithful servant in word and deed.

Thomas Elliot the Elder promises to teach and inform his apprentice in the art and mastery which he now uses after the best manner that he can, with reasonable chastisement and correction. Also he promises wholesome and sufficient meat and drink and lodging with linen, woollen hose and shoes and other necessary things for an apprentice after the custom of the city of New Sarum. At the end of the term, he shall give him double apparel and 3s 4d.

Transcript of an apprenticeship indenture.

This transcript is the whole contents of the document. It includes original spelling, punctuation, and grammar.

(// indicates the end of a line of script as it is written on the original document)

This Indenture made the xxvith Daie of December in the xxxth yere of the Raigne of our Soveraigne Ladie// Elizabeth by the grace of god Queene of England Fraunce and Ireland defender of the Faithe ec. witnesseth that// Thomas Elliot the yonger the Sonne of Thomas Elliot thelder of the Cittie of New Sarum in the Cowntie of Wiltes// Tayler hath put himselfe Apprentice to and wth the said Thomas Elliot thelder his father of the Cittie and Cowntie aforesaide// Tayler wth hime to dwell frome the daie of the date hereof unto thende of Terme of Seaven yeres from thence for the// next ensuige and fullie to be completed and endid for by and duringe all wch saide Terme the saide Thomas Elliot Apprentice// the said Thomas Elliot as his Maister well and faithefullie shall serve his secretes shall kepe, his comaundments lawfull//and honest… where shall doe no fornication in the howse of his saide Maister or elsewhere he shall comite hurte to his same// Maister hee shall none doe or suffer to be done but hee to his power shall it lett or his saide Maister thereof forthewiuthe warne and// gerve to understande. Taverns he shall not haunt, The goodes of his saide Maister inordinatlie he shall not wast nor them to anie// man lende wthout his Maister's license Matrymonye within the saide Terme he shall not contracte, nor himself to any// woman espouse frome the service of his said Maister by daie or night himself he shall not absent but as a trewe and// faithefull Servant orght to behave himselfe so shall he bear and behave hime selfe towards his said Maister ans well in/ Worde as Deed And the saide Thomas Elliot thelder the said Thomas Elliot theyounger his apprentise in the arte// and misterie wch he nowe usethe after the best manner that he can or maye shall teache and informe or cause to be//taught and informed as mutche as to the said arte and misterie belongeth or in any wise appertayneth with//reasonable chastisement and correction findinge his said Apprentice by all the tyme aforesaid houlsome and// sufficient meat and drink lodginge lynnen wollen hose and shoes and all other things meet and necessarye for an Apprentice// 155 of such a science to be found and alowed after the manner and custome of the said cittie of New Sarum. And further// to his saide Apprentice in thend of the same yeres doubbell apparell meet and convenyent for him to weare and three shillings// and fowerpence of Lawfull money shall geve and delyver. In witnes whereof the parties aforesaid to these indentures// interchangeablie have sette their hande and seales the daie and yere first above written. Signed Sealid and deliverid in// the presence of Thomas Murivall// Thomas Willis// Jo: Symons// By me Thomas Elliott.

Transcript of an apprenticeship indenture.

This transcript is the whole contents of the document. It includes original spelling, punctuation, and grammar.

(// indicates the end of a line of script as it is written on the original document)

This Indenture made the xxvith Daie of December in the xxxth yere of the Raigne of our Soveraigne Ladie// Elizabeth by the grace of god Queene of England Fraunce and Ireland defender of the Faithe ec. witnesseth that// Thomas Elliot the yonger the Sonne of Thomas Elliot thelder of the Cittie of New Sarum in the Cowntie of Wiltes// Tayler hath put himselfe Apprentice to and wth the said Thomas Elliot thelder his father of the Cittie and Cowntie aforesaide// Tayler wth hime to dwell frome the daie of the date hereof unto thende of Terme of Seaven yeres from thence for the// next ensuige and fullie to be completed and endid for by and duringe all wch saide Terme the saide Thomas Elliot Apprentice// the said Thomas Elliot as his Maister well and faithefullie shall serve his secretes shall kepe, his comaundments lawfull//and honest… where shall doe no fornication in the howse of his saide Maister or elsewhere he shall comite hurte to his same// Maister hee shall none doe or suffer to be done but hee to his power shall it lett or his saide Maister thereof forthewiuthe warne and// gerve to understande. Taverns he shall not haunt, The goodes of his saide Maister inordinatlie he shall not wast nor them to anie// man lende wthout his Maister's license Matrymonye within the saide Terme he shall not contracte, nor himself to any// woman espouse frome the service of his said Maister by daie or night himself he shall not absent but as a trewe and// faithefull Servant orght to behave himselfe so shall he bear and behave hime selfe towards his said Maister ans well in/ Worde as Deed And the saide Thomas Elliot thelder the said Thomas Elliot theyounger his apprentise in the arte// and misterie wch he nowe usethe after the best manner that he can or maye shall teache and informe or cause to be//taught and informed as mutche as to the said arte and misterie belongeth or in any wise appertayneth with//reasonable chastisement and correction findinge his said Apprentice by all the tyme aforesaid houlsome and// sufficient meat and drink lodginge lynnen wollen hose and shoes and all other things meet and necessarye for an Apprentice// 155 of such a science to be found and alowed after the manner and custome of the said cittie of New Sarum. And further// to his saide Apprentice in thend of the same yeres doubbell apparell meet and convenyent for him to weare and three shillings// and fowerpence of Lawfull money shall geve and delyver. In witnes whereof the parties aforesaid to these indentures// interchangeablie have sette their hande and seales the daie and yere first above written. Signed Sealid and deliverid in// the presence of Thomas Murivall// Thomas Willis// Jo: Symons// By me Thomas Elliott.

Contracts were also drawn up when landowners leased their land to others to work and manage. These contracts usually involved a tax or rent to be paid to the landlord.

This contract or lease by indenture from 20 May, 1553, is between Robert Howlesse, a draper (someone who sells fabric or clothing), and Henry Burge, a carrier (someone who transports goods or provisions). It sets out the rent owed and the period of the lease, 26 years.

The land lease begins on the feast day of the Nativity of St John the Baptist 1553 (24 June) until 1579.

The rent was to be paid four times a year on:

- Michaelmas – 29 September

- Christmas – 25 December

- Ladyday (The Feast of the Annunciation) – 25 March

- Midsummer (The Nativity of St John the Baptist) – 24 June

The land lease begins on the feast day of the Nativity of St John the Baptist 1553 (24 June) until 1579.

The rent was to be paid four times a year on:

- Michaelmas – 29 September

- Christmas – 25 December

- Ladyday (The Feast of the Annunciation) – 25 March

- Midsummer (The Nativity of St John the Baptist) – 24 June

The contract states:

All that his messuage or tenement with all Stables, Sellers, Sollers, Chambers, Romes, Edyfices & buyldynges to the same messuage or tenement belonging with all & Synglar thappurtenances set lying and beying yn the Citye of New Sarum afforesaid yn the countye afforesaid yn the north syde of a Strete there called Chypperland Strete between a tenement of the said Robert Howlesse on the East partye & garden in the tenure of John Plather on the west partye & tenement of John Eyer and the said Strete on the South parte.

Term:

From the feast of the Nativity of St. John the Baptist next after the date hereof for the term of twenty-six years.

Rent:

Yielding sixteen shillings at the four usual feasts, namely Michaelmas, Christmas, Ladyday and Midsummer in four equal parts.

Activities

- Sounding out a word can help spellers understand a word by the sounds we use to build the word; however, this doesn’t always lead to the correct dictionary spelling. “Phone” may be written “fown” if written purely on sound.

- Ask students if they have ever been asked to “sound it out” while trying to spell a word.

- Write a short passage of text containing commonly used words known to the students, including a few examples of very complex words likely unknown to the students.

- Read the passage slowly and have the students write down your words as they listen. Ask them to spell what they hear. If they don’t know the correct spelling, sound it out.

- Have the students cover their writing.

- Read the passage twice more affecting a different manner of speaking each time, stressing different syllables and sounds and pronouncing words slightly differently.

- Have the students compare each of their writings. Did their understanding of the spelling change with the different way of speaking?

- Have them compare with a friend to see variations of spellings. This can demonstrate the reasons behind historical documents having inconsistent spelling.

- Have the students read the contract of Thomas Elliot the younger (or part of) in its original form. You may need to format it and check for appropriateness of the text.

- Can they understand the text by sounding out the words as they are spelled?

- Can they recognise words even though they are written differently to today’s spelling?

- Conduct a class survey to find out what kinds of documentary evidence we produce in our modern lives.

- Ask students to consider the ways we communicate these days and what people might be able to learn about us from these communications.

- The Australian legal system defines documentary evidence that can be given as evidence against someone. Read the definition here. There is also a definition of electronic communications that can be presented.

- Have students evaluate their electronic footprints and consider how much they share in the online space.