Due to scheduled maintenance, the National Library’s online services will be unavailable between 8pm on Saturday 7 December and 11am on Sunday 8 December (AEDT). Find out more.

Today, we can find the meaning of a word online. In the past, we only had physical dictionaries. (I had a 1980 reprint of The Australian Pocket Oxford Dictionary (1976), covered in royal blue contact paper.)

Just as we change throughout our lives, the words we use are everchanging. Dictionaries have been published to be useful references, but they are quickly superseded as time passes.

The National Library of Australia holds over 26,000 dictionaries in hard copy, with many more available digitally. Over 1000 of our hard copy dictionaries date prior to 1850, in around 25 languages. They include landmarks in the history of the book and important records of languages and subjects.

The Library holds the rare books collection, as well as the papers, of one of history’s great dictionary makers (or lexicographers) C.T. Onions (1873–1965) best known for the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary (1933) and the Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology (1966). We also hold manuscripts and rare books of the British bibliographer Robin Alston (1933–2011). Many of Alston’s rare books are dictionaries, some the sole surviving copies.

This blog explores some of these treasures. It shows that dictionaries can not only be important historical records, but also varied, intriguing, even beautiful, as well as useful.

The first dictionary of the English language is said to be Robert Cawdrey’s A Table Alphabetical (1604). Only one first edition survives at the Bodleian Library, Oxford. (We have a recent edition of 2007.)

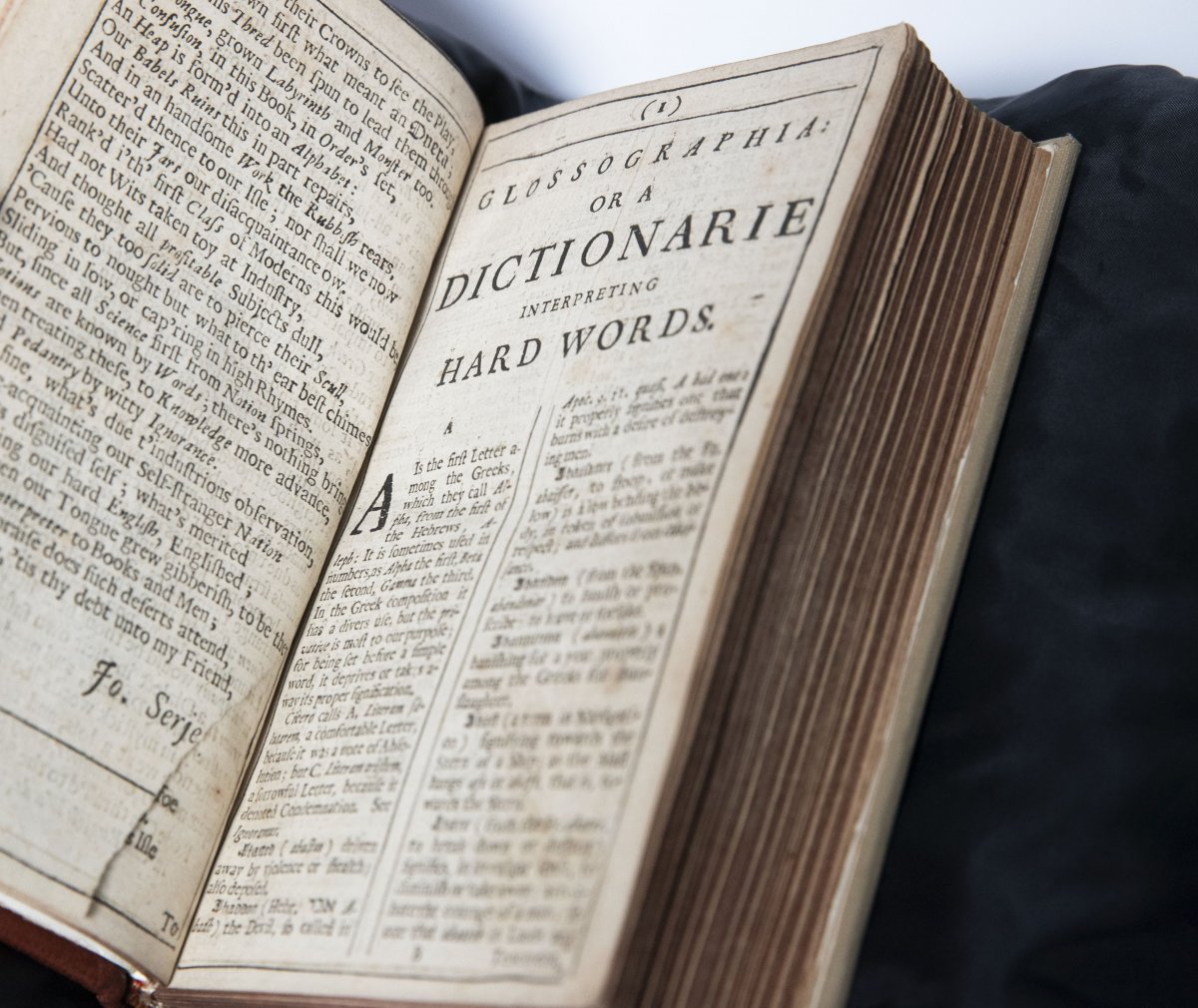

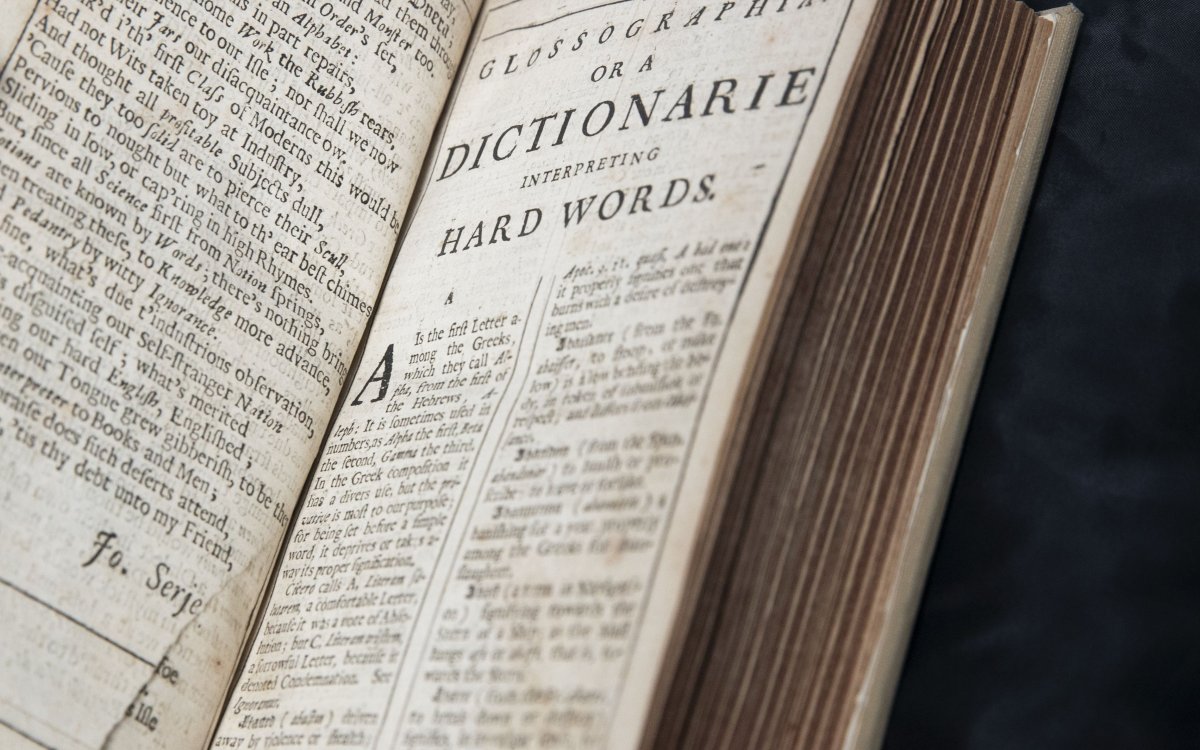

One of our earliest major English dictionaries is Thomas Blount’s Glossographia (1656), which we have in first and fifth editions.

The title page says it will be ‘Very usefull for all such as desire to understand what they read’—a worthy aim for any dictionary.

It makes much of its being a dictionary of ‘hard words’. The letter to the reader explains at length:

After I had bestowed the waste hours of some years in Reading our best English Histories and Authors; I found, though I had gained a reasonable knowledge in the Latine and French Tongues, as I thought, and had a smattering both of Greek and other Languages, yet I was often gravell’d in English Books; that is, I encounter’d such words, as I either not at all, or not thoroughly understood, more than what the preceding sense did insinuate

He then lists some of these ‘hard words’, numerous specialist and European words. For example:

In the Spanish, the Escurial, Infanta, Sanvenito, &c. ... The Shoo-maker will make you Shoos with Galloches; or with Flaps and Ferry-boats; Boots Whole-chase, Demichase, or Bottines, &c. The Barber will modifie your Beard A la Franchesa, a la Gascoinade &c.

He names his audience:

It is chiefly intended for the more-knowing Women, and less-learned Men; or indeed for all such of the illiterate, who can but find, in an Alphabet, the Word they understand not; yet I think I may modestly say, the best of Scholars may, in some part or other, be obliged by it.

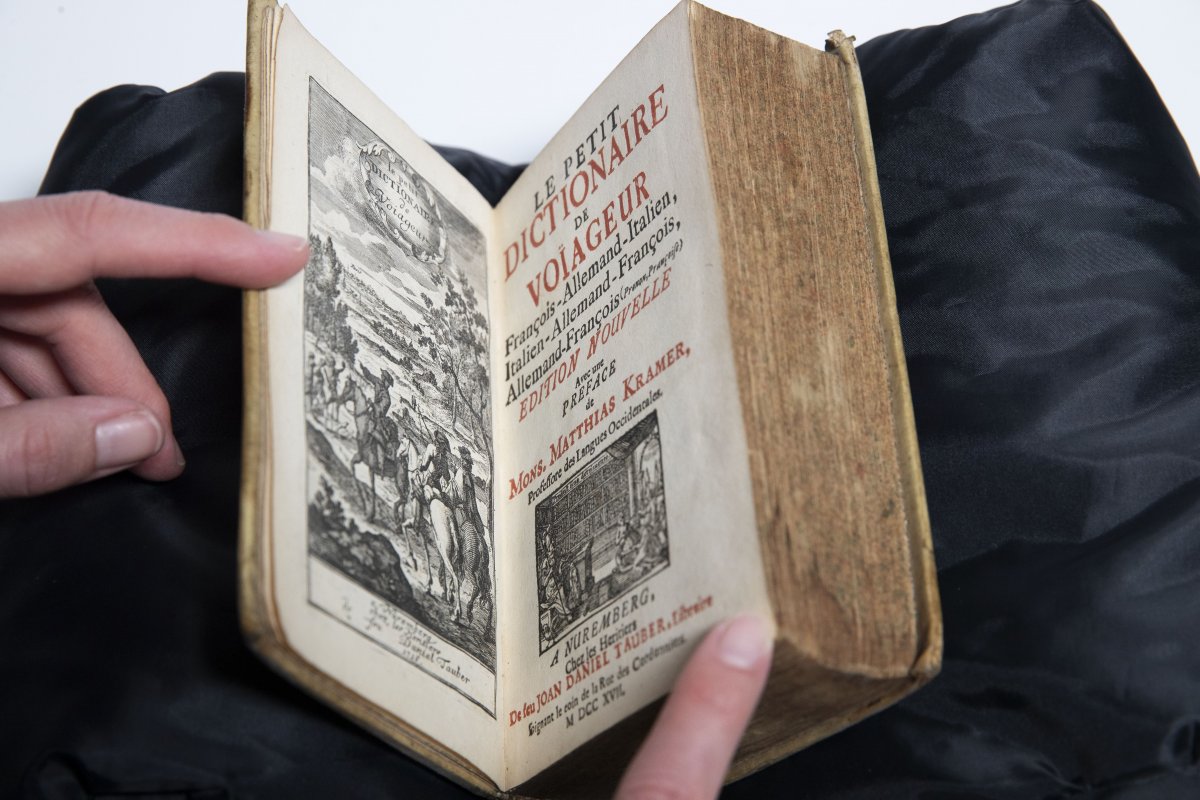

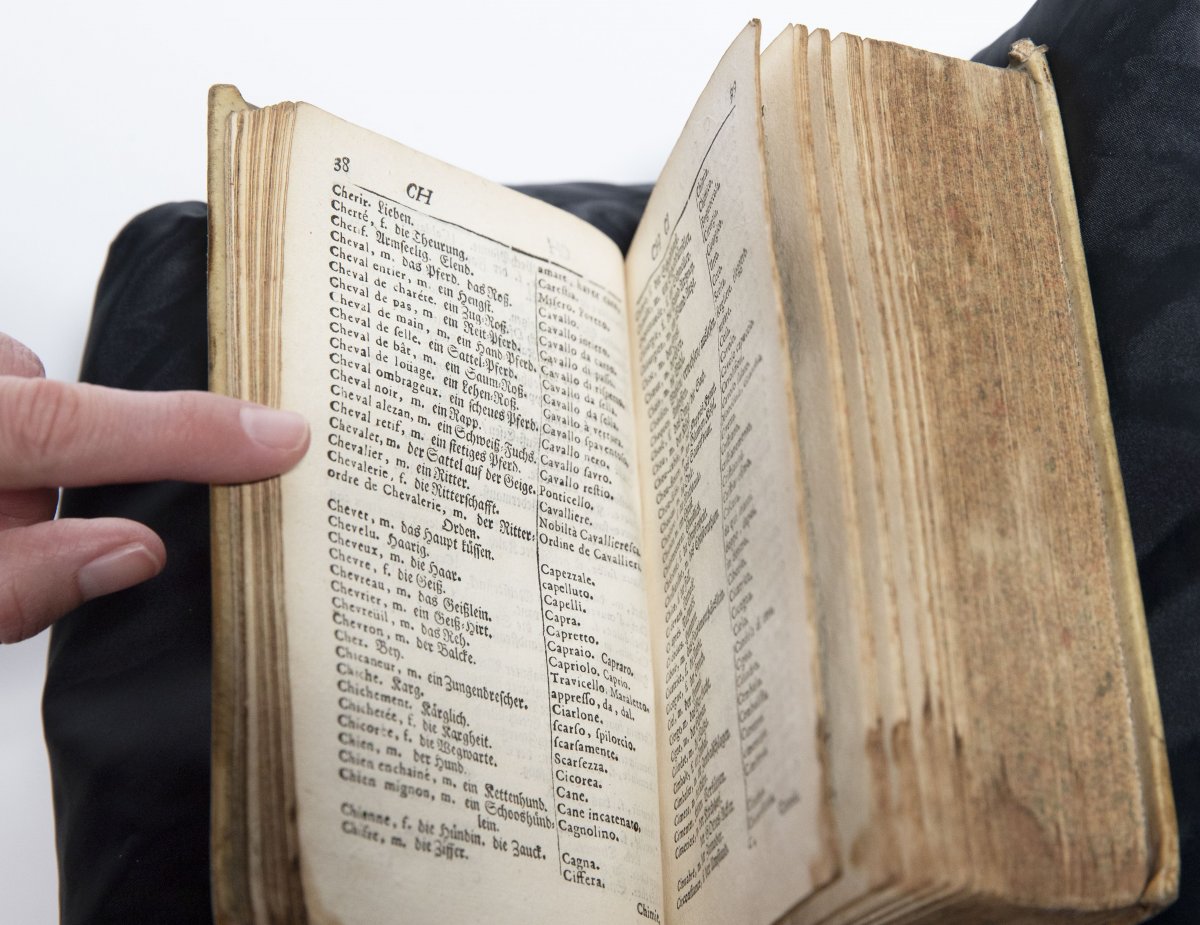

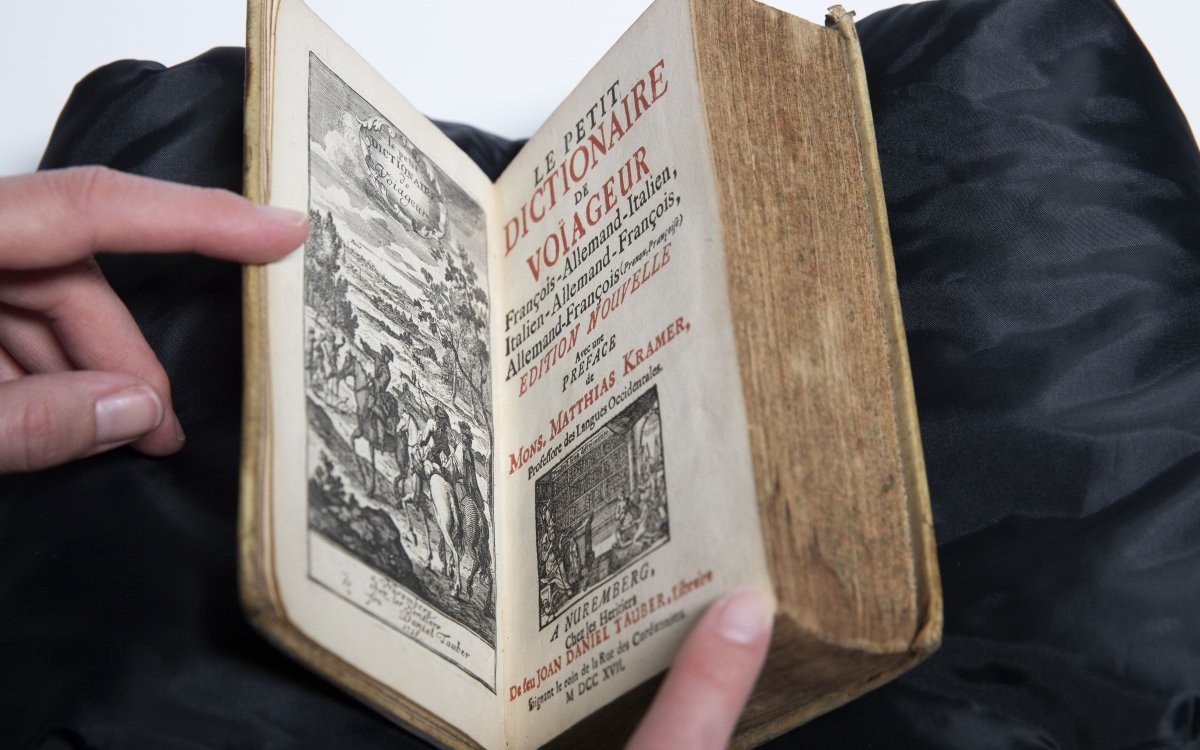

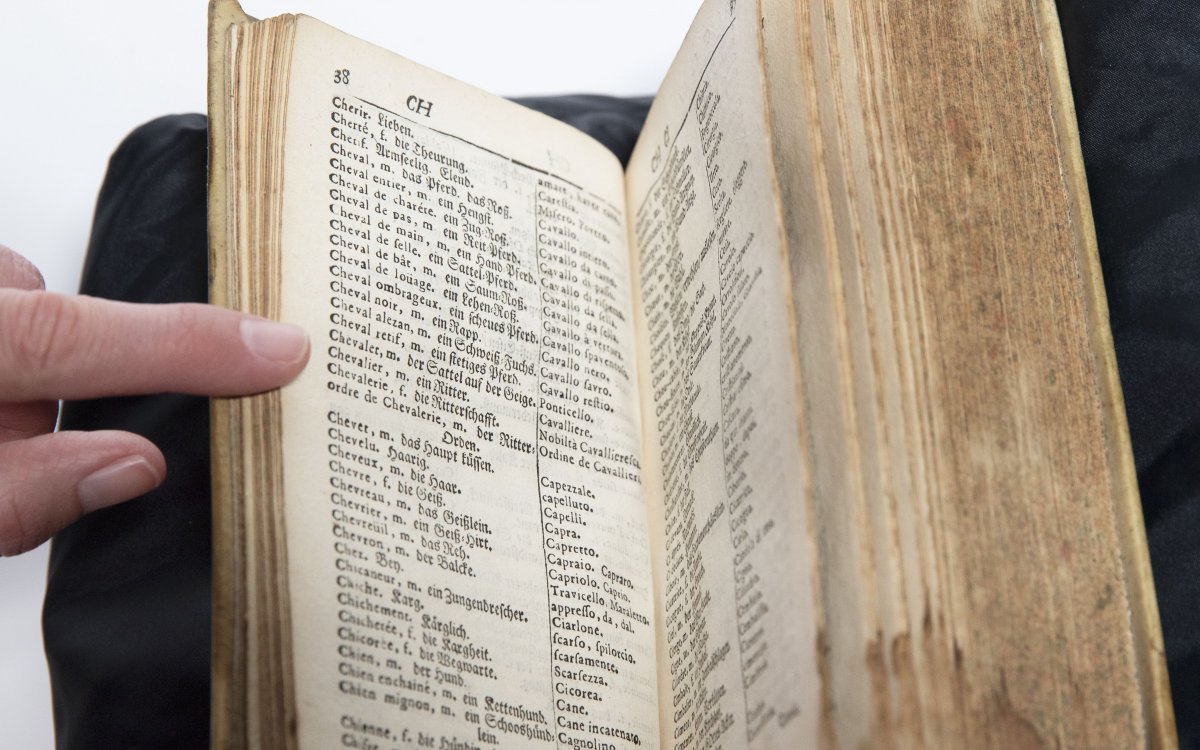

We have dictionaries for travellers:

Kramer was a Nuremberg lexicographer, and author of several dictionaries. This one has several sections—the first French-German-Italian, the second Italian-German-French, and the last German-French. Few copies survive in libraries worldwide.

This copy is in a vellum binding, which someone has taken the time to give a title in ink on the spine.

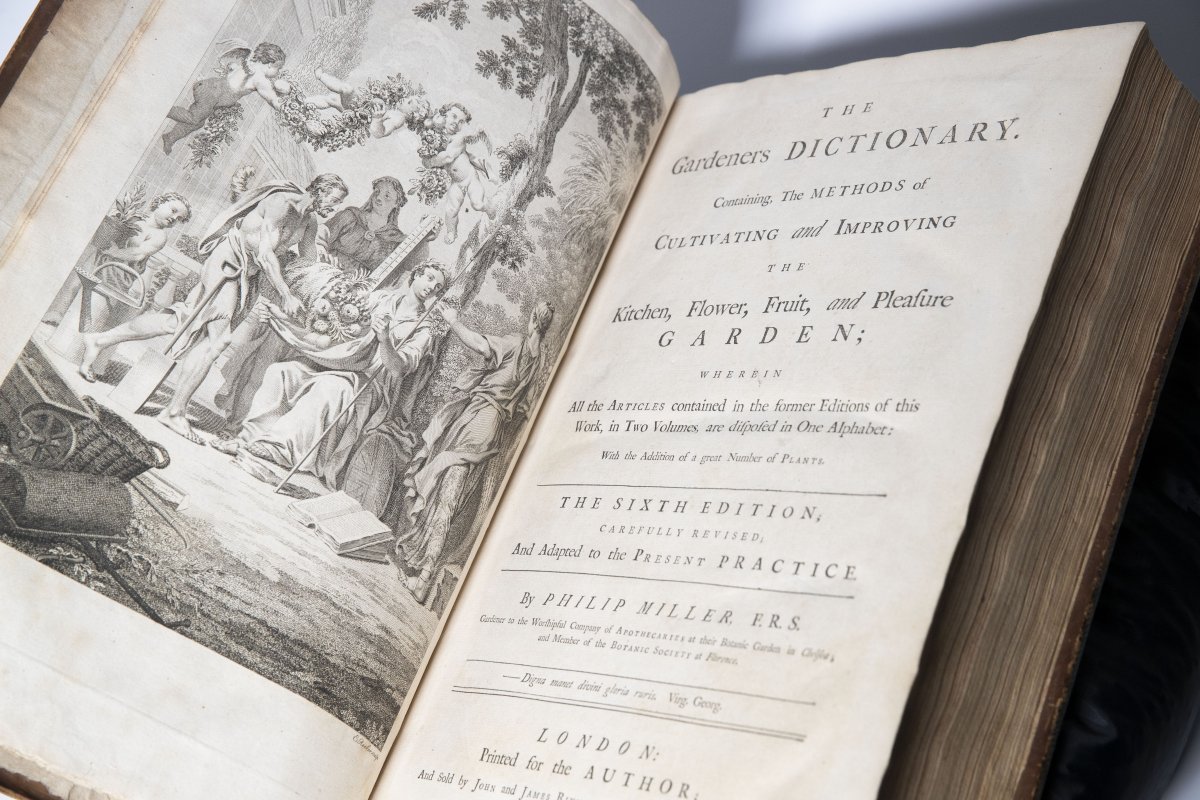

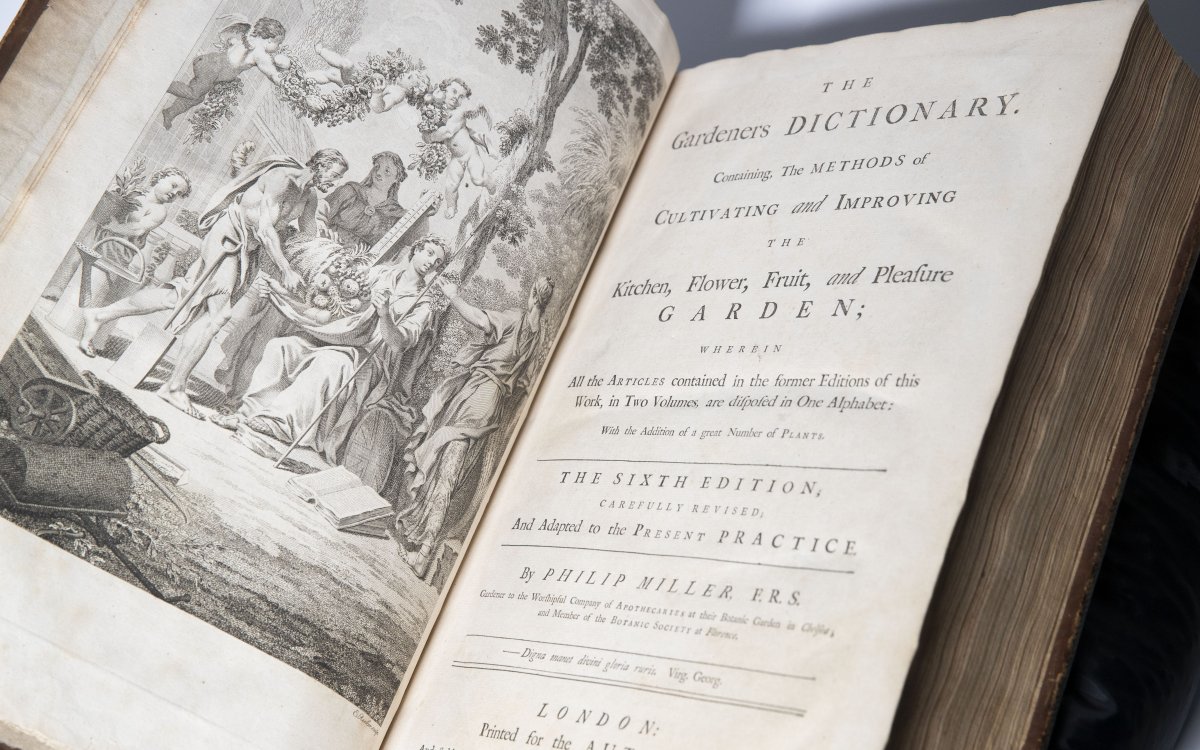

Dictionaries for gardeners

For nearly fifty years, Miller was gardener to the Worshipful Company of Apothecaries at their Botanic Garden in Chelsea. This dictionary was his most important work, and ran to eight editions over several decades. This is the sixth edition and is folio size – meaning it is large and heavy. The Library also holds the first edition of 1731.

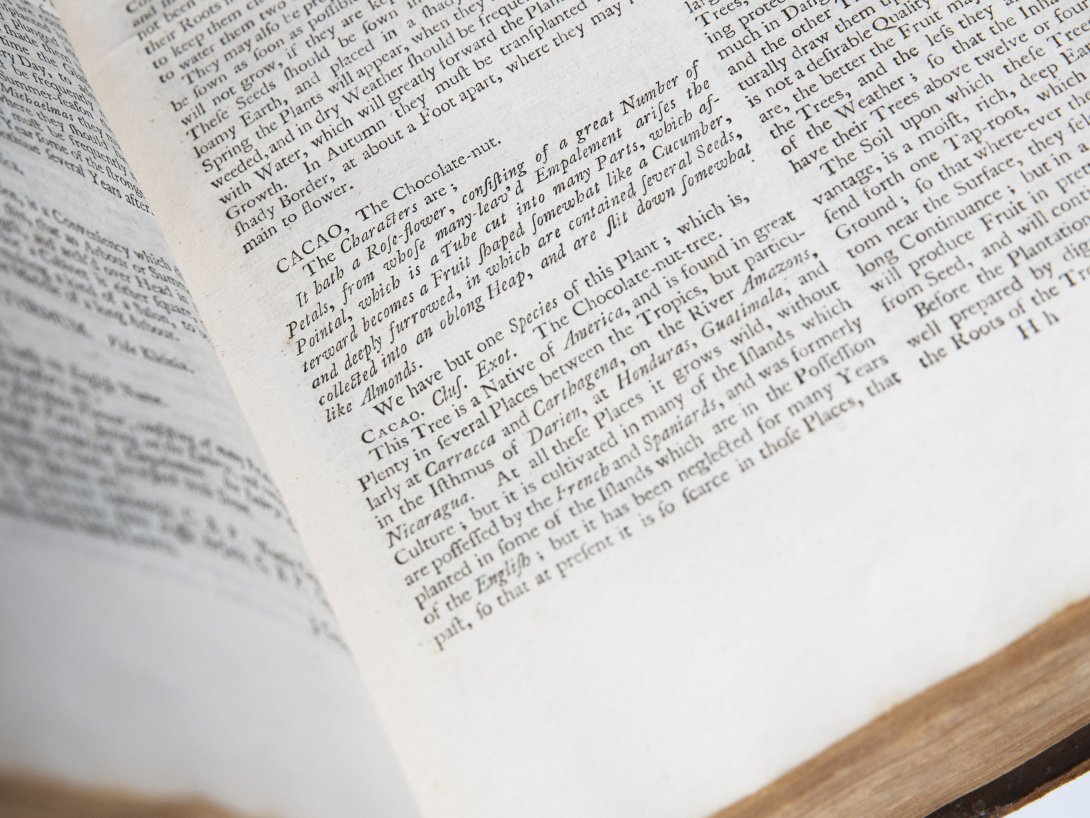

As it’s close to Easter, it feels appropriate to highlight the entry for

CACAO, The Chocolate-nut.

The Characters are;

It hath a Rose-flower, consisting of a great Number of Petals, from whose many-leav-d Empalement arises the Pointal, which is a Tube cut into many Parts, which afterward becomes a Fruit shaped somewhat like a Cucumber, and deeply furrowed, in which are contained several Seeds, collected into an oblong Heap, and are slit down somewhat like Almonds.

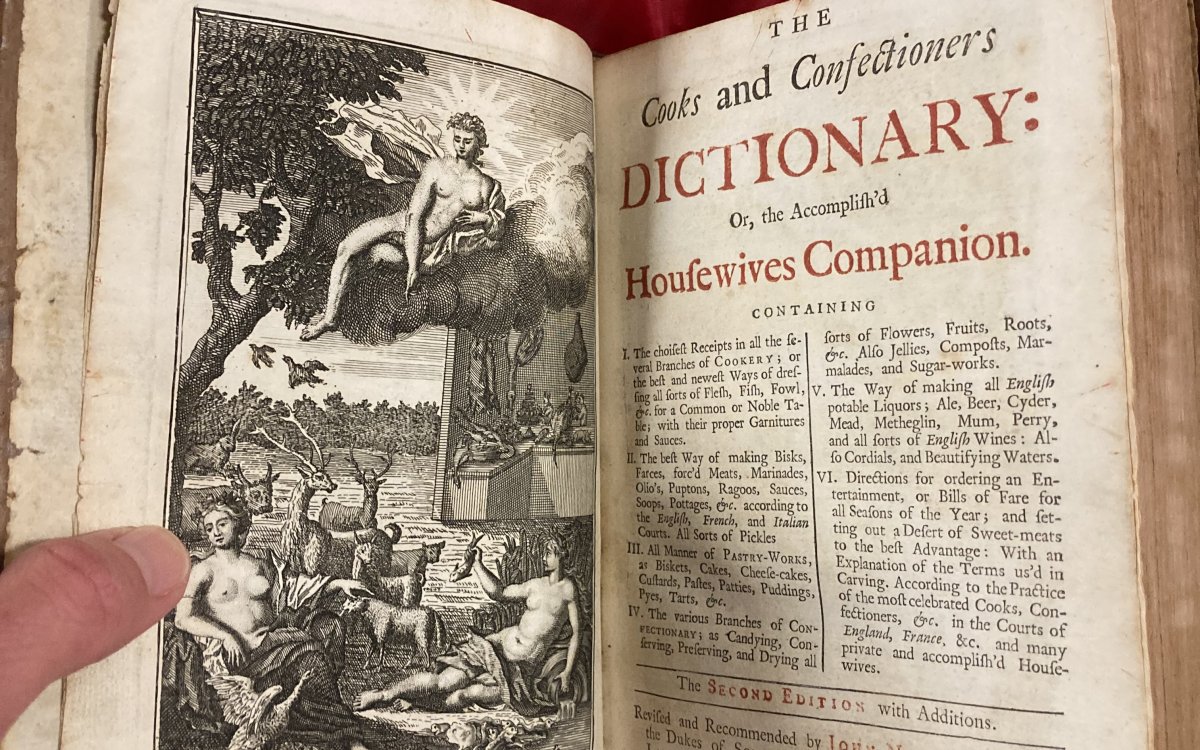

Dictionaries for sweet tooths

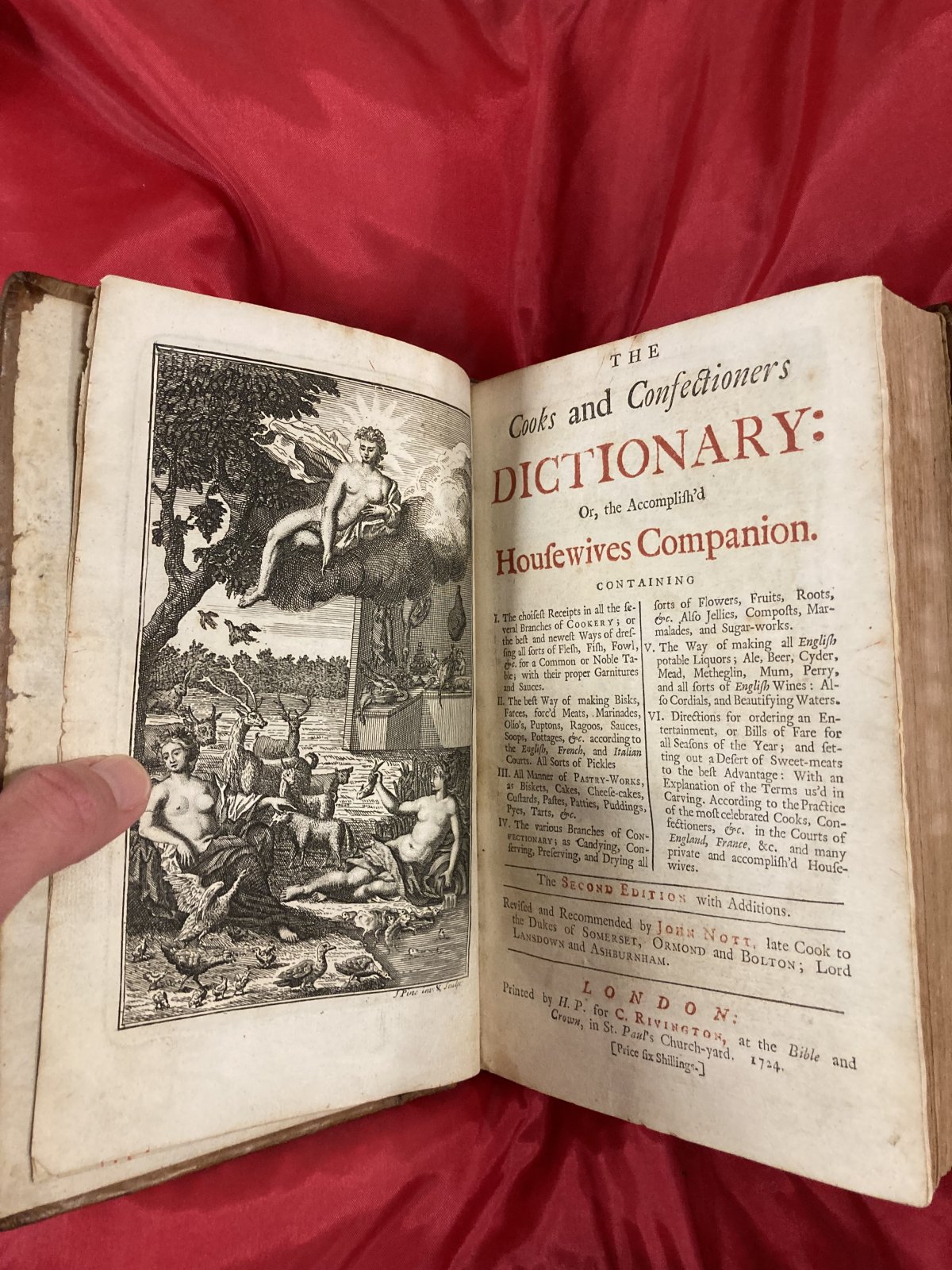

The author John Nott was cook to numerous British aristocrats. This is the second edition, the first having appeared in 1723.

Though organised like a dictionary, it is more of a companion or collection of recipes. Continuing the theme, here are a few entries for chocolate:

128. To make Chocolate Biskets

SCRAPE a little Chocolate upon the Whites of Eggs, so much as will give it the Taste and Colour of the Chocolate. Then mingle with it powder’d Sugar, ‘till it becomes a pliable Paste. Then dress your Biskets upon Sheets of Paper, in what Form you please, and set them into the Oven to be bak’d with a gentle Fire, both at top and underneath.

…

131. Chocolate Cream.

BOIL a quarter of a Pound of Sugar in a Quart of Milk, for a quarter of an Hour; beat up the Yolk of an Egg, put it into the Cream, and give it three or four boils. Take it off the Fire, and put in Chocolate, till you have given the colour of Cream: Then boil it for a Minute, strain it through a Sieve, and serve it in CHINA Dishes.

CINNAMON Cream is made after the same manner.

132. To make a Chocolate Tart.

Mix a little Milk, the Yolks of ten Eggs, with two Spoonfuls of Rice-flour, and a little Salt; then add a Quart of Cream, and sugar to your Palate; make it boil, but take care it do not curdle; then grate Chocolate into a Plate; dry it at the Fire; and having taken off your Cream, mix your Chocolate with it, stirring it well in, and set it by to cool. Then sheet a Tart-pan, put in your Mixture, bake it. When it comes out of the Oven, glaze it with powder’d Sugar and a red hot Shovel.

Who knew dictionary entries could sound so delicious! Where is my ‘red hot Shovel’?

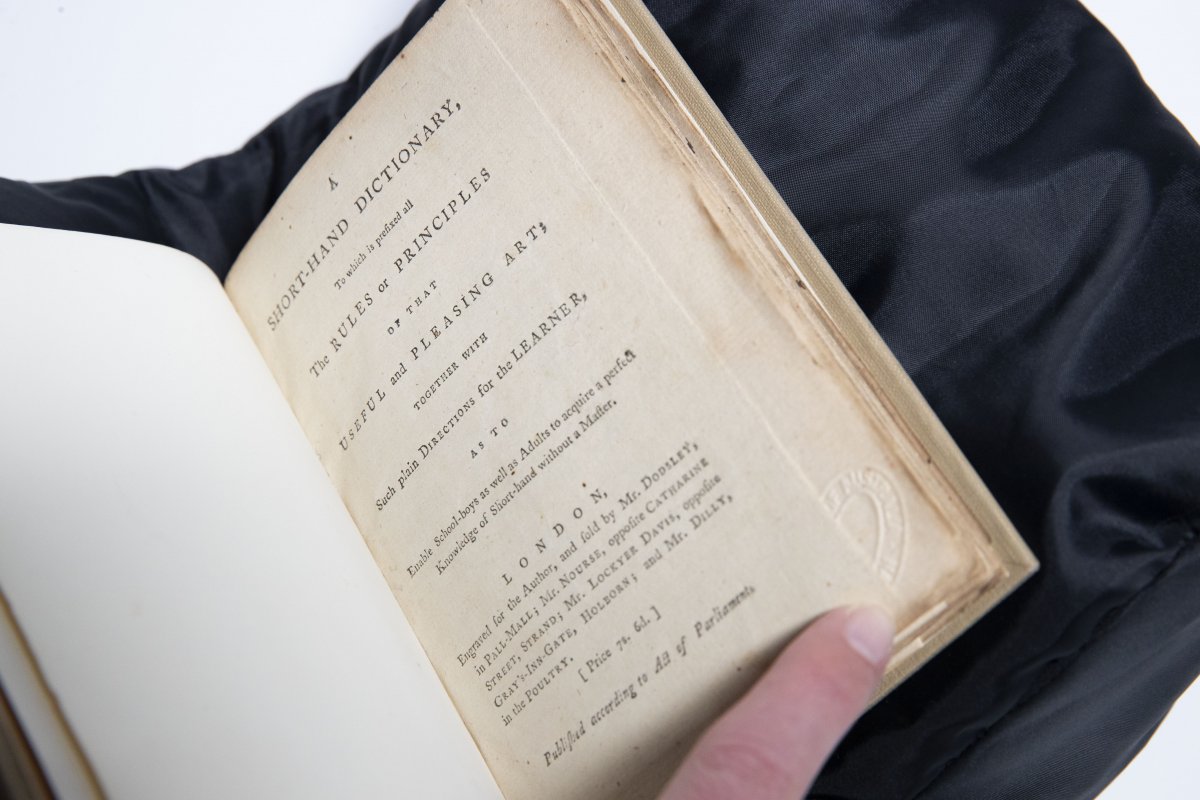

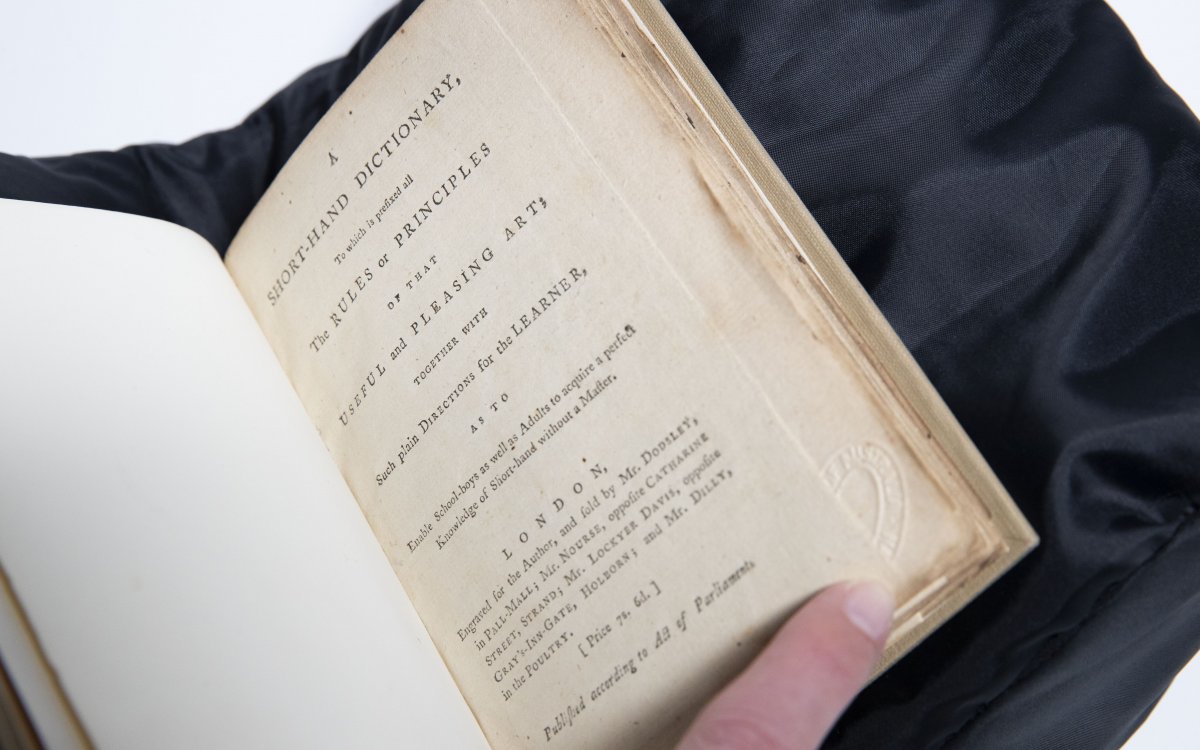

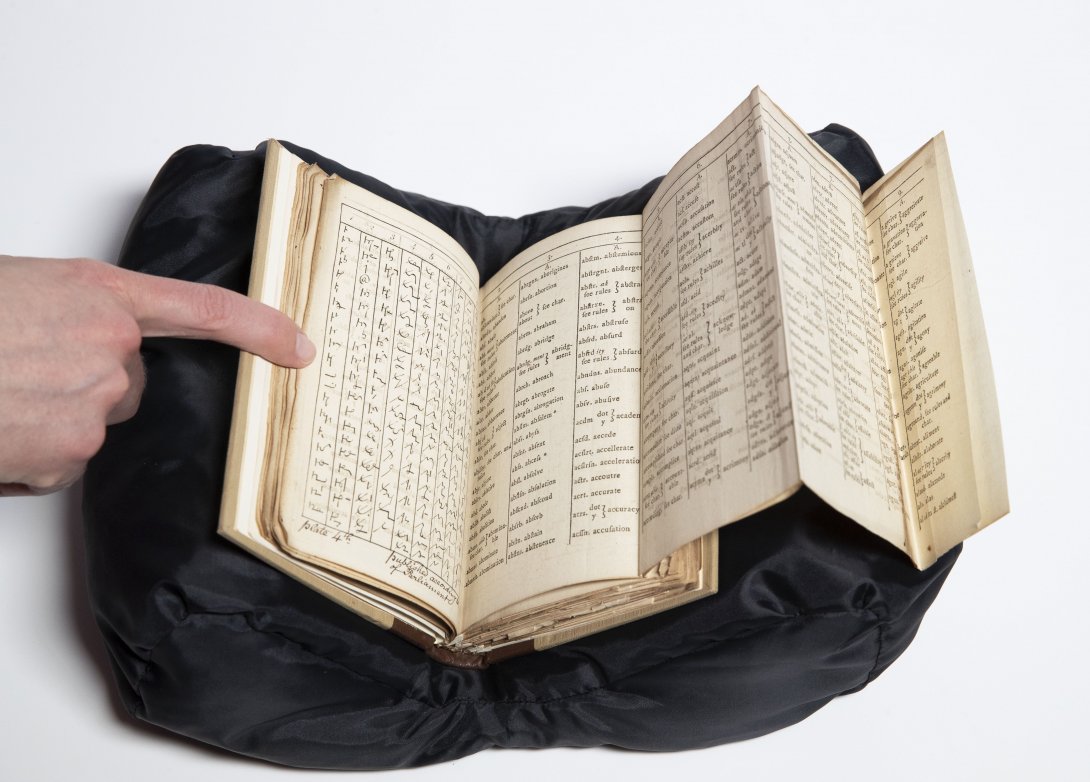

Dictionaries for writers of shorthand

This dictionary aims to make learning shorthand easy. The author says in the introduction:

Short-hand, nevertheless, like a juggler’s trick, is only mysterious to those who are unacquainted with it’s [sic] principles; and indeed the very learning of such gentlemen as have hitherto obliged the public with books of instruction, have been the great means of increasing those difficulties to the learner, they were intended to remove; for scientific terms are alone familiar to the scholar.

The plates are engraved, and individually annotated.

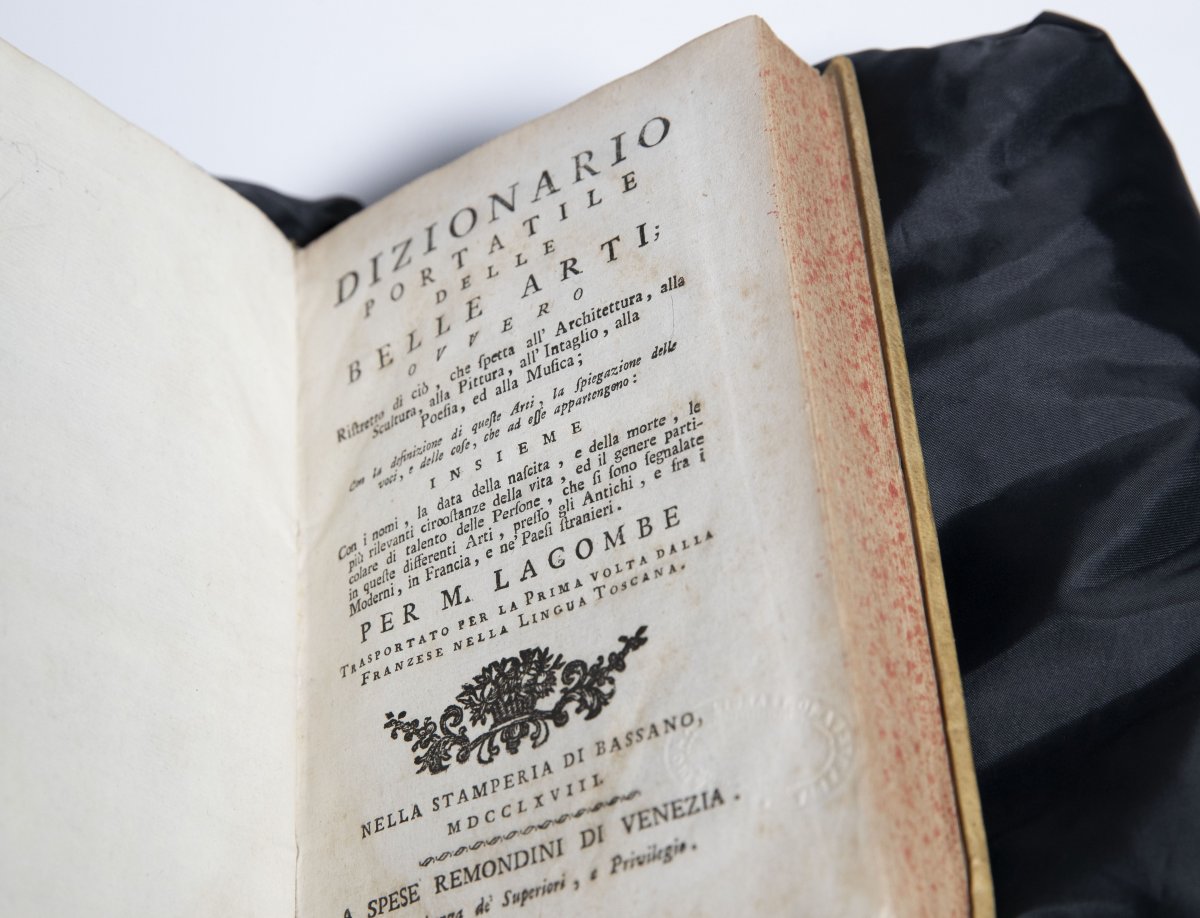

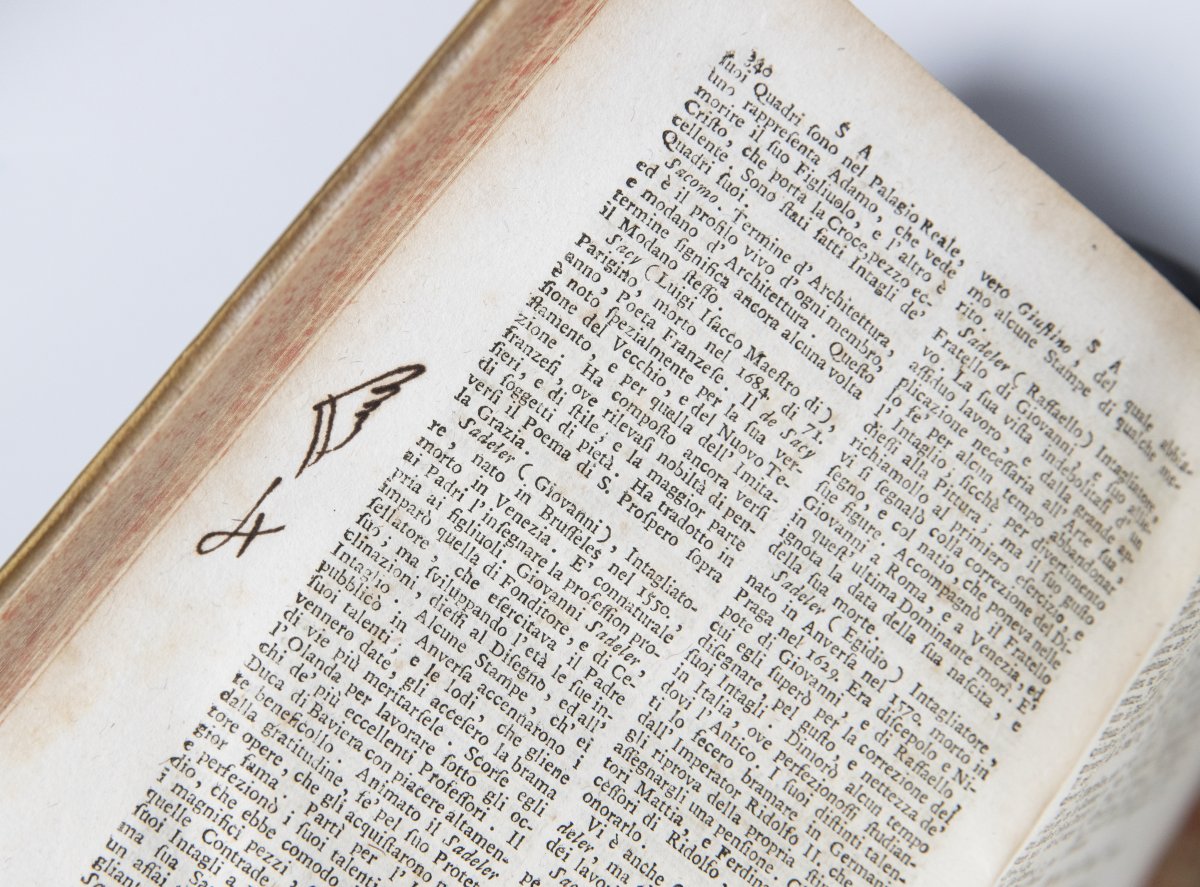

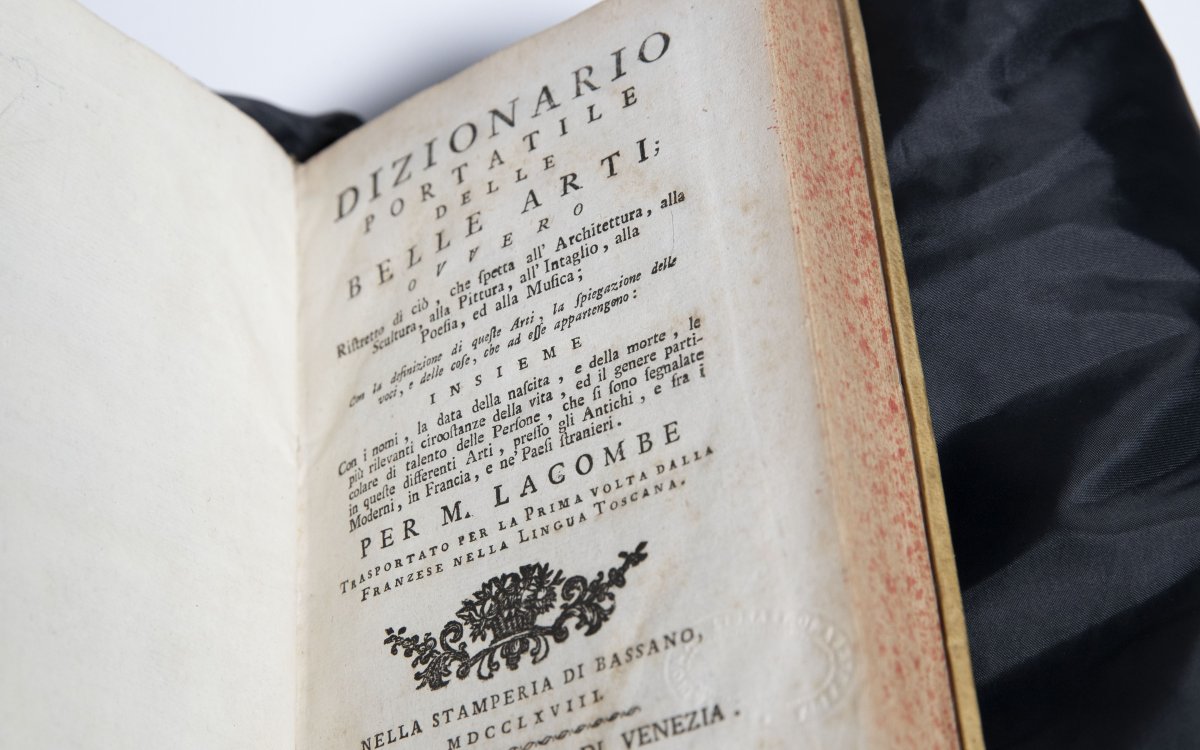

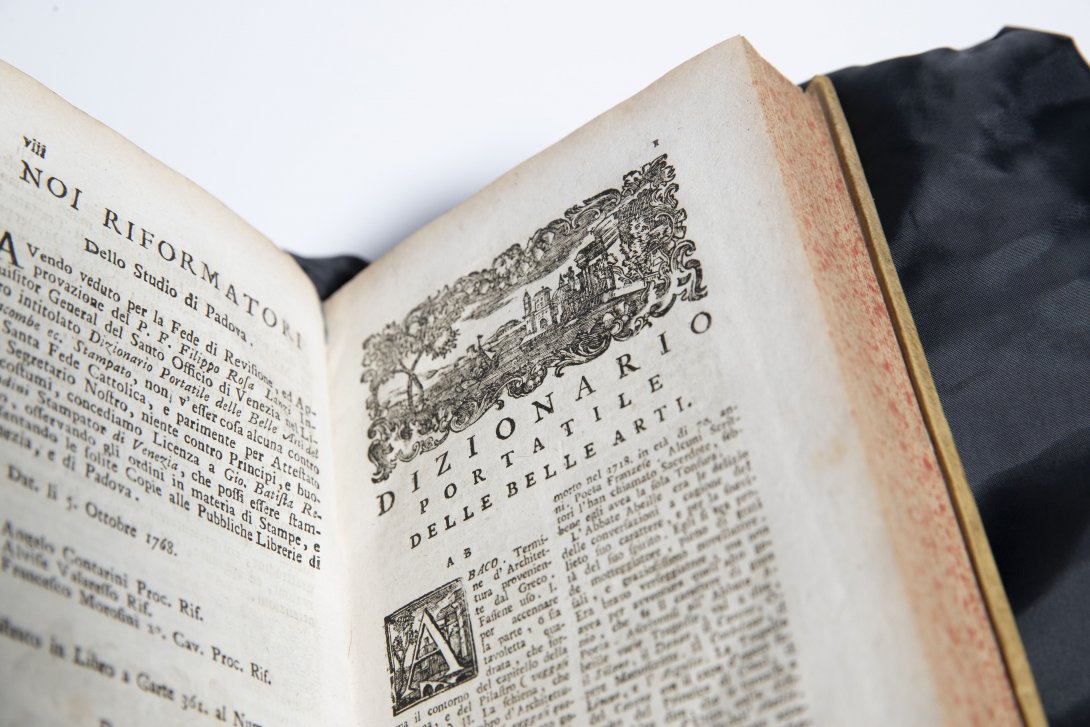

Dictionaries for lovers of the fine arts

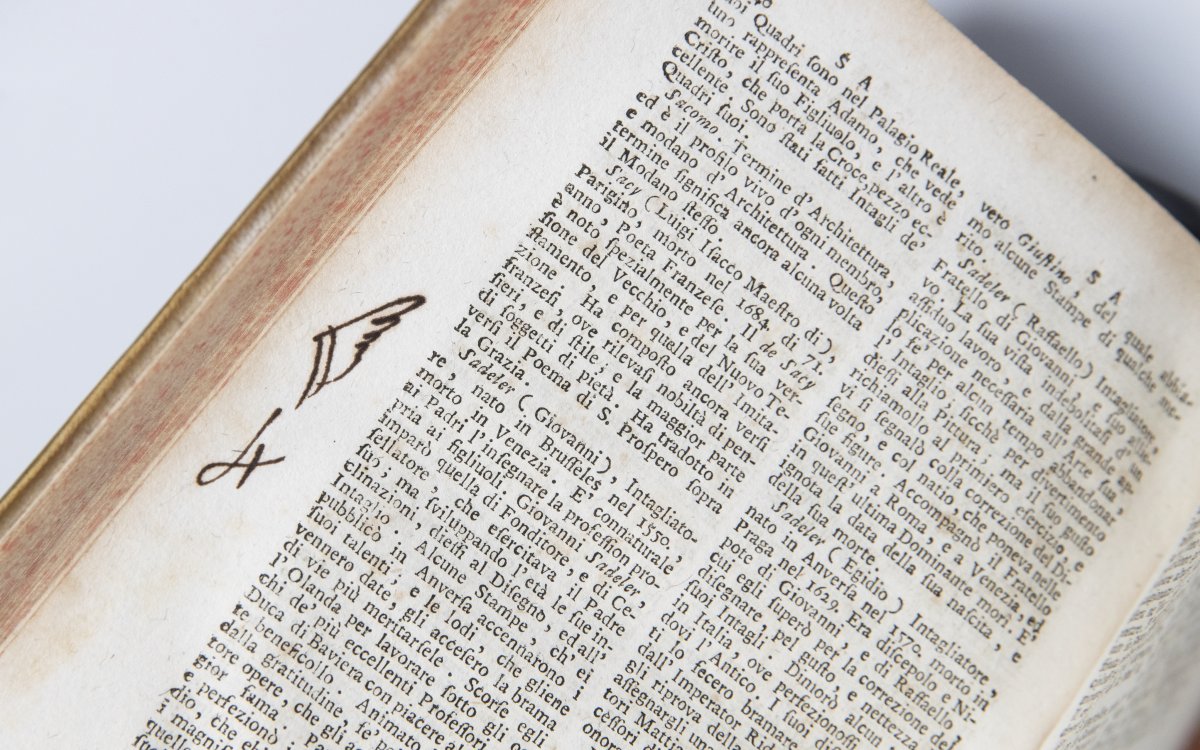

It shows that dictionaries can be beautiful. This book features vignettes and initials to inspire the reader.

This is an Italian translation – in the Tuscan dialect – of the original French edition of 1752. The dictionary covers architecture, sculpture, painting, engraving, poetry and music and important French and overseas practitioners of the same from ancient and modern times. Lacombe was a French lawyer, who also published numerous dictionaries on specialist topics such as gardening, fish, mathematical games and the analysis of historical documents (diplomatics). This book belonged to the British lexicographer C.T. Onions, and he has inscribed his name on the front endpaper. An earlier reader of this book has drawn many little hands in the margins in iron gall ink, pointing to entries he or she must have thought important.

Famous dictionaries

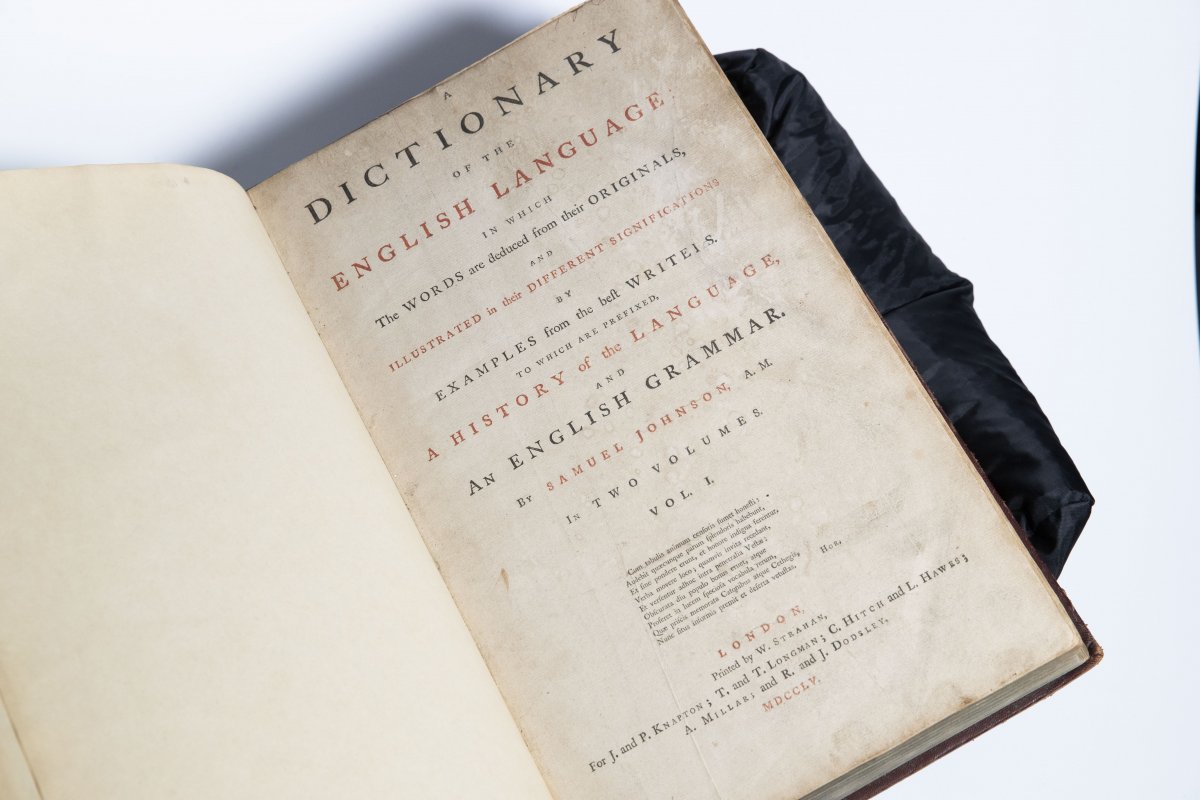

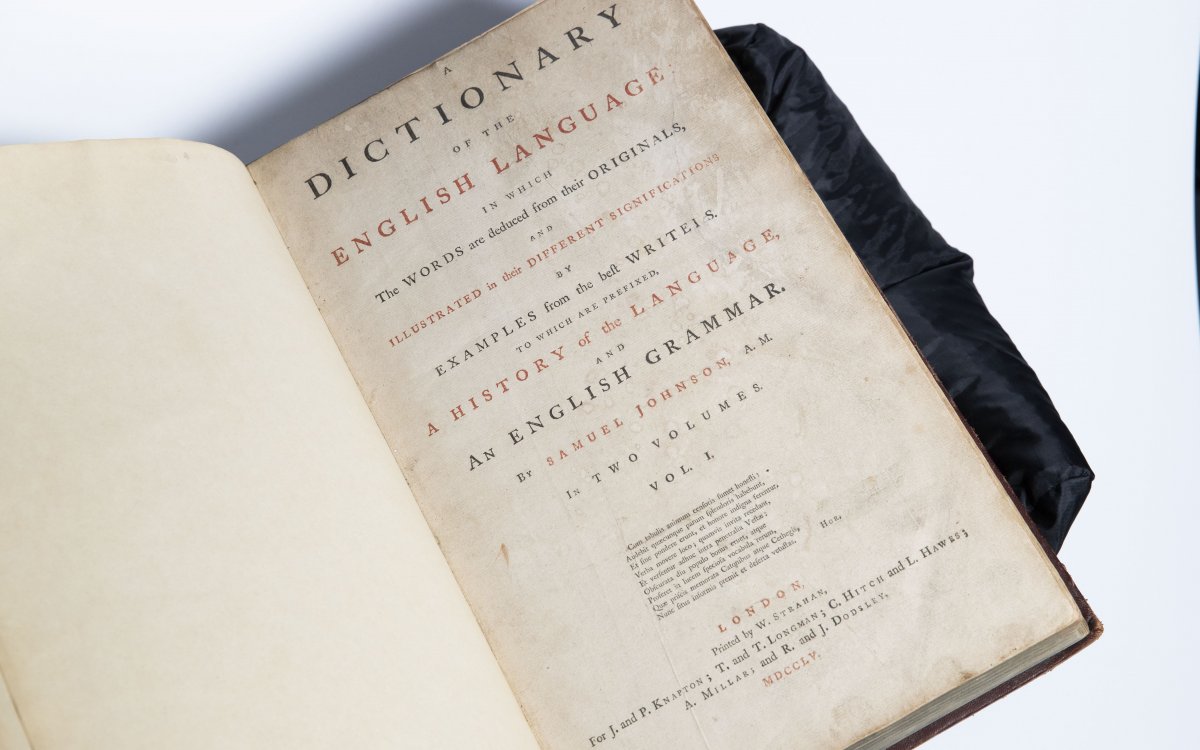

In two volumes, Dr Samuel Johnson, the distinguished essayist, playwright, critic and poet, created this, the first great English dictionary. From the garret of his London home and with the assistance of a group of often down-and-out assistants, he ‘turn[ed] over half a library to make one book’. The definitions, etymologies and countless quotations are pervaded by Johnson’s erudition, humour, tastes and views. If you’re ever in London, you can visit his Gough Square house, and the very room in which the dictionary was compiled.

The Library holds two first editions of Dr Johnson’s dictionary. Author Henry Hitchings has called it ‘the most important British cultural monument of the eighteenth century’. The dictionary was the most widely used dictionary of English, including in Australia, until the publication of the Oxford English Dictionary from 1895.

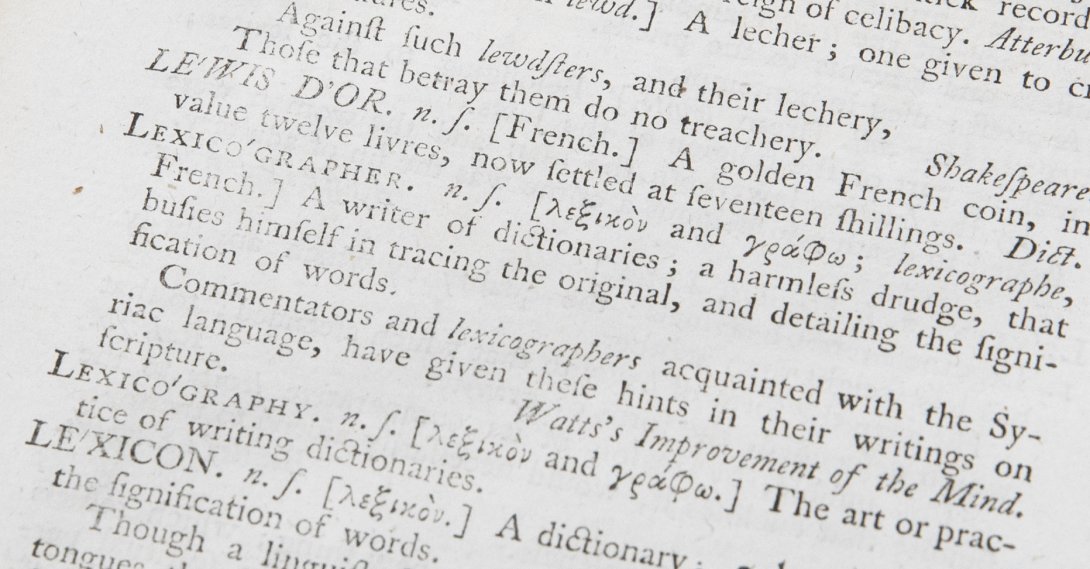

Johnson could laugh at himself. For example, his definition of ‘lexicographer’:

A writer of dictionaries; a harmless drudge, that busies himself in tracing the original, and detailing the signification of words.

The Library also holds a good collection of Dr Johnson’s publications, many of them first editions.

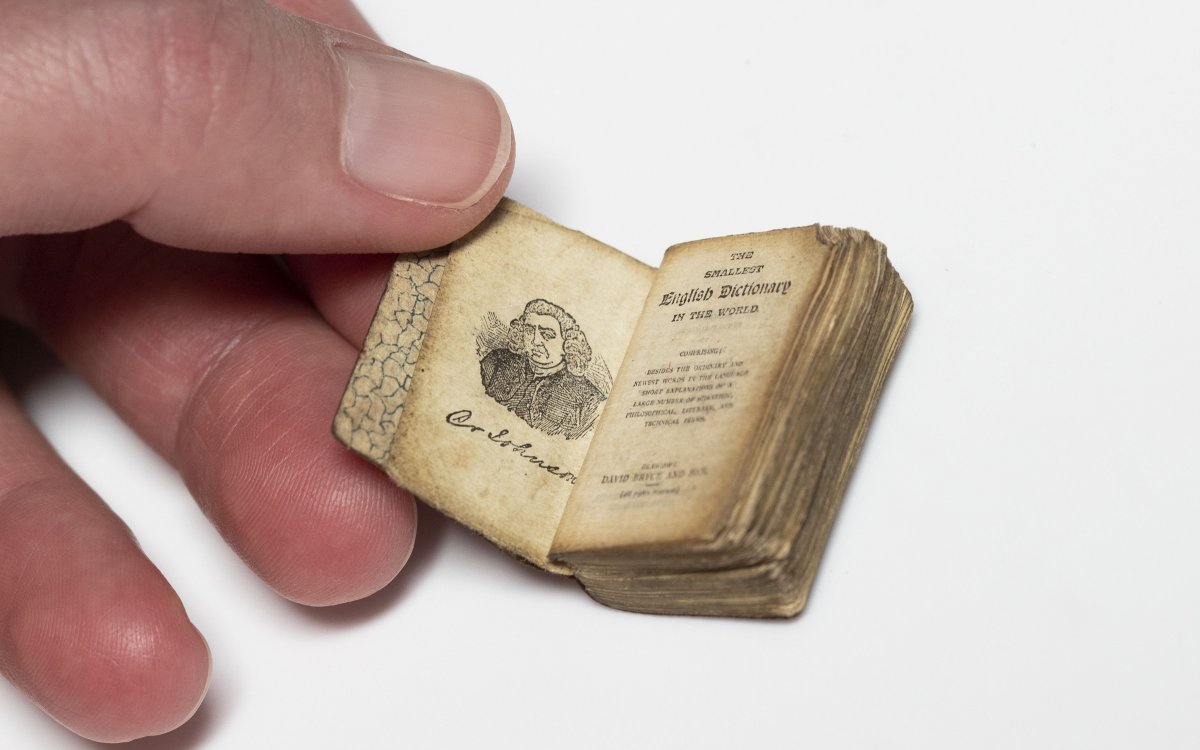

We also have the dictionary in miniature:

Our holdings of Australian dictionaries are extensive and we can’t do them justice here.

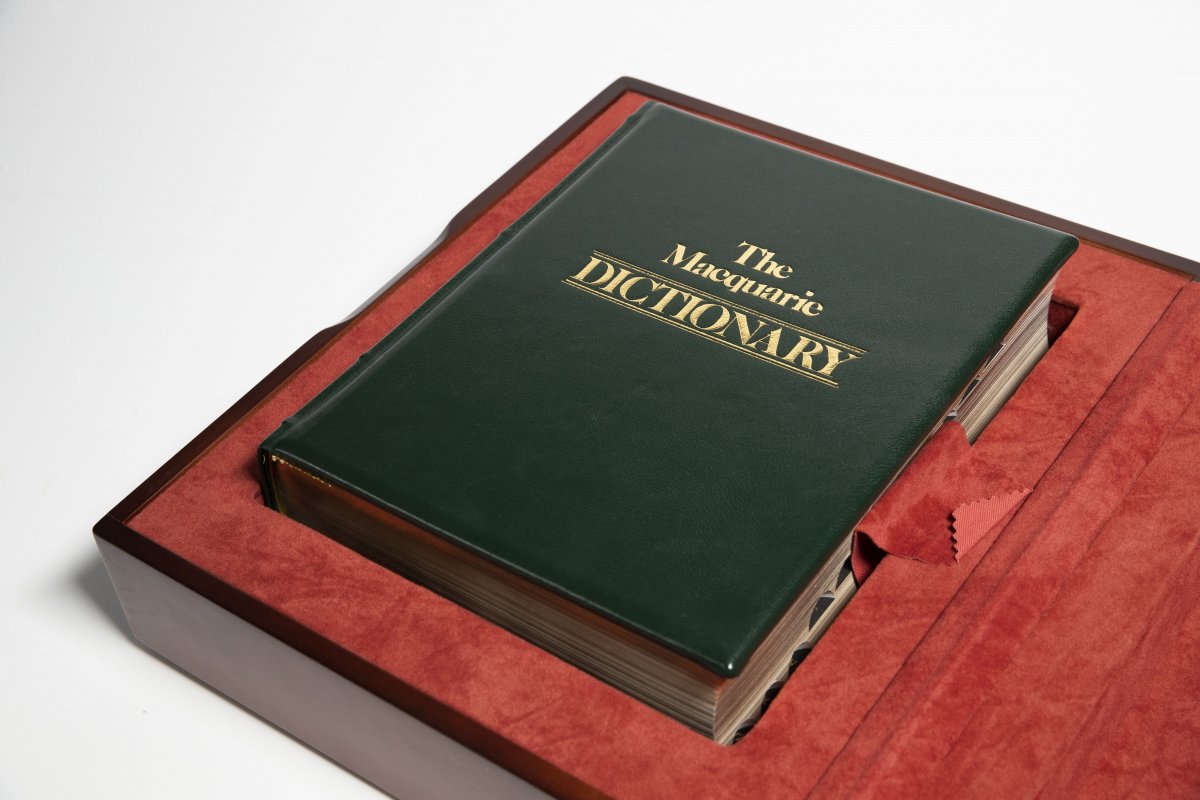

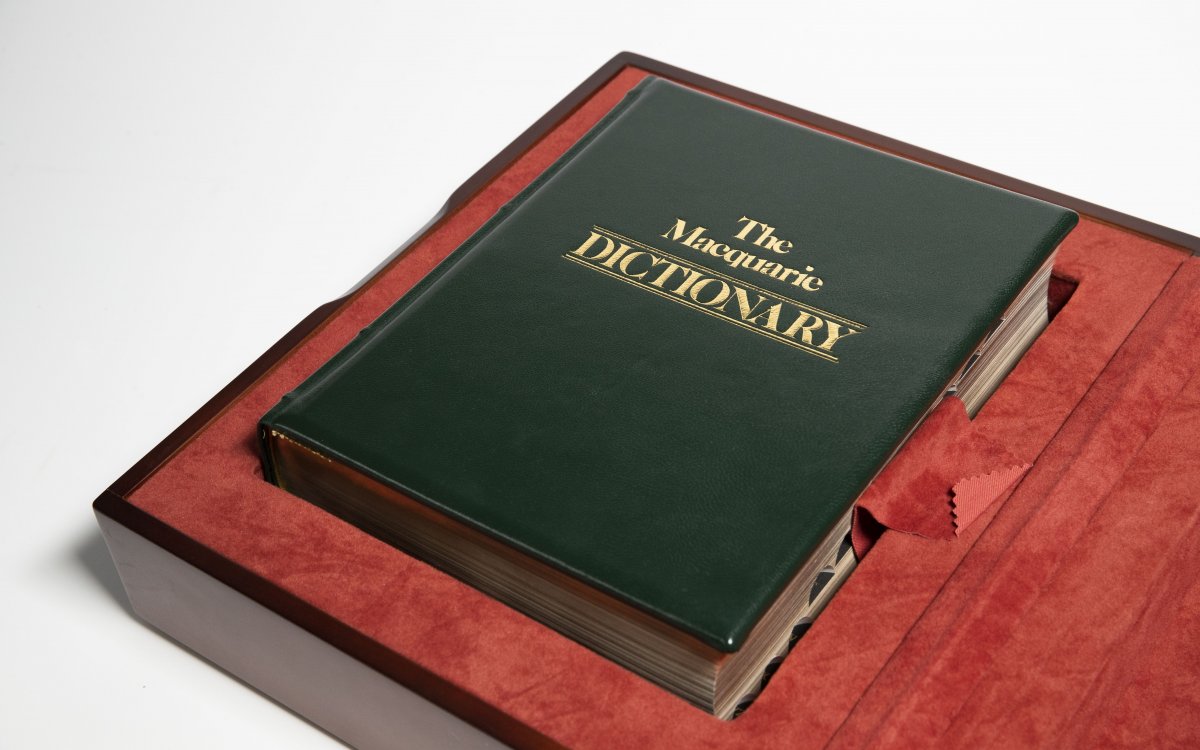

The Macquarie Dictionary was Australia’s first major dictionary project and was first published in 1981. We have two first editions of The Macquarie Dictionary from the 750 signed and numbered copies, one in a special box.

Essential reference or a time capsule, big or small, our dictionaries are an important part of our collections. Within their covers – all, I’m happy to say free from blue contact paper – are languages and specialist subjects from the past and present. They open doors that can only be instructive, even if only for baking.

For more information about our dictionaries, search our catalogue.

Dr Susannah Helman is Rare Books and Music Curator at the National Library of Australia.